![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Nailing Them to the Wall: Construction consultant Glen Strong, who is also an arbitrator for the contractors state licensing board, says quality in new-home construction is slipping because of inferior materials and the use of inexperienced, inadequately trained workers. 'If you have four or five years of experience standing next to someone with a skill saw, you can get a license,' he says. 'You don't even need the pickup truck and the dog.'

Stucco Shock

What do you do when your brand-new dream house starts falling apart at the beams? As hundreds of homeowners in the valley will tell you: Scream as loud as you want. Nobody will hear you.

By Jim Rendon

INSIDE A NEWLY MINTED $600,000 home in the Evergreen foothills, Kenneth Chin wields a three-foot-long level as if it were a broadsword, slashing at his walls and floor, pointing at the staircase.

"Unacceptable. This is absolutely unacceptable," he says loudly, over and over, invoking his own sort of victim's mantra. Charging up the stairs, he stops and pauses for a moment. "This one will blow your mind," he says, dropping to the floor, level in hand.

With the level placed on the virgin, cream-colored carpet, Chin watches the tiny air bubble slide to the tip of the little glass tube and bounce gingerly at the end. "Go ahead, walk on it," Chin says, motioning with his hand. The floor rises in a surprising slope.

Around the corner, another wall is so askew that the door frame meets the wall at the floor but is more than an inch away at the top. Chin has a long list of problems and complaints about how the builder, Lion Estates, has handled his situation.

Though the home is only 8 months old, the ceiling over his entryway sags, many walls are out of plumb, the driveway is cracked. He says both the cable and phone wiring were faulty, roof tiles are obviously misnailed, roof trim is improperly joined, many boards are split, and poorly hammered nails dangle next to roofing supports. A splash guard is missing on one bathroom sink. The seams between drywall panels are visible through the plaster and paint. Nail heads can be seen in the trim. Expansion cuts in the driveway are marked but remain uncut.

"I'm sure that this is just the tip of the iceberg," Chin says, fearful of what defects may lie beneath his warped walls.

TEN MILES AWAY, off Blossom Hill Road in Almaden Valley, Gertrude Beck looks hopelessly at the frenetically cracked stucco facade of her half-a-million-dollar home. When it rains, water pours into her living room through the window sill and earthworms crawl under the gap between the threshold and the front door. Her neighbor, Chris Parry, watched in horror as a bathtub full of water emptied down the drain and, thanks to an improperly joined pipe, directly into the subfloor of his brand-new home. There are thousands more like them throughout Silicon Valley: owners of new homes struggling to get builders to fix problems, everything from minor headaches to life-threatening structural flaws.

Last year, the San Jose district office of the Contractor's State Licensing Board received 1,045 complaints about construction quality in the valley. That's roughly one complaint for every seven housing units built here every year.

Mark Lazzarini, president of the South Bay Home Builder's Association, says that statewide, 70 percent to 80 percent of all townhouses and condominiums become the subject of lawsuits. Many of this valley's best-known builders have let problems slide to the point that homeowners have been forced to sue.

Anderson Homes, William Lyon, Pinn Brothers, the Mission Peak Company, Warmington Associates, New Cities Development and others have all been dragged into court by angry homeowners here.

Kaufman and Broad, the nation's largest homebuilder, which reported a net profit of $95 million in 1998, has been sued again and again in courts across the western United States. Locally the company faces three multimillion-dollar suits brought by groups of homeowners--one in Hollister and two in San Jose--and many smaller suits. Kaufman and Broad also has the dubious distinction of being the only home builder in the country to be under an order from the Federal Trade Commission to handle defect problems in a timely manner. It subsequently broke that order in 1991 and was fined $595,000.

One Kaufman and Broad homeowner in Mountain View is still angry with the company over problems with a home she bought in 1997. Fearing for the value of her home, she asked that Metro not use her name. She says that the roof over her porch was not completed and it took the company 11 months to get around to fixing it. In order to get her oven to fit in the kitchen, workers removed and discarded the heat shield. Many windows leak, the gutters and down spouts all leak. Her door locks were broken for four months.

"If I had other choices I never would have bought a Kaufman and Broad home," she says. Unfortunately, many of the other choices are not much better.

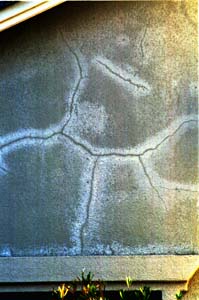

Not What It Was Cracked Up to Be: When the stucco on Gertrude Beck's new Almaden Valley home started to shatter, the builder offered to fix it by covering the outside of her house with an elastic paint, which she refused.

