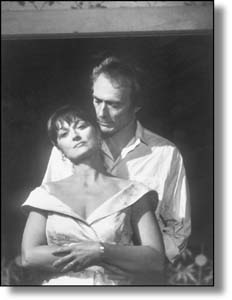

The Adoration of the Eastwood: Meryl Streep in "The Bridges of Madison County," like Richard Schickel in his new biography of Clint Eastwood, seeks salvation in the arms of the ultimate star/filmmaker/icon.

Photo by Ken Regan/Camera 5

Richard Schickel's 'Clint Eastwood' isn't biography--it's hagiography

By Allen Barra

IF LOYALTY in a critic, as Shaw said, is corruption, then Richard Schickel is rotten. Schickel's Clint Eastwood--A Biography clocks in at 537 dense pages, longer than any biography of any filmmaker I own, including a bibliography that lists more books than its subject would seem to have read. There is scarcely a negative word or opinion about Eastwood in the entire volume, or at least not one allowed to stand without having Schickel stamp the heretic as a member of some dark conspiracy.

"There are strangers," writes Schickel, a veteran film critic for Time magazine, "who continue to resent and reject his message." (You get the impression the "his" should have a capital H). Fortunately, the power of the doubters "is now greatly diminished, but it is [still] there, especially in some of the odder corners of academia, and it is not without its murmuring influence."

Schickel has seen all of Eastwood's movies many times, and the experience has purified him of doubt: "I, however, trust the many tales told on the screen over this long career, and I trust the honesty of their teller." Abandon all doubt, ye who enter unto this book.

I picked up Clint Eastwood wondering if it would lead me to an appreciation of an actor and director whose talent I always regarded as modest, and whose range and sensibilities I saw as rather narrow and limited. I finished wondering if I was even worthy of Clint. But who possibly could be?

In the course of the book, he is identified, by himself and others, as "a rebel" (deep in his soul) and a "working-class guy" (albeit one who never held a working-class job for long); a favorite of Reagan and Nixon but also a "die-hard liberal"; a consummate man's man, but also a "feminist filmmaker"; the ultimate action star but at the same time someone who continually subverts the traditional concept of macho; a man whose films display a sensitivity toward blacks, Indians and gays; a director comparable if not superior to John Ford, Woody Allen and, dare we say it?--Schickel doesn't quite dare, but he gets William Goldman to say it for him--Orson Welles!

At a presentation for Eastwood attended by Prince Charles, David Thomson is allowed to observe that "a visitor from another planet, advised on how to recognize modern royalty--its natural eminence, its grace and authority, its sense of divine right made agnostic in simple glamour--would have no doubt which man was the prince." He--or at least his "screen presence"--is "more aura than man."

You get the message: He's a king, he's a prince, he's a queen, he's our sister, he's our daughter, he's the mother of all American cinema. "What is in his soul," writes Schickel, "is in all of our souls ... acting out for himself, he acts out for all of us." I don't know about the rest of you, but I resent any critic pushing Clint Eastwood on me as a soul mate. Daniel Day-Lewis, maybe, and Jim Carrey, certainly, but not Clint Eastwood.

Did I mention that Clint Eastwood is an authorized biography? But then, what other kind would be needed? Since Clint is the reference point for all things, he by definition needs to be the only one quoted on numerous controversies: the women he has left or who have left him, the directors he has fired for not directing a movie enough like Clint Eastwood to suit him. Or on political controversies such as Eastwood's support of an expedition by right-wing nut case James "Bo" Gritz to free supposed MIAs in Laos and Thailand.

Regarding the directors, Philip Kaufman was dismissed by Eastwood during the filming of The Outlaw Josey Wales for "indecision" and "self-indulgence" (defined by Eastwood), and if you didn't know, you'd never find out from Schickel that Kaufman went on to direct Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Right Stuff and The Unbearable Lightness of Being, all of which are regarded by some critics as having more artistic vision in each frame than Eastwood has displayed in his entire career.

The Sondra Locke thing? Clint dismisses it with "How could I have been such a bad judge of character?" That it might be Locke whose judgment was faulty isn't a factor to be considered. One simply needs to trust the honesty of the teller.

Lowered Visor

THERE IS an interesting book to be written on the subject of Clint Eastwood. Has there ever been a superstar with so little talent whose supporters were so willing to accept as a genius? Eastwood's current critical status as demigod has much to do with the fact that no superstar has ever worked harder to ingratiate himself with critics by attending festivals and giving interviews with small film journals.

The film-critic establishment has responded with near-slavish devotion, though to those outside it, as James Wolcott wrote years ago in an oft-quoted Vanity Fair piece, "The truth is not that Eastwood's films have gotten 'hip,' but that the movie critics have gotten so square."

Clint Eastwood really isn't a biography. Eastwood's personal vision, assuming he has one, isn't addressed save for some psychobabble about "Pacific Rim Transcendentalism, a belief that nature in the several majestic aspects that California presents it, is the ultimate source of spiritual renewal."

What the book is is a myth-mongering fan-magazine tome written to punish every "murmuring influence" who has ever rejected Eastwood's "message." For instance, Sergio Leone (who launched Eastwood to fame in the spaghetti Westerns) is trashed for what seems to me to be a perfectly fair comparison of Eastwood and Robert De Niro: "They don't even belong in the same profession. De Niro throws himself into this or that role, putting on a personality the way someone else might put on his coat, ... while Eastwood throws himself into a suit of armor and lowers the visor with a rusty clang."

Schickel's lame response is: "It's exactly that lowered visor which composes his character." How do you argue with someone who thinks a lowered visor composes a character? But of course, it's Eastwood's visor, and that makes all the difference.

The heart of this staggeringly self-deluded book is an all-out assault on the person critic Schickel regards as Eastwood's most murmuring influence, former New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael. Schickel accuses Kael of being "devious," "prissy" and "ineffectively sentimental" for her dislike of, of all things, Dirty Harry.

"Can you imagine that kind of bigotry?" laments Eastwood, mulling over years of bad reviews. "I could," says Schickel, "perhaps better than he." Precisely why Kael's dislike of Eastwood's movies constitutes "bigotry" is something we're not told.

Of course not; it's not bigotry but heresy that Kael is guilty of, and it seems to enrage Schickel that Kael could have the power to undermine his hero's image this way. But it isn't Kael whom Schickel should be confronting but his own hero worship. Better he should have looked at Clint Eastwood in the light of one of Dirty Harry's most famous lines: "A man should know his own limitation."

Clint Eastwood--A Biography by Richard Schickel; Alfred A. Knopf; 537 pages; $26 cloth.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)