![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Paint it Black

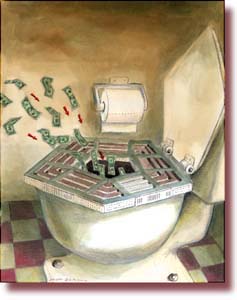

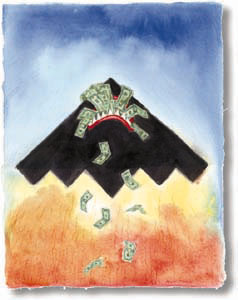

Billions of taxpayer dollars are vanishing into a fiscal black hole. Are we making a down payment on World War III or needlessly selling out to Cold War spooks?

By Christopher Weir

IN WHAT REMAINS ONE OF THE MOST significant yet elusive developments in this era of deficit reduction and budget slashing, top-secret phantoms have emerged from the rubble of the Cold War to perpetuate an impenetrable, unaccountable and mystifying $30 billion shroud: the Pentagon's black budget. This budget, both a cover for vital national secrets and a wasteful proving ground for theoretical world wars, conceals hundreds of programs, many of which propel the economic engines of Silicon Valley.

The black budget operates without constitutional authority or broad congressional oversight and is a hive of absurdly speculative and astonishingly expensive hallucinations, including the notion of "winning" a full-tilt, six-month nuclear war synchronized by a satellite network that charts the progress of the apocalypse. It is also the nerve center that allows us to sleep relatively peacefully in an unstable world increasingly plagued by the threats of nuclear and chemical terrorism. The black budget is, indeed, the good, the bad and the ugly of postmodern militarism. And many are now questioning the ethical, financial and constitutional premises that allow such a phenomenon.

"Most citizens accept the need for secrecy in times of crisis," writes defense researcher and journalist Bill Sweetman. "And most would accept the need for the country to pursue technical breakthroughs sheltered from prying eyes. But the question is whether a secret military should be such a thriving, unaccountable institution when the security of the nation is less threatened than it has been for decades."

Silicon Valley promises to take weaponry

SDI is rearing its high-tech head again too.

Shades of Black

THE DIFFERENCE between black programs--officially termed "special access programs"--and those merely employing classified activities is simple: A black program is one in which the identity, purpose and even costs of the entire operation are concealed not only from taxpayers, but also from a majority of congressmembers. And secrecy itself comes at a significant price, adding, by most estimates, about 25 percent to a program's cost in physical and informational security. This figure does not take into account the waste and fraud that many contend are inherent in a system that evades public--and often internal--checks and balances.

Authorization for special access programs is granted by the President, in this case an executive order of President Clinton's, which was a reformulation of a previous order by Ronald Reagan.

"The immediate problem with secret budgets is that you lose a great degree of oversight and accountability," says Steve Aftergood, director of the Project on Government Secrecy for the Federation of American Scientists. "In the best of cases you end up wasting money. In the worst of cases you have abuses of power."

Similar concerns inspired Article 1, Section 9, Clause 7 of the United States Constitution, which states, "No money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in consequence of appropriations made by law; and a regular statement and account of the receipts and expenditures of all public money shall be published from time to time."

THE MILITARY'S portion of the black budget inhales about $14 billion annually. This figure overlaps to some degree with integrated intelligence activities, while billions more in black money support the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, the National Reconnaissance Office and other intelligence operations. According to several researchers, the total cost of black-budget programs today stands at about $30 billion.

"To a large extent the military, and certainly the intelligence community, is still running on Cold War momentum," Aftergood says. "A lot of projects that were initiated in the late 1980s are still under way, and it seems as if they're unstoppable, despite the fact that the mission which inspired them has vanished."

The remnants of the Cold War are not limited to the black budget and other motivational paradigms that linger within the halls of the Pentagon. The tensions between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union resulted in the idea that funding a multitude of hypersecret military programs was patriotic, an integral part of democracy itself. Indeed, there was a time when such intuitions perhaps made sense. The question is whether or not that time has passed. Because if it has, the fiscal and constitutional implications are immediate and overwhelming.