IN 1979, ELIZABETH DOLE gave a speech to the home builder's association in Las Vegas. In it, the then head of the Federal Trade Commission and now former Republican presidential candidate warned of a consumer revolt. Construction defects in new homes were among the top consumer complaints in the country, Dole said. In a surprising turn, Dole, herself a small-government advocate, called on the building industry to clean up their mess or else, she threatened, the federal government would be forced to start regulating the industry.

With the exception of the Kaufman and Broad case, the FTC has kept its regulatory influence off the industry. But little has changed. Today everyone from the Home Builders Association to homeowner groups say there is a big problem. In California, it is worse than in many places.

In 1998, 124,035 new housing permits were granted in California. The Contractors' State Licensing Board received 26,076 complaints. Arizona permitted about half as many homes, but the Arizona Registrar of Contractors received only 7,700 complaints: one quarter of the number received in California, half California's complaint rate.

Nonetheless, the home-building industry is booming. In 1995, the state approved permits for 83,864 new housing units. In just three years, that number increased by 50 percent. In Santa Clara County, the number of new housing units more than doubled, from 3,401 in 1995 to 7,574 a year later. That number has yet to fall off significantly.

This extended building boom is at the core of what has gone wrong with California's construction industry.

Because skilled contractors are spread too thin, much of the work on new homes is performed by people who are not qualified, says Glen Strong, president of Sea Hawk Enterprises, a construction-consulting and project-management firm. Strong is also an arbitrator for the Contractor's State Licensing Board, where he helps to settle disputes between builders and homeowners. "It's a simple matter to obtain a contractor's license," he says. "If you have four or five years of experience standing next to someone with a skill saw, you can get a license. You don't even need the pickup truck and the dog."

Strong says many contractors take on jobs above their level of expertise because the money is good and the demand is so high. Few builders have the kind of training that most had just a generation ago. Many union tradesmen, who go through rigorous training, are passed over for cheaper unskilled labor. "Today people get their training from whoever they stood next to on the scaffold," Strong says.

Another problem is the quality of timber. When this valley was first developed, the wood came from the Santa Cruz Mountains. Most houses built as recently as the 1950s were constructed with dense old-growth lumber that was properly dried before it was used.

Now, most old-growth trees have been cut. Remaining are young, fast-growing soft-wood trees. The wood is not as dense. And it is green, making it softer and easier to work with. But that also means that it dries and shrinks once it is in the structure. It can warp and bow. Strong says that builders expect the wood to shrink about 5/8 of an inch for each floor. In a two-story home, that is an inch and a quarter, the kind of gap that can cause a lot of problems.

Amal Sinha, San Jose's chief building official, says that the International Conference of Building Officials now requires beams in structures to be closer together. The wood that is used today cannot support as much weight as timber from just a generation ago, he says.

All this is topped off with a peculiar problem: the notion that bigger is better.

When the tract home was invented, it was a one-story rectangle with two doors and a handful of windows. A 1,200-square-foot home was the norm. Now, most tract homes are two stories. Many have cathedral ceilings, picture windows, multi-car garages, decks and skylights. A 4,000-square-foot tract home is hardly unusual in this valley of personal palaces.

Complex designs call for skilled labor, and open the door to more error. "Any place where you penetrate the building envelope [like with a window, a deck or a door] you need a professional craftsman. Most builders use casual labor," Strong says.

Assuming the best intentions on the part of builders, that leaves plenty of room for mistakes. And if a builder makes mistakes, homeowners must rely on the contractor's good will to get those problems fixed.

GERTRUDE BECK, a widowed senior citizen, and her two adult daughters, Jennifer and Lisa, have spent years pleading, cajoling and obtaining legal orders in an attempt to force their builder, New Cities Development, to fix problems with their half-million-dollar Almaden home.

Just months after the Becks moved into their new home, a large crack appeared in the living room. It ran up one wall, crossed the ceiling and ran all the way to the floor on the other side of the room. Where Beck had a plasterboard wall and a crack, the model home had an exposed wood beam, a difference that concerned her more and more as the crack continued to grow.

When Beck told NCD about the problem, the developer inspected the property but refused to fix anything. Less than a year after purchasing their home, the Becks were forced to hire an engineer to look at the house in order to determine why the crack was spreading. What he told them terrified the Becks. The roof rafters had not been properly attached to the walls--a situation which Beck says left the house totally unstable.

But this was not enough to convince the developer to act. The Becks were forced to hire a second engineer at their own expense. Only after more inspections and long negotiations did NCD agree to fix the problem. So much was wrong that it took an NCD construction crew 10 hours to properly attach the roof to the rest of her home, she says.

