![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Through a Burka Darkly

Mohsen Makhmalbaf imagines life under the Taliban in 'Kandahar'

By Richard von Busack

ANYONE HEADING to Kandahar in hopes of discovering current news about the Afghans will be let down. Since director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, an Iranian, wasn't allowed into the country, he had to create his own version of Afghanistan. The city of the title is a nightmare fiction dimly glimpsed. We see it but never enter it--only gazing at it in a final shot through the latticed porthole in a burka, the human-sized dust-covers women were forced to wear by order of the government.

This supposition of what life might be like in the realm of the Taliban is inspired--a circus of oppression Pynchon-like in its weirdness and sick comedy. It's been rumored that President Bush had requested a screening of Kandahar. I'd pay good money to see the look on his face during one of Makhmalbaf's characteristic surreal scenes--say, for example, the image of a single prosthetic leg plummeting from the sky at the end of a parachute.

Makhmalbaf has said repeatedly that "the hero of Kandahar is the people of Afghanistan." Not exactly. The hero is actually the film director himself, making up a foreign land out of anecdotes, the desert and a cast of nonprofessionals.

Since we commonly liken Iranian films to Italian neorealist work, we often forget the way these films are more than simple records of simple people. Consider Makhmalbaf's fanciful streak, as in Gabbeh, in which a hand-loomed carpet tells the story of a star-crossed love. In his best film, A Matter of Innocence, real-life tragedy interferes with an attempt to make a dramatic reenactment of a life-changing moment in his past.

Makhmalbaf, working under poor conditions, possesses a quality most of today's cinematic fantasists lack: brevity. The standard form of the Iranian film--90 minutes tops, black-and-white titles--ensures urgency. The fantastic adventures of Kandahar may be strange, sometimes florid. Still, their course runs fast; Kandahar has the fantastic inevitability of a murder ballad. The events may seem strange, symbolic, but they are built on real incidents.

Kandahar is a quest picture, derived from a true story. The heroine, Nafas (Nelofer Pazira), an Afghan émigré living in Canada, receives a distressing letter from her sister, left behind in Afghanistan. Left legless after a mine explosion, the sister plans to kill herself.

Nafas heads to the forbidden country, led by a series of guides. A native man, carrying a U.N. flag, disguises Nafas under a burka. She encounters a child recently kicked out of a madrassah. The child's disobedience provides a rich comic moment as he tries to bluff his way through a Koranic text that he doesn't know how to read.

The traveling woman finally stops at a Red Cross center, where a party of amputees has a long wait for prosthetics. The amputee scene is awkward because of the semi-improvised acting by the European nurses. The ballet of the legless on crutches staged for our benefit is too gratuitously painful. The tangle of languages here prevents either naturalism or stylization; the sequence seems haphazard.

Nafas' final guide is an African American Muslim doctor (Hassan Tantai), a volunteer who hides behind stage whiskers because he can't grow a beard. Tantai is a natural, but perhaps his air of penitence is no act. (According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Tantai is under suspicion as the fundamentalist assassin who, in 1980, shot a liberal Iranian official opposed to the Ayatollah Khomeini.) Tantai examines the ailing Nafas through a peephole in a curtain, because even doctors aren't allowed to view these shrouded women.

Throughout the film, we see images of a backward, tormented land: the shuffling parties of women herded across the desert, blankets over them as if they were characters in some avant-garde play; beautifully ornamented three-wheel carts puttering across the sands, leaving from nowhere and going nowhere.

The film is easier to follow than most Iranian imports. Good as they are--and they're generally quite good--they still tend to drop the Western viewer right into the center of a plot without much preparation. Since this is a road picture, we get more of a chance to catch our bearings. And though it's simpler than the common Iranian film, Kandahar is complex enough--it's not a standard story of heroism. Our heroine is a little anti-heroic--arrogant, standoffish. She's a persistent foreigner as an Easterner might see one: a tourist unable to adapt herself to the situation. She distances herself from her experiences by recording them (she's making a tape for her sister).

This tape reflects the director's gleanings, his ideas and his poetry. Makhmalbaf captures the misrule and perversity of the Taliban: next to which the perversity and misrule of even the Iranian government looks almost reasoned. Made before Sept. 11, the film serves today less as anti-Taliban propaganda and more as the introduction to the work of one of the world's most impressive new film directors.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

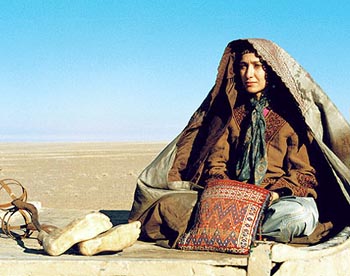

Far From Home: Nelofer Pazira plays a woman who must journey to Afghanistan to save her sister in 'Kandahar.'

Kandahar (Unrated; 85 min.), directed and written by Mohsen Makhmalbaf, photography by Ebrahim Ghafori and starring Nelofer Pazira and Hassan Tantai, opens Friday at the Towne Theater in San Jose and the Aquarius in Palo Alto.

From the January 10-16, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.