"It is not discussed," says one Pentagon source about cost-cutting in the black budget. "If you look at the appropriations bill, you won't see anything under black programs. That's just the reality."

In this state of obfuscation, Americans can only wonder just what isn't being discussed, and what kind of reality is being forged. Prior to the Manhattan Project--where the power of the atom sparked wartime concerns and stealthily diverted funds--secret military budgets did not exist. The atom bomb was the catalyst for the black budget, which merged postwar distrust with weapons of mass destruction. Two years later, with the establishment of the CIA, the black budget became a government fixture, its boundaries systematically expanding throughout the Cold War.

"If you look back to the 1950s and 1960s, the only programs which were black were those that dealt with reconnaissance," Sweetman says. "With the stealth [aircraft] programs in the 1970s, you started to see the black world overlapping more with the world of regular military operations."

In the 1980s, black-budget military programs went into overdrive, and their costs were considered a sacrifice to the national mandate of spooking and spending the Soviet Union into oblivion. Yet as the Cold War recedes farther into America's rearview mirror, secret military spending remains close to its Reagan-era high.

"We tend to know less and less about this as time goes on," Sweetman says. "We don't know as much as we used to simply because nothing much has been disclosed from the black side of the budget" since the late 1980s. Almost 40 cents of every dollar budgeted for Air Force equipment is dedicated to secret projects, he says.

In Acronymity

BLACK MILITARY programs appear as budget-request line items bearing acronyms, code names or generic catchphrases, such as STUDS, Tractor Rose or "special evaluation program." Their total costs are usually withheld. They are justified not to Congress as a whole, but rather to elite committees like the Senate Armed Services Committee and the House National Security Committee. The most secretive, or "waived," programs need only be revealed to the committee chairperson and the senior minority member. The only people providing core information on black-budget military programs are those who have a large stake in them: the relevant military personnel and their contractors.

The deficiencies of this arrangement are best exemplified by the A-12 Avenger, a Navy stealth attack fighter that ran recklessly over budget and was ultimately cancelled in 1991. Inquiries by the Navy and the Pentagon's inspector general determined that excessive secrecy disallowed routine oversight, and even the Secretary of Defense was not properly informed of the program's troubles. According to Aftergood, the Navy spent $2.68 billion--more than twice the annual amount dedicated to the National Park System--on the A-12 program. "Since the program was terminated before completion," he says, "no planes ever became operational, and all of the money was essentially wasted." He adds that a complex lawsuit filed by A-12 contractors for alleged improper termination may ultimately cost the government an additional $2 billion.

The very nature of the black budget suggests that if a similarly plagued secret program exists today, it will be years before Congress' General Accounting Office and other agencies can sift through the debris and trace the wasted billions.

Such a troubled program could exist in the form of a hypersonic Mach 6 (4,000 mph) spyplane that has been the focus of much speculation since a line item encoded "Aurora" took a budget leap from $8 million in 1986 to $2.3 billion the following year. Aurora then disappeared from the ledgers as it receded deeper into the black. Through much historical and technical sleuthing, Sweetman has placed himself at the vanguard of those who believe Aurora--also known as Omega--is today an active project with operational aircraft. And in his book Aurora: The Pentagon's Secret Hypersonic Spyplane, he concludes that "it is entirely possible that not all the news about Aurora is good. Secrecy has often been a cover for technical and financial problems ... Aurora may have overrun its projected costs or it may be designed and equipped in such a way that it is dedicated to an obsolete nuclear warfighting mission. Sooner or later, that story will come out."

Meanwhile, those privy to such stories are perhaps unprepared to deal with them. As quoted in the Secrecy & Government Bulletin published by the Federation of American Scientists, a senior Pentagon security official describes the congressional committee oversight as "perfunctory." He adds, "In my experience, it's usually staffers, not (committee) members, and it's a small cadre. ... Once a year or so, people will go up there and brief them on the particulars. Often it's several programs in one sitting. It's going through the motions."

