A Pete for the People

Folk great Pete Seeger is set to sing for San Jose Peace Center

By Tai Moses

DURING FOLK LEGEND Pete Seeger's induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame two years ago, Harry Belafonte praised the singer's dedication to social activism, saying, "If they ever decide to put a fifth face on Mount Rushmore, I would nominate Pete Seeger. He is one of the great sons of this country." In one of the many ironies in his extraordinary life, Seeger was unable to hear Belafonte's praise: he had forgotten to wear his hearing aid that evening.

At 78, Seeger's wiry frame may be a little bent and his legendary voice may have faded to a quaver, but the years have done little to diminish his passion for music or his belief in the progressive causes he has championed for nearly six decades. The times they may have changed, but Pete Seeger remains an indelible influence upon the country's political and musical landscape.

I can't remember a time when I didn't know the name of Pete Seeger. I knew the words to his songs long before I understood their meanings. Folk music was a constant presence in my childhood, beginning with the antiwar and civil rights anthems made famous by Seeger and Woody Guthrie.

I can still hear the familiar strains of "Where Have All the Flowers Gone" and "If I Had a Hammer" sung by thousands during the Vietnam War protests I went to with my parents in Griffith Park in L.A. During the AFL-CIO strikes of the early '70s, we walked the picket lines with our neighbors and sang Seeger standards such as "Which Side Are You On?" "Union Maid" and "Hold the Line."

I loved the old songs that Seeger and Guthrie had collected during their travels around the country and popularized--songs about shipwrecks and prison breaks, hobo lullabies, freedom songs and slave spirituals, love ballads and blues. Like Seeger, my father had been a Communist Party member, and if there was any religion in our house it was the working man's faith; our catechism was Seeger's gentle exhortation to keep fighting the good fight.

It's not easy to write about Seeger without invoking clichés. He is an authentic national treasure, a tireless patriot, an artist who has never surrendered to cynicism or wavered from his outspoken commitment to the ideals of freedom, brotherhood, peace and justice. As a musician, he's a force of nature, a virtuoso of the 12-string guitar and an elegant banjo picker.

The details of Seeger's history are as familiar to most folk-music fans as the words to a favorite song. The son of musicologist Charles Seeger, Pete attended Harvard like his father but dropped out after two years. He joined the Communist Party, learned to play the banjo and met musicians like Leadbelly and Blind Lemon Jefferson, who introduced him to the traditional black folk music of the hills.

In 1940, Seeger helped form the Almanac Singers (which Woody Guthrie would join in 1941). Two years later, he and Guthrie sang "The Sinking of the Reuben James" on a CBS network radio program, and the nation awoke the next morning to newspaper headlines that declared, "Commie Folksingers Try to Infiltrate Radio."

Seeger founded the Weavers several years later, and the group had a string of hits until it was blacklisted in the McCarthy era. It is sobering to recall that Seeger was once considered such a threat to the establishment that for 16 years he was banned from appearing on network television. Today, the man once accused of being anti-American holds a National Medal of Arts, and in 1995, he received the nation's highest cultural honor: the Kennedy Center Honors Award.

TO ATTEND a Pete Seeger concert is to participate in a unique musical ritual not soon forgotten. The tall skinny man with the banjo-string neck and the resonant nasal twang has a rare ability to electrify a crowd, with his storytelling and humor, his fiery spirit and innate compassion. I have friends who still recall, with misty eyes, Seeger performances they attended as children, as teenagers or as college students.

The last thing Seeger wants from an audience is rapt silence; he is famous for dividing audiences up, teaching them the choruses to the songs and getting them to join in--sometimes in three- or four-part harmony. "My main purpose is to get a crowd singing," he has often said.

With Seeger gleefully shouting out the words in the breaks between verses, somehow the whole thing hangs together and transcends one's idea of a conventional concert. This is Seeger's ideal: the power of song to effect change, song by song, voice by voice, a singing revolution. Seeger's performances are a kind of participatory collective experience--they're art, community and politics all rolled into one.

Seeger's upcoming Silicon Valley appearance, a Martin Luther King Jr. day benefit for the San Jose Peace Center, seems especially relevant in light of the singer's ideas about art and technology. The liner notes to his Grammy-winning CD Pete (Living Music) include some cautionary words that techies would do well to heed:

Modern artists have a responsibility to encourage others to be artists. Why? Because technology is going to destroy the human soul unless we realize that each of us must in some way be a creator as well as a spectator or consumer. Make your own music, write your own books, if you would keep your soul.

These days, Seeger often sings with his grandson, Tao, whose stronger voice helps support his grandfather's weaker one. But even if Seeger's celebrated pipes dwindle to a whisper, his music will never disappear. His voice will always have a permanent home in the hearts and memories of the people.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

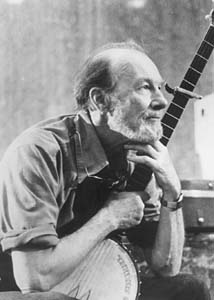

A Son of the Country: Pete Seeger's goal has always been to get people singing.

Pete Seeger, Bob Reid and the Oakland Youth Choir will perform Thursday (Jan. 15) at 7:30pm at Foothill College, 12345 El Monte Rd., Los Altos Hills. The show is a benefit for the San Jose Peace Center celebrating the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. Tickets are $17/$20/$30. (BASS 408/297-2299)

From the January 8-14, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)