![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

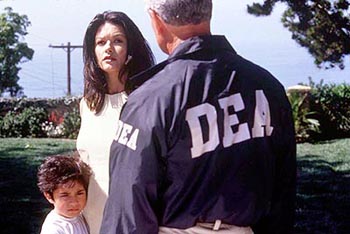

Photograph by Bob Marshak DEA on Arrival: Catherine Zeta-Jones finds herself caught up in the drug war in 'Traffic.' Drug Story Cowboys Steven Soderbergh exposes the war on drugs in the complex 'Traffic' THE CHROME-PLATED giant scorpion is ready to strike! A droplet of some toxic drug oozes from its jointed tail. Fortunately, headphones protect our little animated hero. His thumping music radiates out in concentric rays. Like a sonic blast, the noise blows the hideous metal scorp into pixilated shards. And the moral of the little cartoon story--paid for with a heaping helping of your tax dollars--is that Drugs Are Bad. I've seen this TV commercial 800 mortal times in the last week of idiot-box watching. Here the war on drugs is illustrated in the simplistic vernacular of a PlayStation game. But no one really notices such propaganda; during wartime, disinformation becomes just part of the scenery. Oversimplified, federally funded art like the above gives added importance to Steven Soderbergh's superb new film, Traffic. Here's the first fictional movie in memory to deal with the contradictions and hopelessness of the war against drugs. This war is failing even as it escalates. Like the Vietnam War, it's kept going because it has already cost too much to give up. Based on the British television show Traffik, the film is an exposé disguised as a police story. Traffic shuttles among three different stories, with sidebars. In one section, Manolo (Jacob Vargas) and Javier (Benicio Del Toro) are Tijuana police officers recruited by a hardy old general (Tomas Milian). The old soldier is jockeying for a place as Mexico's head drug warrior. His current assignment is to break up the Obregon brothers' drug cartel, whose trademark is a printed scorpion on the packets of white powder they sell. (The scorpion brand shows just one way anti-drug commercials go wrong. What frightens, tantalizes.) The Mexican scenes, mostly subtitled, concern the difficulty of convincing a grossly underpaid police force to risk their lives to save the Yanquis from their own sweet tooth for drugs. Del Toro, usually a Latin cutthroat in the movies, is a revelation as an honest cop who is betrayed by almost everyone he trusts. But he's still amused by parts of the job. Javier purrs "mi, amorrrrr" at some unfortunates he's arrested. In another rich scene, he tries to keep a straight face dealing with some flustered American tourists who have had their car pinched. Javier is streetwise enough to know where the car is and how it can be ransomed; the Americans, accustomed to a more straightforward flow of justice, don't get the picture and are standing there baffled. Del Toro shows the uses of quietness among angry people. There are times in Traffic when Del Toro is the resurrection of Robert Mitchum. IN SECTION TWO, American DEA cops Montell (Don Cheadle) and Ray (Luis Guzman) are trying to nail the U.S. distributors of the Obregons' dope. Thus they entrap a middleweight dealer named Eduardo (Miguel Ferrer, hugely amusing and as acrid as vinegar). The plan is to squeeze Eduardo into turning against his boss Carlos Alaya (Steven Bauer). Later, the two officers stake out the boss's wife, Helena (a pregnant Catherine Zeta-Jones). Cheadle and Guzman, who were last paired in Soderbergh's Out of Sight, make a terrific comedy act. They deliver some dialogue, maybe improvised, that would be a credit to Elmore Leonard or James Ellroy. In the third section, Robert Wakefield (Michael Douglas), an Ohio Supreme Court justice, has been tapped as the new drug czar appointee. He's been picked for his hard line on drug crimes, rather than for any particular understanding of the drug war. While Wakefield concentrates on accepting this high office, he continues his neglect of his wife (Amy Irving) and daughter, Caroline (Erika Christensen), who is already experimenting with smoking heroin. Traffic is best in what looks like the potentially weakest section: the family drama. Christensen's Caroline is scarily apt; she makes the girl's junk addiction look like first love. Soderbergh films the scenes of her initial encounter with heroin in the same blue-white lighting we saw in the drug rapture scenes in Requiem for a Dream. But why is this film more exciting to the eye? Probably because Soderbergh doesn't water down the drug's allure with moralizing. He goes along with the experience; he takes the scorpion attack out of it, watching the fresh-faced girl's tears of awe and gratitude when she gets the full feeling of the rush. Caroline's first experience with dope takes place at the end of a brilliantly observed party scene. It consists of a few minutes of overlapping dialogue between prep-school kids in the living room of an Ohio mansion. The camera weaves about, overhearing the aimless talk--aimless, yes, but not static. These are not the dull slangy teens of the