Lee Halterman, general counsel to House National Security Committee member Ron Dellums, disagrees. "There are exactly the same problems in the open budget as there are in the special access budget," he says, citing institutional pressures and industrial base issues. "The advantage that the staffer or member who is working on a nonspecial access program has is that the public, citizens, watchdog groups...can bring their insights to the table, which is often useful and important." For that reason, he says, committee members and staffers recognize that an extra degree of diligence is required in assessing special access programs.

While the committee staffers are neither elected nor open to public input, they remain accessible to program contractors. "The contractors who stand to benefit from the funding decisions," Aftergood says, "are free to lobby the staffers."

According to the Sept-Oct 1995 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, published by the Educational Foundation of Nuclear Science, all of the top ten defense contractors in the U.S. were convicted of or admitted to fraud during the period from 1980 to 1992.

Tales of Groom

NEVADA'S GROOM Lake--the top-secret test site for the nation's most advanced military technologies--remains symbolic of outdated secrecy measures taken to absurd extremes. In 1995, the Clinton administration authorized the Pentagon's seizure of 3,900 acres that included distant peaks from which military technofreaks had long been gawking at the base. This was land that even the Reagan administration ignored during an 89,000-acre Groom Lake land grab in 1984. The cost of literally denying Groom Lake's existence--from patrolling its ever-expanding borders to managing rigid security clearances to shuttling hundreds of workers daily in unmarked jetliners--is enormous. This continues, despite the fact that Groom Lake (also known as Area 51) is so well known that it has become a pop culture fixture, inspiring everything from informed speculation on cutting-edge aerodynamics to offbeat UFO conspiracy theories in the movie Independence Day.

"It's really absurd to try to mask or obfuscate the existence of Groom Lake," Sweetman says. "We know it exists. Why should you not declassify at least as much information as is already available to any foreign intelligence service? Any foreign intelligence service knows far more about Groom Lake than the American public does. It's the same with spy satellites. They can be imaged in orbit fairly easily ... So why do we go through the song and dance of denying that there is such a thing as the KH-12 (spy satellite)? That makes no sense. It's a waste of time, it's a waste of money, and there's no point to it."

In his definitive book Blank Check, Pulitzer Prizewinning journalist Tim Weiner charts not only the black world's courtship of waste and corruption, but also the capriciousness with which costly secrecy is too often levied. For example, just after the B-2 stealth bomber emerged from 10 years' worth of secret research and development in 1989, main contractor Northrop flooded Washington, D.C., with television and newspaper advertisements to lobby a Congress that was still in shock over the program's staggering costs. "Northrop's ads had a ludicrous aspect," writes Weiner. "Until a few months earlier, it was a crime to discuss the bomber in public. Now here was this prime-time publicity campaign for the secret weapon."

Green Camouflage

THE BLACK budget is also a potential safe haven for environmental crimes, simply because lack of outsider access and oversight creates a regulatory vacuum. For example, a recent suit--filed on behalf of six craftsmen who report serious health problems ranging from skin disease to cancer--alleged that Air Force contractors in the Nevada desert illegally burned toxic chemicals in open pits. The Air Force responded by invoking a secrecy privilege, arguing that disclosure of any information regarding the secret base--even the mere identification of the chemicals burned--would potentially create "exceptionally grave" consequences for national security. After the workers challenged the Air Force maneuver, Bill Clinton signed a presidential exemption that reconfirmed the secrecy privilege "in the paramount interest of the United States." In dismissing the workers' lawsuit last March, a federal judge concluded: "When properly invoked, the (secrecy) privilege is absolute." The suit is now under appeal.

Environmental questions also surround a white Navy project: Low-Frequency Active Sonar (LFA), a submarine-detection network that floods the oceans with intense pulses at 235 decibels. While the project is still working its way through the environmental impact statement process, the Natural Resources Defense Council and others are charging the Navy with secret LFA tests in violation of several federal environmental laws. The Navy maintains that environmental impacts are being closely monitored. Regardless, the LFA project illustrates the shades of gray that sometimes connect black and white military projects.