The Becks are not the only NCD homeowners who have had trouble with the company.

Chris Parry, who watched 50 gallons of water drain from his bathtub into his subfloor, says he eventually got NCD to repair the damage and replace his water-stained furniture, but it was not easy.

"We went through three years of hassles fighting over this," Parry says. "They did not do anything for us when the problem happened, but when I started writing to the district attorney's office and the Contractor State Licensing Board, their attitude started to change."

But that doesn't mean all Parry's problems have been fixed. Parry says that his shower pan has cracked four times, and that NCD only replaces the pan without looking for the root of the problem. When builders addressed the mold-damaged vinyl, the company just laid the new vinyl over the old, trapping all the moisture inside and making the mold worse, he says.

Since most of Parry's problems stem from the water leak, something that was easy to identify, he says he has been able to get NCD to act. The Becks, however, were not so lucky.

While the ceiling crack was spreading across the interior of her home, the outside of Beck's home was beginning to crumble. By the time NCD fixed her roof, the outside of Beck's home was well on its way to becoming a jigsaw puzzle of winding cracks.

Looking at the fissures that still mar the surface of her house, Gertrude Beck wonders how workmanship can be so bad. Every window and vent, every intrusion into the wall of the building has multiple cracks leading in every direction.

"How can someone do a job like this and still be able to work?" Gertrude Beck asks.

In January of 1995, the Becks sent a request to NCD asking them to replace the stucco. They sent another letter in February and another in March.

NCD finally offered to put elastameric paint on the stucco. It would stop any water intrusion from the cracks, company officials told Beck. And it would cover the unsightly mess that her home had become. At the time NCD was still working on new phases of the development, and a cracked monster like the Beck home was hardly a selling point.

NCD, like every developer, knows that cracking stucco is not unusual. In fact, all stucco cracks to some degree, says John Bucholtz, one of the country's leading experts on the substance and the 20-year publisher of a bimonthly construction industry newsletter. But that is no excuse for the condition of Beck's house. He says that her cracks may be due to poorly applied stucco, but are more likely related to structural problems with the frame or foundation of her home. He says 95 percent of the elastameric paints on the market, particularly the cheap ones, are no good. And if the best ones are not applied properly, they will only bubble and peel off.

Beck's neighbor and others in the tract who had similar cracking problems opted to let the builder use the elasticized paint. Over the fence from Beck's home, her neighbor's cracks are still visible through the cheery orange paint. Up close, hairline fractures crisscross the wall, like veins beneath the rubbery skin.

Beck refused the paint, and repeated her simple request: start over and do the job right.

NCD refused.

All the while Beck found more and more problems. Water leaked in through the downstairs windows, the front doors did not close properly. And the limestone tile on the kitchen floor began cracking.

"They [NCD] saw three women and the treated us like dummies," Beck says.

Beck encountered so many problems and so much resistance from NCD that she finally got fed up and made a sign reading "NCD sold us a lemon," and planted it in her improperly graded front yard.

This finally drew a response from San Jose's planning department. She got a letter from the code enforcement division telling her that if she did not remove the sign, she would be fined $2,500 day.

BECK COULD NOT BELIEVE that the planning department was threatening her while ignoring NCD, which had erected a house riddled with problems. Beck called the planning department many times to find out how her home, with so many defects and deviations from the plan, could have been approved. She was hoping to find some help in the city's office; after all, she says, they do enforce the building code.

But Amal Sinha, San Jose's chief building official, says his department does not work that way. "We enforce the code," he says. "But the primary responsibility falls on the designer. They are the ones who have the responsibility to design a safe structure that complies with the codes and regulations."

The city checks those plans. Inspectors periodically check up on contractors throughout the construction process of every home. But the building department, he says, is not in the policing business.

Building inspectors work with contractors to ensure that structures are built according to plan and up to code. Sinha explains that the Uniform Building Code and other regulations are just the basic, bare minimum required by law for health and safety. Much of what the department does is ensure that builders adhere to the plans. They check to make sure that plumbing does not leak, that pipes and electrical wires are not too close together, that fire doors are installed properly, even that the right street number appears on the home.

But there is much that inspectors do not look at, like whether doors lock, or walls are perfectly straight, or that the paint job is done correctly. The department is not a consumer affairs division, Sinha says.

Nonetheless, homeowners like Beck and Chin are outraged that their homes passed inspection. They feel that the city should be liable in some way for letting defects and in some cases code violations slide by.

