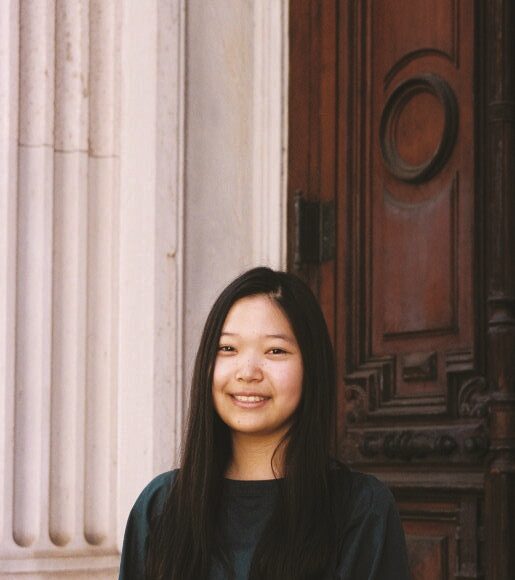

Bestiary, the startling first novel by K-Ming Chang, took place in Montebello, the Southern California city where much of her family originates. Now based full-time in San Jose, Chang has relocated her storytelling geography with her.

“My work is increasingly moving up to San Jose,” she reflects, “and that mimics the journey of my family.”

Chang’s paternal grandmother has lived in San Jose since the 1980s. As a child, Chang would often visit her townhome, greeting the neighbors.

“When I think of San Jose,” the author shares, “I recall these very intimate domestic spaces of my elder family members: specific kitchens, specific yards where I spent time envisioning stories.” One hideaway where she passed hours in reverie: an “amazing little cupboard” tucked under her grandmother’s staircase.

This week, Chang’s newest collection Gods of Want is out via One World/Random House. The release comes as San Jose itself becomes more a part of her writing process.

“Now that I’m an adult, I’m finally exploring the city and understanding the scope of it,” she says. Brief childhood jaunts to Raging Waters once felt “like a lunar expedition,” leaving her wide-eyed. “Everything was larger than life,” she marvels. “I remember thinking, oh my God, this place is on Mars.”

Due to its rapid change, today’s San Jose continues to defamiliarize.

“Everyone here is really hustling,” she observes. At public libraries, she can slow down her pace. In the still, air-conditioned environment, she loses herself for hours, surrounded by patrons absorbed in their own quiet undertakings.

She notices, too, how wildlife exists alongside humans here. Lately she’s been spellbound by local birds, thanks to free field trips with the Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society.

“I’ve been wanting to write about crows,” she shares. “On trash day, I’ll see them trying to open garbage cans. [They’re] such characters of this city.”

San Jose, Chang has noticed, is also rife with stories about migration and the past. “Multi-generational families have a really strong presence,” she observes. So, too, does “the persistence of history-making and place-making, something that is global and part of the diaspora too.”

A particular focus of Chang’s work is matrilineal storytelling (the first section of her new collection is called “Mothers”).

“The women in my family and neighborhood have always tied me to place,” she says. “There is this inheritance of story, memory, language and intergenerational knowledge. The voices of women are constantly accompanying me or haunting me in some way. I’m always in conversation with them and carry them with me.”

While personal history informs Chang’s work, it is more lore than memoir. She is a self-professed “huge fan” of the inauthentic, the made-up and the artifice of storytelling.

“That to me is the most pleasurable part,” she says: the maximalism that myth can allow, as well as the contrast it affords. “[Lore] can be so huge, like the creation or disruption of worlds. Or, on a micro level, it can just be about an individual. I love how it holds all those things.”

Chang’s lush prose is full of decadent-but-icky imagery. Grotesqueries abound in her work, from bones that sing when broken to dogs who defecate maggots. The grotesque, she reflects, both attracts and repels, and these sensations may feel similar in our bodies. “I love the idea that everything and its opposite are a lot closer and more synonymous than we think,” she explains.

A simple, everyday example: teeth. In her new work, the word teeth appears 62 times across stories, whereas tooth, molar and dentist appear 16, 15 and 11 times respectively. “I’m always waiting for people to notice that,” Chang remarks. “There’s so many teeth all the time. I’m like, oh wow, this is continuing. This is a threat.”

Teeth, she says, are creepy. They fall out in anxiety dreams. A horror-enthusiast, she emphasizes that they are symbols of consumption, desire, hunger—and status. “When I was a kid,” she shares, “my mom would always remind me: ‘your teeth are the most expensive part of you, so be careful.’ I internalize the idea that teeth must serve you for the rest of your life.”