Aftergood says he recognizes the role secrecy can play in protecting sensitive technologies or intelligence operations. But he questions both the breadth of current secrecy trends and the practice of shielding black programs' costs from Congress and taxpayers.

"In almost all cases, secret budgets should be eliminated in the current security environment," he says. "That is dictated not only by constitutional considerations, but also by management and security considerations. The simple reality is that knowing the cost of a B-2 bomber tells a potential adversary nothing about how to build or defeat a B-2 bomber. Secret budgets are therefore indefensible, in most cases, on security grounds."

Asked what would be the advantage of making public the identity and total cost--and perhaps nothing more--of a black program, Aftergood replies, "Most of the public policy debate does not revolve around the details of technology. Rather it concerns mission requirements and comparative costs. In other words, should we be devoting such-and-such amount of money to one thing, when a competing national interest on the civilian side is being cut? Those kinds of public policy considerations do require information about spending, but not necessarily about technology details. A greater degree of disclosure would facilitate discussion of mission requirements."

Sweetman, however, thinks that the black world's primary folly is its tendency to support overbearing, costly and cumulative secrecy. "The biggest thing that needs changing," he says, "is an improvement of declassification. At the moment, special access programs are a one-way trapdoor."

Beyond this door is a wonderland of exotic arsenals, engineering brilliance and ghoulish premonitions. Ten years ago, it was largely a production line of nuclear war machines, of dazzling ground-zero communications networks and underground "continuity of government" bunkers from which generals would orchestrate the symphony of mutual assured destruction. Today, it aspires to refine the future of warfare, in which analysts predict reliance on such things as directed-energy weapons (lasers), unmanned combat aircraft and lingering SDI (Star Wars) systems.

The Cold War may be over, but the nuclear genie is out of the bottle and the new world is still in disorder. Officials from Los Alamos National Laboratory testified to Congress earlier this year that more than 20 countries are suspected of nuclear, biological or chemical weapons proliferation. And the embittered Russian nuclear priesthood appears inceasingly tempted by the black market for bomb-grade plutonium. Clearly, the challenges facing the United States military and intelligence agencies should not be oversimplified or diminished.

But in the wake of the Soviet Union's collapse, the $265 billion United States defense budget seems sufficiently dominant, whether above or below board. It stands at 120 percent of the combined military budgets of the next nine biggest spenders, including China, Russia and the European allies. It is 15 times the combined amount spent by the militaries of our regional adversaries: Libya, North Korea, Cuba, Iraq, Syria and Iran.

Fifteen years ago, a staggering surge in black defense spending was justified as a last resort, the cost of keeping an edge on a clearly defined and mightily armed enemy. Now that no such enemy exists, on what grounds can the perpetuation of such secret spending levels be justified?

"Unfortunately," says Paul McGinnis, a researcher noted for his ability to navigate the black budget's fiscal hall of mirrors, "military authorities and senior members of Congress seem to feel they do not owe any explanation for their actions to the American public."

Halterman counters that the military is increasingly sensitive to public and budgetary concerns, and that the Dellums camp--and others in the committee realm--are working hard to evaluate and modernize special access infrastructures: "Mr. Dellums has, from his very first days in Congress, pressed hard to declassify and remove the special access designation from programs for which those classifications can't be justified," he says. "We believe that in this postCold War environment there is an opportunity to reduce significantly programs both within the special access account and outside of it."

While some special access programs have arguably served the country's best interest--producing highly successful aircraft programs and intelligence coups--the black budget must still contend with a legacy of abuse, fraud and waste created by a lack of oversight. This legacy ranges from illegal human radiation experiments in the 1940s to the recent A-12 fiasco, and it prompted the House Armed Services Committee to observe in 1991 that "the special access classification system...is now adversely affecting the national security it is intended to support."

Since then, however, little has changed in the covert world. What was once a financial and constitutional sacrifice to a Cold War mandate has become a $30 billion way of life in peacetime. And the increasing numbers of questions now being asked remain largely and characteristically unanswered.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Illustrations by Mott Jordan.![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

to technological heights.![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Cold Infusion

From the January 9-15, 1997 issue of Metro