Sinha refused to comment directly on any specific homes, citing concerns about ongoing or future lawsuits. He even points out that by law his agency cannot be held liable for any defects that his inspectors miss. If inspectors miss a major defect, it is the consumer's responsibility, not the department's, to get the problem fixed.

Houses are large and complex, with thousands of components. If a builder really wants to break the code, he will probably find a way to, Sinha says.

"It is impossible to go from page 1 to 60 and catch all of the things in a plan," he says. And though inspections are thorough, a half-hour inspection of a 4,000-square-foot house can only cover so much, he admits.

"In any profession, you find good and bad people. Some professions are more inefficient, unethical and careless," he says. "The challenge for them is to provide training and focus on the work. They must take pride in their work."

For an industry that is all about tangibility, it is ironic that even the public guardians say that the production of quality homes relies on something as unenforceable and ethereal as pride.

And pride is the one thing that many critics say is missing from the industry today. Anything with four walls and a roof will sell in San Jose. And many quality issues buried beneath the drywall or the floor only surface years after a purchase. Glen Strong laughs when asked how long houses are meant to last today. "Well, the implied warranty is for 10 years," he says.

JENNIFER BECK, Gertrude's daughter, has a half-inch-thick file with notes from her conversation with officials from the California State Licensing Board. Each sheet represents a phone call, she says. Beck, like thousands of other local homeowners, has gone to the board for help in resolving disputes with her builder. Despite the time and energy she put into working with this state agency, no resolution was ever reached. In fact every homeowner contacted for this story who contacted the board found only frustration.

In cases it tries to resolve, the board can ask an independent investigator like Strong to go look at a home and determine what the builder should fix. Strong says that as an inspector for the board, he can comment only on complaints made by the homeowner. If he inspects a home for the board and finds additional problems not mentioned in the complaint, he cannot even let the homeowner know they exist, let alone require the builder to fix them.

But the Becks never even got that far. Jennifer Beck says that after months of conversations state representatives dropped her case without ever inspecting her home.

According to Lynette Blumhardt, a spokesperson for the board, about 40 percent of the complaints that her agency gets are resolved through mediation. If contractors refuse repairs, they risk losing their license. But most large home builders have multiple licenses, and none of the major builders investigated for this story had ever had their license suspended or revoked for a construction-quality dispute, even those that had lost lawsuits over construction-quality issues.

In the end, a revoked license does nothing to help a homeowner to get things fixed.

It is just that problem which pushed Arizona to create a multimillion-dollar recovery fund. The account, funded by annual contractor license fees, compensates homeowners who win judgments against contractors who still refuse to fix the problem. In the last year, the fund has given out $2,836,049 to 456 Arizona homeowners.

California has nothing like this fund.

And though Blumhardt insists that her agency provides an effective service for homeowners, even industry representatives are skeptical of the licensing board's resolution process.

"In California, the only way to settle a defect problem is by filing a lawsuit," says Lazzarini, president of the Home Builder's Association.

Photograph by George Sakkestad

BY JULY OF 1996, the Becks had run out of options. Their home was crumbling around them; the builder was totally unresponsive. They say they had only one option left: the courtroom.

The women hired an attorney and had a construction consultant do an analysis of the home. Construction Management Associates of Santa Clara prepared a 45-page report detailing the building's shortcomings. The company found 34 problems with the house, including 18 violations of the Uniform Building Code. Omar Hindiyeh, president of CMA, found additional problems with the roof system. The stucco was thinner than the minimum code requirements. Plywood sheathing was missing from the chimney. Numerous problems with the wire mesh and tar paper that provide the support and weatherproofing under the stucco were discovered. Some of the electrical work was out of compliance with the National Electrical Code.

In his introduction to the report, Hindiyeh writes, "During our inspection we discovered a number of construction defects which are code, health and life-safety issues, and can lead to premature deterioration of building systems. ... This inspection was limited in scope, and should not be relied on as representing an exhaustive study of the property."

After working with one attorney they did not like, the Becks found Ralph Swanson at the San Jose firm Berliner Cohen. Swanson says that the case went to the doorstep of a jury trial before he was able to arrange a settlement.

The Becks received $8,000. And the parties agreed to hire a neutral consultant who would evaluate some of the most contentious issues, particularly the stucco problem, to decide how NCD would fix those problems. The neutral consultant would also supervise the work.

Gertrude and her daughters say they did not want to settle, but were pressured into the agreement by Swanson. They also say that last-minute changes were made to the agreement that they were not aware of at the time they signed it.

They are concerned that the agreement does not require NCD to bring the building up to code. And instead of the neutral just consulting on the most contentious issues, they say they now need to pay for half of the cost of reevaluating the entire house--something they have already paid for more than once.

