![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

A few good books add depth to a shallow year

By Michael S. Gant

THE TV SCREEN brings us flat close-ups of the man in the hole, who turns out to have been no more powerful than the man behind the curtain in Oz--his vials of anthrax, a bottle of Dove moisturizing shampoo; his Emerald Empire, a chimera composed of our own projected fears. The newspapers add some dimension to the flickering 2-D tableaux on the tube, but for any real depth, it helps to dig into the past with a few good books.

Reading backward through the decades and even centuries serves two purposes, depending on one's mood after scanning the morning headlines: (1.) The consolation of context; after all, we've lived through harder times than these. (2.) Pure escapism; things really were better in the good old days, so why not retreat into the past?

Two notable fictions of 2003 function as de facto chronicles of Silicon Valley (a chimerical land in which 10 years equals an eon). Local cyberpunker and futurist Rudy Rucker's The Hacker and the Ants, originally published in 1994 and rereleased as Version 2.0 (Four Walls Eight Windows; $13.95) with some updates, creates a clever parallel universe centered on Los Perros (read: Los Gatos). Rucker skewers the dreams of the early dotcom craze as virtual ants invade the hero's computer, creating a virus that destroys all the TVs in America. Dystopia or utopia? You decide.

Another history thinly disguised as fiction jumps back 10 years to 1984--George Orwell's annus horribilus and the year the famous Apple fight-the-power TV spot ran. In Ellen Ullman's philosophical thriller The Bug (Nan A. Talese; $23.95), a programming genius wrestles with an impish computer virus that functions as an astute metaphor for all our failures to achieve perfection--in computer code, in human relations and even in geopolitics.

The anti-coffee-table book of the year, photographer Michael Light's large-format volume 100 Suns (Knopf; $45), presents a repellent yet weirdly compelling collection of photos of American A- and H-bomb tests from the not-so-dim past, circa 1945 to 1962.

Light has rephotographed and, in some cases, recropped and digitally altered declassified military prints, creating startling glimpses of mushroom clouds and some of the world's most toxic sunsets. In one distorting shot that unintentionally parodies posters for '60s surf movies, soldiers on a tropical island are silhouetted against the glow of a distant explosion--it's Beach Blanket Apocalypse. The book is a chilling rebuke to the Bush administration and its renewed fascination with tactical nukes.

In 2003, Nobel novelist Gabriel García Márquez turned from fiction to fact. In Living to Tell the Tale (translated by Edith Grossman; Knopf; $26.95), the first installment of a three-part memoir, the famed Colombian magical realist meanders through his upbringing and early days as a reluctant law student, novice journalist and nascent novelist. In his beautifully detailed anecdotes about his philandering pharmacist father, persevering mother and horde of siblings, García Márquez displays, as if on a crowded specimen table, the raw material from which One Hundred Years of Solitude was assembled.

Even in this faraway land, which might as well be Oz to an American reader, politics intrude. In one of the finest sequences in the book, García Márquez describes the riots that swept Bogota in 1948 after the assassination of a famous Liberal party leader. The martyr's name is unfamiliar but not that of the young Cuban student who had an appointment with him that afternoon: Fidel Castro.

Just over a century ago, the Bay Area was caught in the grip of a medical panic that presaged the SARS outbreak that spooked so many travelers earlier this year. Marilyn Chase's The Barbary Plague (Random House; $25.95) recounts an outburst of bubonic plaque transmitted by hitchhiking fleas on ship-going rats. Because the ships came from the East and felled their first victims in San Francisco's Chinatown, nervous politicians insisted on a blanket quarantine of the district. This approach, fueled by decades of anti-Chinese sentiment, led to a refusal by Chinatown's citizens to cooperate with doctors--a cautionary lesson for public health to this day.

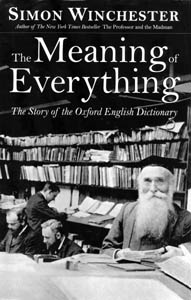

The constant in the year's best books (even in translation) is an attention to the supple beauties of the English language--a vast expressive engine preserved in all its glory in the Oxford English Dictionary. The creation of that monumental lexicon is recounted with a deft hand by Simon Winchester in The Meaning of Everything ($25; Oxford University Press).

Winchester, a master of the discursive footnote (located where it belongs, at the bottom of the page, not relegated to the back matter), deftly parses both the eccentricities of early compiler Frederick Furnivall, whose interest in athletic young ladies diverted him from the task at hand, and the heroic dedication of James H. Murray, who toiled 50 years on the great task of tracing the history of the language through the writings of its practitioners.

But the dictionary doesn't help without some principles by which to apply its extravagance of choices. This year also saw the publication of the 15th edition of The Chicago Manual of Style ($45; University of Chicago), an indispensable set of rules and suggestions for building sentences and pages into consistent, coherent publications. In a world that seems determined to embrace chaos at every turn, even a style manual offers a welcome semblance of order--a constitution for the language worth defending.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Paging Through Oz

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the January 1-7, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.