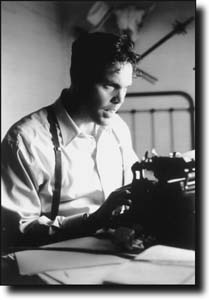

'Weird Tales' stalwart and 'Conan the Barbarian' author Robert E. Howard is profiled in 'The Whole Wide World'

'Weird Tales' stalwart and 'Conan the Barbarian' author Robert E. Howard is profiled in 'The Whole Wide World'

NOT MANY WRITERS across the rift of the WWII world can claim the audiences that H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard have. The former crafted a legacy of strange horrors that filmmakers are still mining. The latter created a vastly popular literature of skulls and spells, huge broadswords and bra-busting heroines, all lorded over by that brawny, long-haired battler Conan the Barbarian--"The goddamndest bastard that ever was," as Howard (Vincent D'Onofrio) describes his hero in the new bio-film The Whole Wide World.

Conan was the first of the sword-and-sorcery heroes. Howard the writer thus fathered an entire genre in a series of short stories written for pulp magazines such as Weird Tales during the early 1930s. Howard the man is remembered in The Whole Wide World, a first-rate romance and one of the most convincing films about a writer's life ever made.

As seen by the unusual woman who loved him, Novalyne Price (Renee Zellweger), Howard is both brash and strangely soft-spoken. The creator of an ur-figure of male supremacy, he was also possessed of such overwhelming devotion to his mother as to arouse comment in any age, Hyperborean or otherwise.

Price knew Howard when she was a young woman. After she retired from her teaching career a few years ago, she published a small-press book about her courtship--and later, friendship--with him. Though they were from small-town Texas, they weren't rubes. Howard was well-read but rough-mannered, given to booming out his "yarns" verbally as he pounded on his typewriter. Price was in the same line of work--only with less success--trying to concoct potboilers for the women's magazines.

The beauty of Zellweger's performance is that she manages to look like she has standards--and would appreciate a more conventional man--without being read by the audience as the disapproving voice of society, a stumbling block to the young artist. While this romance is much different than the one in The African Queen, it's the same surefire cinematic dynamic of a love affair between a man not as wild as he thinks he is mending his behavior to please a woman who is not as tame as she thinks she is.

D'Onofrio's performance ought to make him a star. He displays a soft-bodied machismo (no doubt drawn from his performance as Orson Welles in Tim Burton's Ed Wood) that's attractive, touching, comic and lovable. What if Welles had come from Texas instead of Wisconsin? He might have looked like this, blustering as he has to explain impatiently to Price the purpose of a half-naked girl in a pulp story: "She was dancing the mating dance!"

The caliber of Howard's work is sketched in one joke; it's a gag I first saw in one of avant-garde television comedian Ernie Kovacs' pantomime routines. Kovacs is browsing in a library, and each of the books makes a noise when he opens it: for Camille, for instance, the sound effect is a coughing fit. In The Whole Wide World, Novalyne opens one of Howard's magazines, and from the book issues a Sturm-und-Drang noise of clashing swords, grunts of combat and thundering orchestra, and she has to slam the covers shut in dismay to silence the din.

IT'S ODD how the caliber of an artist's work is less important than the life of the artist, when treated as drama. It might just be that charting the life of the second-tier artist--or filming the second-tier novel--keeps the director from approaching the subject matter on his knees, as the saying goes.

The Whole Wide World could have been a darker tale, and that's because director Dan Ireland has definitely softened Howard's story. One aspect of the writer's life that the movie avoids is the endless pressure of money troubles. On the Web site Robert E. Howard Archives, you can read one of the more emotionally touching things Howard ever wrote, a letter to his editor at Weird Tales, Farnsworth Wright, dated May 6, 1935: "To a poor man, the money he makes is his life's blood, and of late, when I write of Conan's adventures, I have to struggle against the disheartening reflection that if the story is accepted, it may be years before I get paid for it."

Howard goes on to say that times are even worse than usual, talking about his mother's operation, the drought and the dust storms he and his people have faced. Considering how little and how infrequently the pulps paid, you doubt Howard was merely poor-mouthing.

Howard's escape into the world of Conan and his many other bigger-than-life avengers (Agnes de Chastillon to El Borak) was for him what it was for his readers--an escape from the troubles of life. Howard was intoxicated by Conan: "The man Conan seemed to grow up in my mind without much labor on my part, and immediately a stream of stories flowed off my pen--or rather off my typewriter--almost without effort on my part ... for weeks I did nothing but write of the adventures of Conan ... as if the man himself was standing at my shoulder directing my efforts" (quoted by Karl Edward Wagner in the introduction to Conan: Hour of the Dragon, Berkeley Medallion, 1977).

Howard didn't survive. Conan, made of stronger stuff than flesh and blood, did. The Barbarian has been embodied by Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Conan and his various sparring partners have been ripped off for He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. The beguilingly silly, highly Conanesque Xena, Warrior Princess is popular enough to be making way for a new Conan TV show to debut this fall.

But little of Howard's original Conan remains available. Possibly no one since Shakespeare--unless it was H.P. Lovecraft--underwent so much posthumous rewriting and re-editing. Going on a Conan-buying expedition, it was easier to find the work of various other writers about Conan than it was to find Howard himself. I ended up accidentally buying the same novel under two different titles and edited by two different editors: Conan: The Conqueror and Conan: Hour of the Dragon.

Read now, Howard's naiveté is most pronounced in his vague and sometimes comic love scenes. In Hour of the Dragon, Conan has to get moving. The barbarian tells a girl he must leave her behind, although ordinarily he'd ask her to join him. This last clause spellbinds her, and she replies in rapture: "Then my cup of happiness is brimming. ... What you have just said will glorify my life throughout the coming years."

Yes, there are a few howlers in Hour of The Dragon. Conan, about to leap into action, experiences what could only be called a biceps erection: "The great muscles of his right arm swelled in anticipation of murderous blows."

Aside from such lapses as are common to deadline authors (Howard's list of publications would put Joyce Carol Oates to shame), Howard was not a bad writer in the usual ways. He's confident and doesn't overwrite.

The stream of pulp fiction flows, changing its course along the way. The sometimes gross racism of the Conan pulps has been filtered out by new writers, but so has Howard's peculiar force and conviction. The story of Barbarian Princes and Princesses now are smoothed, shored up with anachronism jokes. Ambiguity and irony would have perished in Howard's world faster than a 90-pound weakling.

To Howard, the modern world was too civilized. He wasn't alone in his time: the period between the world wars. From D.H. Lawrence down to much more popular and minor authors, many dwelled on the notion that our citified blood was getting too thin. Protests against how unmanned and unwomened modern people were popped up in the movies, embodied by Jane fleeing the cake-eating blue bloods to go find her Tarzan.

This notion of over-civilization is not one you hear nearly as often now--outside of movie theaters, where some things never change. Howard, dying young, didn't live long enough to see the consequences of the worship of power taken to its extremes in Nazi Germany, nor was he around for the nuclear arms race.

The very quality that makes his work naive has, by contrast, made it endure. Not having lived to see how dire the future was, he was able to make both high-spirited and heartfelt fiction about a barbarian world--precisely because he didn't know about the real possibility of a post-nuclear barbarian Earth to come.

The Whole Wide World (PG; 105 min.), directed by Dan Ireland, written by Michael Scott Myers, based on the book by Novalyne Price Ellis, photographed by Claudio Rocha and starring Vincent D'Onofrio and Renee Zellweger.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)