The Becks never even got their settlement money. Beck says Swanson made them sign the check over to him before they left the courthouse.

That settlement was reached a year ago. The Becks have not authorized any payment to the inspector. NCD has not fixed a single thing. The Becks say that NCD has gone back on their agreement to begin repairs. NCD president Lee Newell says he is waiting for the Becks to act.

Swanson refused to discuss details of the dispute over the settlement agreement, but he says he got a good deal for his clients, that the builder agreed to fix virtually all the problems in the house, an estimated $80,000 worth of repairs.

The Becks say that the court system, their last and most expensive hope, has also failed them. They spent $30,000 on Swanson and another $30,000 on reports, experts and other attorneys, money that is gone forever. Even if they took their case to trial and won, they could not win punitive damages or attorney fees from the builder.

Even attorneys admit that the court system can be a disaster for someone like the Becks.

"Homeowners suffer a horrible delay getting their case to trial," says attorney Paul Monzione, an attorney who has handled many construction-defect cases. "General contractors bring in the subcontractors. The litigation grows to huge proportions. All the subcontractors fight among themselves. Lawyers who charge by the hour benefit and experts benefit and homeowners sit there with their single biggest investment crumbling around them. There is no easy way out."

Many homeowners sue in groups to help defray the costs. And he adds that in the end, many homeowners do well in court. But in a case like Beck's, where they are the only ones with such severe unattended problems, the cost of the suit may have been better spent just fixing the house on their own.

BUILDERS HAVE LITTLE to lose if they choose to ignore defects in their homes, particularly in a housing boom. Builders often offer cheap quick fixes that do not get at the root of the problem. Rather than turn their homes into a battleground, many people opt for the quick fix and hope to sell before the problem resurfaces.

Gary Daniel, one of Monzione's clients in Morgan Hill, says that Warmington Homes was more than willing to spackle over a wall that was out of plumb. But in the wake of a terrible spackle job, the company refused to tear out the wall and put it up properly. And they have never tried to fix the mud slide behind his home.

No one expects a perfect home. But what many do expect is for builders to be willing to repair their mistakes. And more than anything it is the unresponsive and arrogant attitude of many contractors that angers homeowners. Most of the contractors were not much better when approached for this story.

Jerry Chen, general manager of Lion Estates, who built Kenneth Chin's Evergreen home, was one of the most responsive. Unlike some developers, Chen was willing to listen to the list of problems. Many, he says, are easy to fix. Others, he promised to look into. Though he was willing to listen, Chen says that some buyers have unrealistic expectations for their homes, even if they do cost more than a half-million dollars. Chin, he says, is a little "picky."

Amy Friend, director of public relations for Kaufman and Broad, says that 90 percent of all Kaufman and Broad home buyers are happy with their homes. "We take a lot of pride in the homes we build," she says, adding that, unlike most companies, Kaufman and Broad offers a 10-year warranty. She would not comment specifically on the FTC consent order, but says that the company has changed since the 1970s. At no time in the conversation did she admit that any Kaufman and Broad homes had any legitimate defects that the company refused to repair.

Newell, president of New Cities Development, has little to say about the Becks' trouble. "I've built over 5,000 units and never had a problem," he says, echoing Kaufman and Broad. To the company's credit, one homeowner says that NCD happily fixed numerous small problems in her home. But when Newell was asked about other homeowners who had complaints, he got short. "That's all I want to say, thank you," he said, and hung up.

Standing on the cracking limestone tiles in her kitchen, Gertrude Beck says she is angry, and afraid that her home is losing all of its value.

"Sometimes I feel so bad I want to give up," Beck says, stalling out at the end of a long-winded rant about criminal builders, corrupt attorneys and incompetent public servants. "My children say, 'Mom, you're going to kill yourself.' But someone has to bring this out. Someone has to stand up against this."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Fissure Price: A network of cracks started appearing in the stucco of the Almaden Valley home owned by Gertrude Beck shortly after she bought it. She has currently spent $60,000 of her own money trying to rectify this and other problems.

Fissure Price: A network of cracks started appearing in the stucco of the Almaden Valley home owned by Gertrude Beck shortly after she bought it. She has currently spent $60,000 of her own money trying to rectify this and other problems.

Unfair and Unsquare: Gary Daniel says uneven lines in his home made him suspect he had gotten a crooked deal, but carrying a level around the house confirmed it.

Unfair and Unsquare: Gary Daniel says uneven lines in his home made him suspect he had gotten a crooked deal, but carrying a level around the house confirmed it.

From the January 13-19, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.