Christopher Gardner

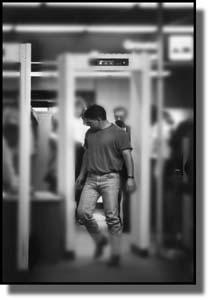

X-ray Division: At the heart of the pre-board screener debate is how much human discretion is needed to interpret the data of machines.

To keep costs down, the airlines have decided to pay entry-level wages to the people who check for guns and bombs on commercial flights. But, relax. They only find one weapon a day.

By Michael Learmonth

AS THOUSANDS OF TRAVELERS and their carry-on luggage were herded through airport security checkpoints this holiday season, many could find solace in the knowledge that, statistically, air travel remains the safest form of mass transit ever devised. Uneasy fliers could, while trying to forget images of the TWA and ValuJet catastrophes, remind themselves firmly that more Americans were killed in the last three months in auto accidents than in the entire 60-year history of commercial aviation. Despite the recent terror in Ethiopia, hijackings in this country are a thing of the past. The last bombing on an American airline was on Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988.

They could also take comfort in the fact that today, American airports are patrolled by police officers, Federal Aviation Administration agents, the FBI, even United States Air Marshals who pose as passengers, patrolling for terrorists and trained to shoot-to-kill.

But probably best left out of their pre-boarding meditations would be the little-known fact that there remains a weak link in the system which is currently keeping some airline safety experts awake at night. Despite the Mission: Impossible intrigue of its upper ranks, the linchpin of the security system are the airport's lowest-paid, least-trained workers, called "pre-board screeners." These are the people who operate the X-ray machines and metal detectors and sometimes search the luggage and clothes of passengers in an effort to keep bombs and weapons out of the airplane. Around the country, they make about $5 an hour. At San Jose International, in the middle of one of the highest cost-of-living areas in nation, screeners start at $4.75 an hour, with no benefits.

"You get what you pay for," says Jane Iverson, who supervises the screeners at San Jose International. "I find it appalling what we pay these people."

But Ralph Tonseth, director of aviation at San Jose airport, argues the system was designed for just such workers. "The job has been designated an entry-level job," he says. "The machines do most of the work. They just have to interpret and I think they do that adequately."

AS IT TURNS out, airports and airlines share responsibility for the safety of the commercial air travel. Typically, airports contract with a law enforcement agency to provide police protection. San Jose International, for example, is patrolled by a division of the San Jose Police Department and takes responsibility for securing the building and providing security equipment such as X-rays and metal detectors. But security of the sensitive gate areas are the responsibility of the airlines. This, the airlines contract out to the lowest bidding private security firm, which could be Ogden, Wackenhut, or the low bidder at San Jose's airport, International Toll Services.

In the wake of the TWA Flight 800 disaster President Clinton appointed Vice President Gore to chair the newly formed White House Commission on Aviation and Security. Three of the commission's 20 preliminary recommendations address the issue of pre-board screeners. The commission wants to start requiring background and FBI fingerprint checks, to regulate the companies that hire and train screeners, and to increase testing of the security gates with armed decoys. The Gore commission will issue a final report on Feb. 2.

Currently, the FAA only requires that screeners have a high school diploma, a GED or equivalent "education and experience." They require screeners be able to respond to "the spoken voice and audible alarms generated by screening equipment" and to distinguish between colors on the X-ray screen. They also must be able to give English instructions to passengers, read identification cards and airline tickets, and write incident reports.

Test Your Metal: Aviation officials say the low pay and minimal training of pre-board screeners has not kept pace with the stepped-up security needs of most airports.

Photo by Christopher Gardner

INTERNATIONAL TOLL Services is the private company with the contract to provide pre-board screeners at San Jose International. Their office is located in a tiny, 10-foot-square room near the Delta Airlines counter in Terminal C. Faded blue and gray uniforms are stacked along the back wall. Inside, there is a desk, computer, phone and printer. The manager, Jane Iverson, is responsible for hiring, training and staffing of the screening checkpoints and for ramp personnel for Delta Airlines.

"People show up and quit," Iverson says. And while high attrition might be expected among minimum wagers at a fast-food franchise, security gates are especially sensitive. "It's obvious to me we have to do something for these people. They are paid the lowest wages in the airport."

