It’s a tale of dashed hopes and silver linings. In other words, it’s a typical Irish story. On March 17, 3Below Theaters & Lounge stages the U.S. debut of a play about a small Irish town and a fateful visit from former President Bill Clinton.

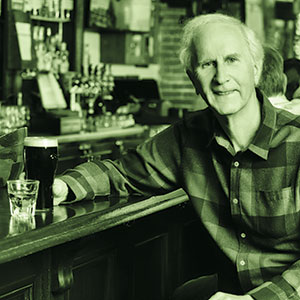

San Jose denizens will recognize the playwright, Tom McEnery, who served as mayor from 1983 to 1991. In addition to the many properties his family company owns downtown, his name is emblazoned upon the city’s convention center.

A Statue for Ballybunion, opening March 17, centers around a short detour Clinton once madein 1998, on his way back to Shannon Airportto the one-street town of Ballybunion in County Kerry.

McEnery is intimately familiar with the story and the milieu surrounding it. In real life, the pub where it takes place is owned by his cousin. McEnery’s play has already been staged in Dublin, at the O’Reilly Theater on Great Denmark Streetwhere the Abbey Theater performs when their facilities need repair. The O’Reilly production came after Ballybunion was performed at writer John B. Keane’s celebrated pub in Listowel. That’s when a producer came to ask McEnery if he wanted to stage the production in Ireland’s capital city.

“I thought a friend had paid him money to put him up to it,” McEnery cracks, remembering the moment.

As directed by Paul Meade in 2017, A Statue for Ballybunion received cordial reviews during its Dublin run. McEnery and director John McGluggage, formerly of the San Jose Rep, hope for some applause here during this weekend of Irish appreciation. The play will have its American debut in the theater at which McEnery cut the ribbon in 1984, back when it was named Camera 3.

McCluggage, well-known from his days with the Rep, says of McEnery’s work, “The characters are so real. I know he says they’re based on real people, but he’s crafted it. When you have crafted characters, you have something the actors can play, instead of just standing there and telling the story.”

BACKROOM DEALS

McCluggage, McEnery and I meet in the former mayor’s private office behind O’Flaherty’s Irish Pub on San Pedro Square, passing the bar and ducking behind the bathrooms into a small cubbyhole in the back. There’s a life-sized cardboard standup of Clint Eastwood”Still the best mayor ever,” says McEnery, referring to Eastwood’s two-year term as chief municipal executive of Carmel.

Scattered about the office are the odds and ends a politician keeps. A golden shovel leans in one corner, a souvenir from some successful construction project. There are framed shots of McEnery with celebrities. The old, uneven bricks of the inner office filter the roar of planes over the Mineta airport flight path.

As we enter, McEnery points to a framed quote from Luis Maria Peralta (1759-1851) which hangs over the doorway. Peralta was the early Spanish official who once owned almost 45,000 acres of Northern California. He lived in San Jose’s oldest house, the Peralta Adobe, still standing just a few doors down in the courtyard of the San Pedro Square Market.

The words, which came late in his life, are a warning to his children, whom he implored not to chase gold in the Sierras. Rather, he advised them to farm and raise livestock.

“These be your best gold fields,” the quotation reads, “for all must eat while they live.”

The quote has a sting to it. So much of San Jose’s modern wealth has been made by and invested in paving over some of the best farmland in the world.

On the subject of sage advice, McEnery says that one of the South Bay’s best-known artists, playwright Luis Valdez, advised him to write plays: “Luis said to me, after his Frida Kahlo movie collapsed, ‘If you do a play, somehow it’ll have a life. Might be 20 people watching it, or maybe it’ll do better than that. But it’ll have a life somehow.'”

McEnery worked and reworked the material of this Irish play. It went from short story to screenplay to staged play. He’d previously staged another production, titled Justice, about California’s last lynching, which occured in 1933 in St. James Park. It’s been the subject of three theatrical moviesone, the heavily fictionalized but brilliant Fury by Fritz Lang. McEnery owns the film rights to Harry Farrell’s still-definitive history.

CAST IN STONE

It makes sense that McEnery would take up the subject of a controversial statue, given the troubles he had with the expensive equestrian statue of Thomas Fallonthe Irish-born settler who served as San Jose’s 10th mayor. (My great grandmother was a Fallon from County Corkhe could be a relative for all I know.) The result was a good, old-fashioned political kerfuffle ending in the replacement of said statue with Robert Graham’s immortal symphony in cast stone, the coiled Quetzalcoatl in Plaza de Cesar Chavez. The latter statue is now the subject of a thousand jokes, like the one about Clifford the Big Red Dog leaving a token of his visit. Public art is always trouble.

