![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Usual Suspects

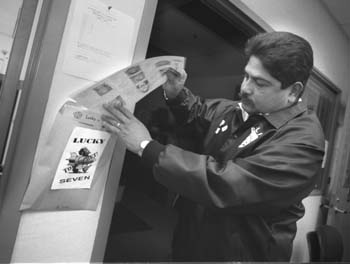

Christopher Gardner Better Than a Garlic Necklace: Gilroy police corporal Daniel Castaneda, who heads the anti-crime unit, says continual tracking of the 'Lucky Seven'--people with police records--has reduced crime in this rural south valley town. An elite crime-fighting unit of the Gilroy police has a policy of shadowing certified trouble- makers until they land in jail or leave town By Jim Rendon ON A DIMLY LIT SUBURBAN STREET, five Gilroy police officers move stealthily away from their unmarked cars and fall quietly into formation. Gilroy Police Corporal Daniel Castaneda stands on the sidewalk, his hands hanging loosely on his hips above his gun, just in case. Two more officers take their positions on either side of the porch of a small, unremarkable house. At the door, the probation officer, wearing a mesh vest with "Probation" printed across the back in red letters, takes his position next to an officer with "Police" lettered from shoulder to shoulder. With a loud knock on the door, the officers announce themselves. After a minute, a small light-haired woman peeks out the door. With little fuss, she lets the officers inside. Except for the jabber of the police radio in the unmarked car, it's quiet outside the house on Rosanna Street. Every now and then a police flashlight beam shoots across a darkened window. Toward the back of the home, a light flashes on, then off, then on again. Another flashlight weaves through the bushes in the back yard, like someone brushing away brambles on a midnight hike. But this light is looking for trouble. And tonight, it will find it. In black, unobtrusive uniforms and unmarked cruisers, members of the Anti Crime Team of the Gilroy Police Department don't need a warrant or even the suspicion of wrongdoing to search the Rosanna Street house. The woman who lives in this house is on probation with a condition that allows her home to be searched at any time, for any reason. Her door is always open to her probation officer and to the police. Tonight officers searched her home because she failed a drug test. "Based on that information, we went in to see if there was anything else in the house," Castaneda says. Any time day or night they can show up and search her house and hundreds of others that are occupied by people put on probation by the courts. IN HIS OFFICE at police headquarters Castaneda, a dark-haired man wearing a snug-fitting bullet-proof vest, hands me a legal-size sheet of pink paper. Seven pictures, all boys with close-cropped hair, are arranged in rows. The boys are mostly Latino, one looks Filipino, none are white. Four of the seven are juveniles, he says. The people on the current list of troublemakers include a suspected local gang leader, a person with a warrant out on an attempted murder charge, the leader of a graffiti group and an escapee from a minimum-security probation ranch who was originally locked up for assault. These seven mugs, and the dozens who came before them who have been removed from the list by arrest, are the nexus of Gilroy's crime problem, according to Castaneda. The individuals, dubbed the "Lucky Seven," are targeted by officers for daily contact. Any of the seven who is on probation or parole gets his home searched regularly. Other parolees that the department sees as troublemakers are also visited, searched and checked up on. Castaneda is blunt about the program's purpose. "Either you straighten out, or we will be your shadow," he says. "We stay within their rights," he says, but admits, "It's borderline harassment." The city of Gilroy--the cops, the mayor, the City Council--have come together with a shared goal: to get these undesirables out of town one way or another. Since the program went departmentwide in June of this year, 29 people have made it onto Gilroy's Lucky Seven list. Of those 29, the vast majority--21--have been arrested for violations of probation or parole or for other crimes. Two people have moved out of town. No one has cleaned up their lives enough to be removed from the list. Strong supporters of the program such as Gilroy Councilman Tom Springer say it stays within the letter of the law and gets the message across: Crime will not be tolerated. "It gets the focus of all the troops, the officers on the street, the detectives and everybody else," he says. "The guys that make the list are the most troublesome. In some cases the people move away. They don't want to stay in Gilroy. What that might mean for some other community I can't say, but it keeps our streets clean," he says. HALF AN HOUR AFTER banging on the door, the officers emerge from the Rosanna Street house. The probation officer hoots into the cold night air. The cops chatter loudly, like a bunch of boys leaving a party, pockets stuffed with phone numbers. This time, they got lucky. When the cops entered the house, they saw someone running for the back room, Castaneda tells me. A housemate had apparently been smoking pot. Though he was not on probation, his housemate is--so his door and his life are open to the officers as well. And, Castaneda says, police also confiscated a valuable piece of incriminating evidence: a home-manufactured weapon. As Castaneda tucks the valuable evidence into the trunk of the car, my mind spins with the terrifying possibilities: cobbled-together handguns, plastic explosives, modified semi-automatic rifles, homemade pipe bombs ... Castaneda explains that the weapon was a good enough find to take to the DA. He feels confident there will be a prosecution on this one. "What was it?" I ask. He looks at me, a note of pride in his voice. "Screwdriver," he says. "Filed to a point." I look back at him in the dark, searching for a wry smile, a facial tic--anything to betray this little joke. But there is nothing. "You know, like an ice pick," he says, in a dead-serious voice.