Applicants for pre-board screener positions must agree to a drug test and 10-year background check. They are given a 12-hour training course to learn to use the equipment. On the job, the screeners are tested by the FAA. A failed test results in a fine for the airline and dismissal of the screener. The top salary a screener can earn is $5.15.

"It's the most important job here besides flying the airplanes," contends Iverson, who hopes the Gore commission recommendations will result in increased wages for her workers. "I can't bring in new people at the rate we are required to pay."

When the screeners detect a weapon or other contraband at San Jose International, they detain the passenger and hit a silent alarm for the airport police. "We respond on a daily basis to a handgun or other dangerous weapon at the security checkpoints," said Lt. Luca. "Those are the success stories. Do I think that individuals with weapons get through the checkpoint? I think so. Is it often? No. The only way to make it completely safe is to close it."

I REMEMBER when I first noticed the airport gate shakedown getting more intense. It was soon after the bombings in Oklahoma City and the World Trade Center. The lines got longer at the gates. Passengers who tripped an alarm were thoroughly scanned with the metal detector and patted down. Flying out of Oakland International Airport once, I was taken aside with some bewildered and annoyed business travelers and asked to boot my Powerbook. It had been on the fritz of late and I thought there was a good chance the battery was dead anyway. Fortunately, the "Happy Mac" icon came up. The screener said I was free to go.

The FAA determines security for the nation's airports on a scale from 1 to 4 called the "Aviation Security Level." In August 1995, the level was raised from 2 to 3. The FAA doesn't disclose the measures involved for each of the four security levels, or the reason for a change, though a spokesman for the Air Transportation Association of America said the laptop check was influenced by the bomb hidden in a Toshiba portable radio that brought down Pan Am 103.

As I waited for my plane to board I remembered there was only one battery in my Powerbook. There are compartments for two. Couldn't a bomb be hidden there?

"A sophisticated terrorist would not be caught," admitted Tim Forte, a retired FAA and National Transportation Safety Board agent. Forte, who now teaches at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Fla., said, however, the screener would most likely have caught an "Oklahoma City kind of group," notorious for sloppy work.

"Accidents serve as catalysts for change in the system," said David A. Fuscus of the Air Transport Association of America, which represents most major airlines and some airline security contractors. After Oklahoma City, airport parking enforcement intensified, especially in the pick-up and drop-off zones, to prevent the type of bombing the blew the face off the Oklahoma City Federal Building.

THE COSTS OF security are borne almost entirely by the airlines and airports, and are passed on to passengers in the form of higher ticket prices. So far, San Francisco International is the only Bay Area airport equipped with a million-dollar CTS 5000, the newest technology in baggage X-ray that can detect plastic explosives.

While the Gore commission recommends raising the qualifications of pre-board screeners, the airline industry argues it shouldn't have to pay the entire bill. "We are making the argument that terrorism is a national security issue," Fuscus said. "It should be paid for by the federal government."

Because they receive so much press, airline accidents cause national soul-searching. Despite the squawkings of Internet conspiracy theorists, there is no evidence the two major disasters last year--TWA and ValuJet--had anything to do with terrorism. But graphic pictures and harrowing accounts of the hijacking of an Ethiopian Airlines jet that ended in an ocean landing and 127 corpses resonates deeply with Americans, who account for 90 percent of the world's air travelers. Ironically, said Forte, had the airline been American, a U.S. Air Marshal would have likely been aboard.

New security measures are usually implemented to anticipate future danger. "You have to stay ahead of the curve," said Susan Black Olson, an Airports Council International spokesperson. The industry and air travelers share legitimate fears for the future. What if the nation's airports became targets of McVeigh-type wackos? What about the sophisticated terrorist willing to die to make a point? There are no sure-fire answers. Just a security system that evolves and improves.

The wages, training and working conditions of screeners will be at the heart of the evolution. A minimum-wage pre-board screener is more susceptible to bribes than a better-paid, more professional guard would be. The repetitiveness of their work could make even the most conscientious screener slip up. As technology advances, so do the tools at the disposal of security, and the potential criminals. In the end, we put an incredible amount of faith in the people on the front lines of the system. The screeners.

"Terrorists are pretty damn clever people," said Richard Gritta, an airline security specialist. "Humans remain very, very important."

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)