anti-drug commercials. These students are the bright ones. Drug war propaganda tells us that kids take drugs out of stupidity and nihilism. But not all do. Some are searching for the uncompromising emotional truth they believe the drugs might reveal. To them, their parent's lives are hypocritical, a dull charade. Thus Traffic shows the disconnection between the drug policy makers and the drug fanciers, each unable to understand each other. Though comic in parts, Traffic is tragic in its whole. Soderbergh's approach is that the misunderstanding would be farcical if there weren't lives at stake. I'VE READ THAT one of Soderbergh's techniques involves balancing the camera on a sandbag instead of a tripod. The director says that what he's trying to achieve is a camera that isn't firmly "nailed down." Soderbergh's earlier film, Erin Brockovich, wasn't nailed down either--and was all the better for it. The solvent hasn't been distilled yet that would remove the polish from Julia Roberts. Erin Brockovich worked so well in spite of Roberts because of Soderbergh's use of ordinary (rather than extreme) locations. Often, a director might ask his locations person to find the biggest house or the ugliest hovel. In Erin Brockovich, none of the settings looked like the result of an exhaustive search. The L.A. locations were phenomenally anonymous--flat, shabby desert courthouses, burnt lawns, beat-up tract houses, cut-rate lawyers' offices. If Roberts seemed awfully glamorous to be a poor single mom, that was fine; she was believable enough because her surroundings were a poor single-mom's surroundings. In Traffic, Soderbergh adds to his story's credibility with his locations. The film takes place all over the map, in the mansions and slums of Cincinnati, doubling for Columbus' slums. The narrative takes us from Washington, D.C., to the Sonora desert in Tijuana and to the El Paso Information Center, called "EPIC" (there's the kind of tough acronym we need to end the scourge of drugs!). Soderbergh, who photographed Traffic under the pseudonym "Peter Andrews," repeats his visual tactic from Out of Sight of filming the snow-belt scenes through a blue filter and the hot-country scenes through a bronze filter. This isn't noteworthy as a visual innovation alone--tinting goes back to the silent days. But here Soderbergh proves that tinting can be used to overcome the monotonous color that's the chief problem of the low-resolution, portable cameras he uses for much of this film. Because of the color scheme, the film is as sensually exciting as it is quick and raw. Traffic never loses its way, no matter where it wanders. Traffic isn't perfection; it's too fast, too ambitious, too sprawling to have that unity perfection demands. Wakefield tours the auto checkpoint at the U.S. border and EPIC, where the desert routes into the U.S. are watched by satellite and patrol. These scenes are desert-dry, more strictly informative than entertaining. Zeta-Jones uses her natural-born English/Welsh accent for a change, but she's wrestling with a vaguely written character. Her Helena is a rich girl raised out of poverty or something. Now she's a matron in training; later, she turns out to have the makings of a criminal. In an action scene involving a sniper and a bomb-laden car, Soderbergh's staging is very ordinary. Moreover, a Narcotics Anonymous meeting at the end should have been shown without dialogue. There may not be a way to dramatize a 12-step meeting in a film, even if these scenes are good for the soul. Such groups do more to fight the drug problem than anything guns or TV commercials can do, and they cost far, far less. But in 12-step-meeting scenes on film, everything exists on one flat level. Usually, such meetings encourage complete acceptance of what the speaker is saying. Thus there's no counterpoint to what we're seeing and hearing. Despite the errant moments, Soderbergh has once again converted political drama into entertainment, with mastery that hasn't been equaled in years. John Sayles works in this direction, too, but Soderbergh is a far stronger visual storyteller. The new year in movies opens with this important analysis of our national obsession--a Hundred Years' war, born in nativist, racist terror and suckled by opportunistic politicians. It's a dirty war, a civil war. Years of study and suffering, an inconceivable amount of money and lives spent--maybe the first step away from the vortex is to stop thinking in terms of good guy and bad guy, urban warrior vs. giant scorp. The incoming drug czar will have a number of duties. His or her first duty ought to be an afternoon with Traffic.

Traffic (R; 147 min.), directed by Steven Soderbergh, written by Stephen Gaghan, photographed by Peter Andrews and starring Michael Douglas, Catherine Zeta-Jones and Benicio Del Toro, opens at selected theaters. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the January 4-10, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.