But because Gilroy is a small town of 34,000, the numbers for other violent crimes are low. There were two murders in 1996, three in 1997. There were only 45 reported robberies in all of 1997. Commensurate with the low numbers of varied crime, the Lucky Seven are not drug kingpins who have their homies shoot up neighborhoods with AK-47s. Lucky Seven poster children can be just about anybody who bumps into the edges of the law. "If you are active. If you are doing crime that affects neighborhoods or affects the city, or if you are involved in gang recruitment, or a nuisance where you're suspected of giving booze to underage kids, you can get on the list," Castaneda says. Even someone who officers suspect may repeat a crime like spousal abuse can land on the list. Without being on probation or parole or even under suspicion for any particular crime, someone could end up as one of the Lucky Seven. GILROY STOLE the Lucky Seven idea from Paramount, the home of Great America, in the part of Los Angeles County that brushes up against famously conservative Orange County. In the early 1990s, that town's police force was looking for a way to track repeat offenders. But rather than just keep tabs, they made the leap to targeting people to watch for prosecutable crimes. In 1995, Gilroy police officers heard about the new approach at a police conference and brought the idea home with them. A year and a half ago, the Anti Crime Team began working out the kinks of the Lucky Seven program. Last year the program went departmentwide, gaining support from the mayor and City Council. Although Gilroy cops often come up short on their forays, they take their tough stance very seriously--a little too seriously for Aram James, an attorney with the Santa Clara County public defender's office. He balks at what he sees as California's long strides toward becoming a police state. The situation riles James so much that he has printed up bumper stickers, a few of which might find some use in Gilroy. One reads, "Is this a police state?" Another says, "I do not consent to a search of my person, vehicle or residence, so don't ask." Proactive police units like Castaneda's have a habit of targeting youth and people of color, James says. None of the faces on the Lucky Seven list that I saw were white, and the majority were juveniles. Of the nearly 30 people on the list thus far, Castaneda says, three were white. Though the town of Gilroy is approaching a Hispanic majority (according to the 1990 census, Gilroy was 47 percent Hispanic), the Lucky Seven numbers do not reflect the town's racial composition. "If they use this program to target a particular group, then it could be argued that it runs afoul of the equal protection clause [of the U.S. Constitution]," James says. Under the Constitution, all citizens have the right to receive equal treatment. It's one of the reasons that segregation fell, and it protects minorities from targeted investigation. "That these people are youth and all minority is extremely troubling," James says. "We see a whole lot more of this kind of policy in California. This state imprisons more people per capita than anywhere else on the planet." Yet no one in Gilroy seems to have a problem with the program. Guadalupe Arellano, usually a liberal voice on the Council, has embraced the program. "My understanding [of the program] is that we're going to sit on this person till we get them," she says. "We're going to watch and make sure he knows we're watching and deter crime. Suppression walks a lot of fine lines. Part of suppression is to let people know we're out there," she says, adding, "I feel comfortable that the program is a tool used to solve crimes." Even the Northern California chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union doesn't see anything illegal. "I don't want to appear to sanction this or to give it the ACLU blank check," says John Crew, a police practices attorney with the Northern California chapter of the ACLU. But Gilroy's cops, he says, are not breaking any laws. "The line changes on probation or parole with search clauses," he says. "Tactics that would otherwise be blatantly unconstitutional are permissible when someone is on probation or parole." The Gilroy Police Department knows the important link between probation and the work that they do. Of the 500 adults and juveniles on probation in the town, 75 percent have a search clause attached to their probation. Mike Clark, a Santa Clara County probation officer assigned to the unit full time, goes along with the officers on their searches. Other probation officers sometimes ride along when their clients are on the list for a search. "If there is a search clause on the probation, I am the key to the house," Clark says. "We don't violate people's rights," he says. The unit uses the law to its advantage, he explains, and is a much more organized way to approach the work. The probation officers know the people they work with. The police officers use that existing relationship to gain entry, gather information and keep tighter tabs on people who may be more prone to commit crimes, Clark says. But on the other hand, many of these people are not suspected of committing any specific reported crime. The officers are just waiting for a slip-up. And more often than not, they get it. ON THE WAY to the next house search, Castaneda suddenly swerves into a parking lot. He and the officers driving behind him jump from their cars and surround a teenage boy. They check his ID and call it in. A few minutes later a police sport utility vehicle joins the two unmarked cars. A uniformed officer gets out, cuffs the young man and hauls him into the truck. Another officer picks up a beer can next to the wall, looks it over and drops it back on the ground. Castaneda tells me the officers thought they saw the young man throw the beer can aside, so they pulled over to question him. But it turned out the can was bone dry, obviously left there for some time. After running the license, the unit turned up an outstanding warrant for unpaid traffic tickets totaling $3,000. He'll get booked and spend a little time at the Gilroy Police Department while they find him a new court date. And that's life for someone who could be one of Gilroy's next Lucky Seven. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the January 7-13, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

TO SAY THIS UNIT takes its mission to heart is an understatement. While it has its share of underclass neighborhoods and drugs, Gilroy is far from a crime-ridden slum. Enrique Colin, who handles felonies for the public defender's office in south county, says he sees mostly drunken driving and drug possession cases. The few violent cases that make their way through his office are domestic violence cases, he says. In 1996 and 1997, Gilroy's serious crime rates varied little from California's average. The big exceptions were aggravated assault, which was double the state's rate, and car theft, which was much lower than the state's average.

TO SAY THIS UNIT takes its mission to heart is an understatement. While it has its share of underclass neighborhoods and drugs, Gilroy is far from a crime-ridden slum. Enrique Colin, who handles felonies for the public defender's office in south county, says he sees mostly drunken driving and drug possession cases. The few violent cases that make their way through his office are domestic violence cases, he says. In 1996 and 1997, Gilroy's serious crime rates varied little from California's average. The big exceptions were aggravated assault, which was double the state's rate, and car theft, which was much lower than the state's average.