The meat of A Statue for Ballybunion is that Clintona contemporary of McEnery’s, born just one year after the former mayorneeded a little hejira right around August 1998, just as Monica Lewinsky was making her deal with Ken Starr. A good thing about Ireland is that it’s far from Washington, D.C. Clinton’s travel to Ireland is described by McCluggage as having “an ulterior motive.” Clinton’s own woes with his upcoming impeachment give this play a contemporary hook.

Though the play certainly takes artistic licenses, McEnery is well-versed in the source material.

“It’s set in a place I’ve been going to for years,” he says. “My grandparents came out from that way, in the west of Ireland, in County Kerry. And the play is set in North Kerry. The joke is that every other person you bump into there is either a poet, a short story writer or some other published author. Maurice Walsh, a novelist, best known for The Quiet Man, is from there. So are lots of story writers and playwrights of the 1970s and 1980s. They have a literary festival there.”

The name Ballybunion looks prettier in Irish: “Baile an Bhuinneagnaigh.” Call it what you will, it’s a small town. There are fewer than 1,900 residents, an economy-sized ruined castle, two golf courses and two cold swimming beaches that are divided, male and female; priests once on the headlands to make sure there was no mixed bathing.

“I actually lived in this little town for four months right after I graduated from college,” McEnery says. During breaks from school, he spent time with his great aunt, before returning and continuing his studies back in America. “My father sent me a letter, are you coming back? Are you ever going to get a job?”

THE TROUBLES

Clinton arrived in 1998, in part to formally recognize the end of the Northern Ireland conflict, or The Troubles.

“Clinton played a significant part in it,” McEnery says. “He was the first president really interested in Ireland.”

The then-president had no Irish ancestry. But even though Kennedy and Reagan flaunted their shamrock-green roots, they never got tangled up in the political mess there.

The partitioning of Ireland was a problem from hell. In the 1920s the Irish fought a civil war over the deal that later-president Eamon de Valera signed with the British. In exchange for independence, de Valera ceded six northern counties to Great Britain. This was popular with Irish Protestants, unionists who looked to England as the motherland and who swore there’d be no surrender.

The IRA, who took to their guns to get the British out, sang forbidden lyrics to the tune of “Off to Dublin in the Green,” as the Catholic former MP from Northern Ireland Bernadette Devlin wrote in her autobiography:

“Some folk fight for silver/

and others fight for gold/

but the IRA are fighting for/

the land de Valera sold.”

(The Irish are great singers but not great lyric writers, Devlin added.)

Decades of wanton cruelty and urban guerrillaism came to a halt on Good Friday, April 10, 1998, when both sides agreed to a power-sharing treaty.

“Clinton came to bless the agreement signed by the British and Irish Prime Ministers, ending those years of strife we all read about in the papers,” McEnery says. “So the people in Ballybunion decided that getting Clinton there would be a tourist draw. In Ireland, every time the tourism lapses, some sort of a miracle would happen … such as a statue of the Virgin Mary coming to life: She’s walking again!”

McEnery wasn’t there the day Clinton buzzed through town, but he was there the day afterward. He insists the events are all true.

“The statue was built, and the statue doesn’t arrive on time,” he says. “Clinton did come to play golf. They’ve already sold the Uncle Sam hats for a half a pound each to all these people who had come to this pub to see Clinton. When I was mayor, occasionally a president would come to town. If you’d ask them if they could alter their schedule and come over for 5 minutes, you might as well be asking for a Papal edict. No way they alter anything.”

McEnery decided to weave the tale of the world’s first statue of Bill Clinton, with a story of the publican Jackie. His beloved daughter may be soon following the well-worn road out of Ireland, after she meets a good looking American from San Jose. McEnery says, “she has the Irish conflictdo you go or do you stay? Millions go.”

A Statue for Ballybunion runs for five performances. Opening night is currently sold out.

“I do have a lot of family members,” McEnery says.

He’s thrilled to have it performed in San Jose at last.

“No matter where you live, you have a feeling of kinship or affinitylove might or might not be too strong a word,” he says, referring to San Jose. “You don’t want other people criticizing the place. My grandmother didn’t come to San Jose to work as a domestic because it was really a good way forwardshe came like everybody comes these days. They come to America or to Europe from the Southern Hemisphere … there was a better chance in America than in Ireland. In Ireland there’s a great love of the country, yet the Irish go to the four corners of the world and have pretty good success. But that twitch on the thread always brings them back home.”

A Statue for Ballybunion

Mar 17-22

3Below Theaters & Lounge, San Jose

3belowtheaters.com