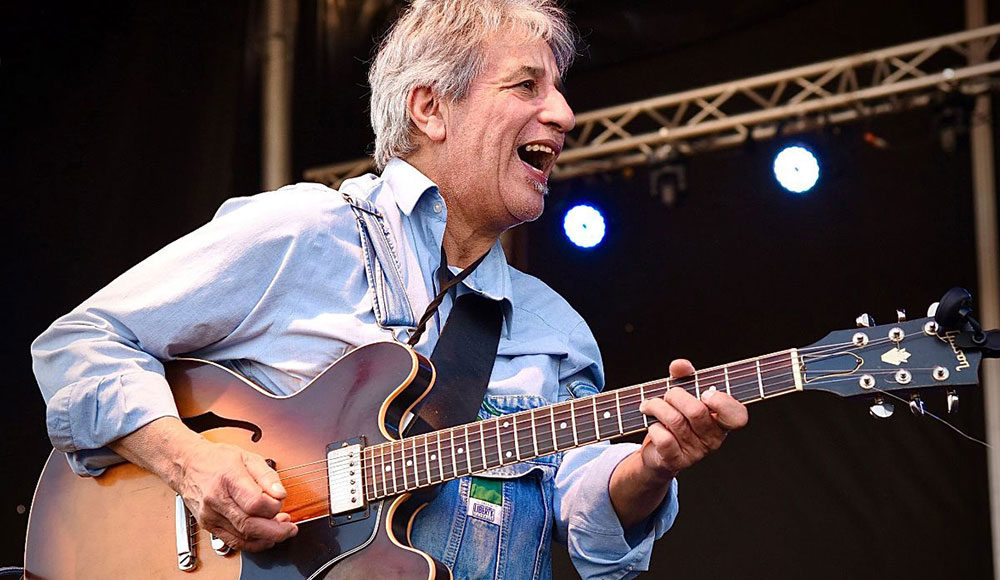

Chris Cain is a star in the blues world. The electric guitarist, singer and songwriter has just released Good Intentions Gone Bad, his 17th album and second for prestigious blues label Alligator Records.

Cain’s expressive style communicates a deep love and understanding of the classic blues form, while his lyrics and delivery imbue the original music with a here-and-now character. He’s on tour in Italy this month, promoting the album, and will next return to the South Bay for an Aug. 7 show at Jazz on the Plazz in Los Gatos.

Cain’s family roots extend to Memphis, Tennessee, but he grew up—and paid his musical dues—in and around San Jose. He saw, heard and rubbed shoulders with guitar legends whose work would inform his own music. “I was lucky,” he says. “Back then, San Jose had a lot of clubs where those guys you’d dig on records would play.” Cain was able to catch live sets by blues and rock legends like Mike Bloomfield. “On any given weekend,” he says, “you could go see somebody like Elvin Bishop … for 50 cents!”

As a teen, Cain yearned to visit the Bodega, situated at the site now occupied by the Water Tower II Plaza. “Albert King would play for three nights in a row,” he recalls. Unfortunately, Cain wasn’t old enough to gain admittance to the club. “So I would just stand near the biggest door and listen,” he says. “But there were guys there who I knew; [sometimes] they would open up the side door and just pull me in!”

And that local scene had room for young local players, too. “It wasn’t like being in New York or somewhere,” he explains. “There was a scene: we had places where even if you didn’t have a band, you could play with other guys, get your own thing together.”

At that point, Cain’s musical worldview was completely centered on blues. “I had no idea about song form beyond the twelve-bar format,” he admits. “I wasn’t familiar with R&B; I was too busy—locked in my room with my B.B. King records. That’s why I didn’t have a date until I was 30!”

Soon enough, Cain earned an early opportunity that broadened his horizons and set him on his musical path. Keyboardist Clifford Coulter was Bill Withers’ musical director, and between tours he played gigs of his own. Long before the advent of MIDI technology, Coulter made use of backing tracks to create a full band sound without a stage full of musicians. But he hired Cain as a guitarist for his multi-genre set. “There was nothing he couldn’t play,” Cain says. “He’d say, ‘Get your jazz tone ready.’ And next, there’d be some funk thing.”

The tape-backing format meant that when it came time to solo, Cain had tightly regimented sonic spaces in which to peel off a lead break. “You had to be ready,” he says. “Working with Clifford, I think I learned more about playing the guitar than anywhere else,” he says. Coulter passed away in 2021. “I miss him so much,” Cain says.

Back in the San Jose of those days, “there were gentlemen [players] who would take the time to show my poor little patootie something,” Cain says. “Today, there aren’t as many clubs where you can go play the blues. You go to a jam night, and that guy’s got an agenda; he doesn’t want you to really shine.” So Cain tries to carry on that tradition of encouraging younger players today.

Cain is developing another tradition: Good Intentions Gone Bad marks at least the fourth time he has worked with Christoffer “Kid” Andersen of Greaseland Studio. The multiple Blues Music Award nominee has built a well-earned reputation as the go-to producer for many of today’s hottest blues artists. “Kid has a gift,” Cain says. “He makes it possible for me to see what I hear in my head.” He says that Andersen is the sort of producer who “wants you to get what you want, and he knows when you’re getting it.”

Andersen works quickly, a sought-after quality for budget-minded recording artists. “There’s some guys who take two days to get a drum sound,” Cain says. “But him? Bing! Immediately. And you’re ready to go. He really is a gift to this particular music, and to the planet.”

Cain considers himself lucky to have made his string of highly regarded albums. And among the many things he has learned along the way, one stands above the rest. “I’ve learned a lot about playing with other guys,” he says. “Because if I was gonna have my own band, I had to learn how to get my vision without making anybody mad.”