In 1905, Henri Matisse painted wife Amélie in Femme au chapeau (Woman with a Hat). The tip of her nose is lemon yellow, the nostrils and bridge a mixture of grays and greens. Her face, hat and dress all form a riot of different colors that somehow coheres into a portrait.

Knowing the outline of her husband’s career and little else about her biography, her gaze out of the painting, which is hanging at SFMOMA, always stops me in my tracks.

Portraiture routinely fails to capture human proportions accurately—Amélie’s eyes are asymmetrical, and her chin is squared off at an odd, perfectly inhuman angle. But Matisse suggests her personality, his perception of her and the world they inhabit as a couple. One that exists beyond the edges of the canvas. As the central figure of a colorful fantasia, Amélie enters the territory of myth. As such, the painting is allusive and lends itself to as many interpretations as the number of shades and tints and hues contained within it.

The portraits in the Livien Yin: Thirsty exhibit at Cantor Arts Center exist in the 21st century’s aftermath of such classical portraiture, comfortable companions to high-art graphic novels. Yin’s color palette, like Matisse, veers toward the fictional. The storytelling is imagined across a muted field of dreamy technicolors.

In Thirsty No. 1, rivulets of water drip down the subject’s face, gliding down onto the Mandarin-collared shirt in distinctive yellow, green and blue ribbons. The water itself, contained in a tilted glass or mason jar, is even more dynamic. Oranges, blues, pinks and browns slosh about reflecting the environment of the room and the painter’s state of mind.

Yin, a 2019 graduate of Stanford’s MFA program, doesn’t include thought or speech bubbles within their canvases. The subjects all project their unspoken emotions to the viewer subtly and directly, the way that actors do. But the captions are directly adjacent to them in the boxes of explanatory text.

Two women were already on a docent tour when I walked into the white-walled gallery (the lighting is too bright and should be dimmed or softened). The docent had the inside scoop on all things Livien Yin. She also sounded like an acquaintance of the painter, or at least someone who runs in the same circles. She knew, for instance, who the model was in the 2022 painting All You Can Ache and where it was set. Whatever her companion thought or felt about the work and the mini-lecture was largely communicated in the affirmative, as both physical nods and short exclamations.

Feeling hemmed in by all of the factual information, I moved to the other side of the gallery in order to free up my own personal set of associations and interpretations.

Reading Yin’s biography and the curatorial overlay are certainly relevant. They provide the painter’s origin story and the historical and cultural contexts that have informed their art practice. But they also feel prescriptive, a declarative statement: “There’s only one way to look at and understand Yin’s paintings and this is it.”

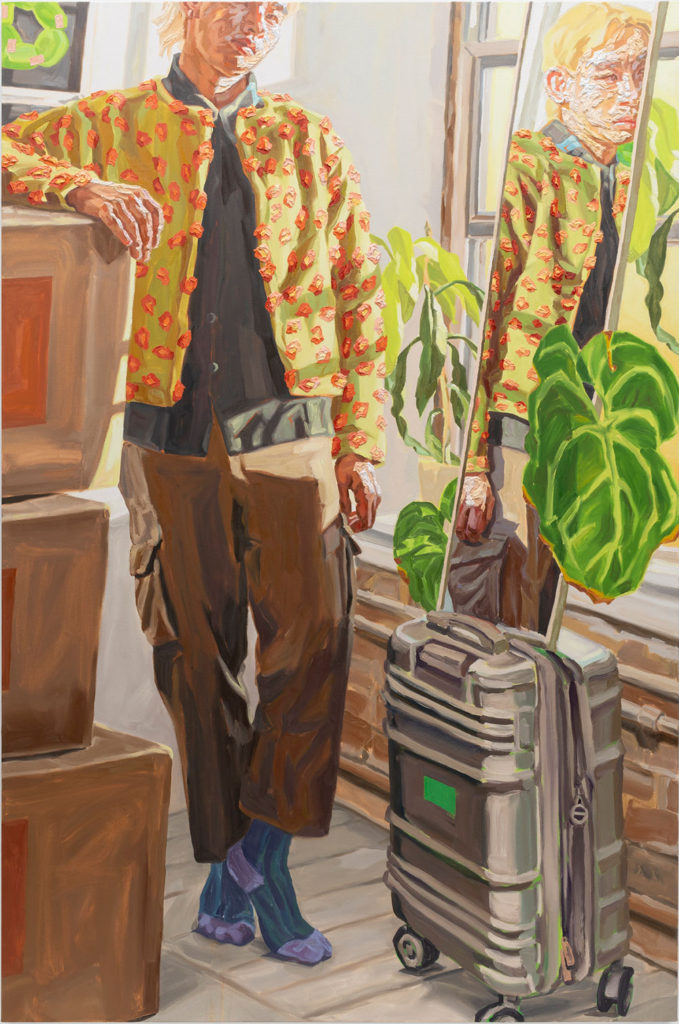

In addition to Yin’s unification of cross-generational Asian Americans (no small feat), I was struck by the lava-like fluidity which informed the motion of their brush strokes. Several of the paintings are encrusted with thick layers of impasto. The figure in The Comma Between looks directly at the viewer but their reflection also appears in a slim, floor-length mirror.

Essentially, the artist creates two portraits in one, a divided self. The subject’s “real” face, painted in an array of shadowy flesh tones, is cropped at the temple, the right eye and ear are slashed in half. The mirror reflects back a second narrative. The left side of the face is sculptural with strips of whites and beiges affixed on the skin like so many pieces of torn-up papier-mâché.

The Comma Between’s wall text explains that the person in the portrait is struggling with the idea of home. But that should act as a point of departure for the viewer. Perhaps that’s the subject’s primary internal conflict, but surely it’s not the only one.

There’s also a lively correspondence between the impastoed face and the decorative red elements, possibly flowers, on the figure’s chartreuse jacket. The flowers look like they’re so loosely stitched onto the fabric they might float down to the floor in a sudden draft of wind. The troubled layer of patchy second skin might also be a temporary affliction, if a panacea for psychic distress one day presents itself.

Livien Yin: Thirsty is now on view at the Cantor Arts Center through Feb. 2, 2025. 328 Lomita Drive at Museum Way, Stanford. museum.stanford.edu.