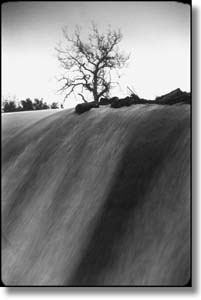

Feral Faucet: Water rushed through Los Gatos Creek following recent rains, illustrating the effective flood control maintained by the Santa Clara Valley Water District. But the district, as a recent report shows, has internal problems which may demand a different kind of engineering.

Photo by Christopher Gardner

An independent investigation of the Santa Clara Valley Water District has left the $1 billion agency that controls our water supply choking on complaints about racism, incompetence and waste. One employee likened the culture to a Dilbert comic strip, but it's doubtful even Dilbert would tolerate this.

By Michael Learmonth

As flood waters coursed through the Central Valley, uprooting 150,000 people and causing an estimated $1.6 billion in damage, the agency responsible for keeping Silicon Valley flood-free was sitting pretty. Reservoirs in the county were full, but not spilling. The Guadalupe River was swollen, but not destructive.

So good was the news at last week's board meeting of the Santa Clara Valley Water District that the board moved on to other business, namely, deciding to notify the press that Silicon Valley's water supply was safe from the contaminated Delta floodwaters.

But the gentlemanly tenor of the board meeting (the only female member, Rosemary Kamei, left early) belies the findings of an internal study, obtained by Metro, which reveals a startlingly different picture of the $1 billion agency. Employees claim the agency tolerates racial taunting of its employees, wastes public funds, promotes unproductive workers and avoids financial accountability in its capital budget.

Conducted between February and December 1996 by the San Jose management-consulting firm Young & Associates, the study summarizes the results of one-on-one interviews, a questionnaire and anonymous written comments submitted by water district employees.

One employee wrote that district workers at the Vasona pump station posted a photograph of themselves dressed in Ku Klux Klan garb. Another reported a supervisor whose favorite joke at meetings was to tell African Americans on his staff how many "coons" he killed on the way to work. A third wrote that a Latino was told to work on bricks "because that's all Mexicans know how to do."

Of the 288 employees surveyed, only 18 percent thought their managers were capable of handling racial discrimination and sexual harassment situations. A scant 24 percent believed communication from their managers was "open and honest."

Almost two-thirds reported problems related to job performance, and only 30 percent believed that good work is recognized and rewarded by management.

In their comments, many expressed thanks and relief to finally have a chance to tell their stories. Some challenged the board of directors to act because they believed their concerns would be ignored by district staff.

A number of comments, transcribed verbatim in the study, addressed theft and the abuse of flex time by managers who employees say come to work late and leave early.

"Supervisors don't report sick leave when taken. Workers see them doing it, and it filters down."

One employee wrote about major instances of theft from the machine shop, as well as ordering new parts to resell or take for personal use. Another complained about employees "conducting private business during working hours."

Many wrote that promotions are often given to the incompetent. "There is the issue of being accepted or ignored or even rewarded by promotions," wrote one employee. Others thought incompetent workers are more often kicked upstairs with a promotion instead of fired from the district.

"I feel like I work for one of those Dilbert organizations," stated one employee.

The district, overseen by a seven-member board, provides wholesale drinking water to local water companies and maintains county rivers and streams, assuring that heavy rains bring no floods and long droughts bring no thirst. The district assesses taxes in the county based on the amount of flood-control dollars spent on a particular region. It is the third-largest government bureaucracy in the county, with more than 600 employees, a budget of $151,745,871 for this fiscal year and cash reserves of more than $330 million.

The report comes on the heels of a restructuring effort begun in 1994, now headed by General Manager Stan Williams. An attorney who came to the district from a water utility in Tulsa, Williams was hired to bring accountability to the district, which doubled its staff between 1984 and 1994. He explained the rationale for the restructuring in an internal newsletter: "Our previous approach--while perhaps not explicitly stated--was to undertake new programs and expand staff accordingly in a 'whatever it takes' fashion. The result was that in seven years, the district's budget for salaries doubled."

The battle to bring accountability to the district was complicated by the lack of any long-term financial planning document that clearly accounted for money spent from start to completion and included maintenance. Sources say this ad-hoc style of financial planning resulted in unaccounted-for expenses and projects that never seemed to end. Even today the draft Capital Improvement Program is vague on where the money is coming from for specific projects. "It is basically a one-sided plan," says Richard Nakagawa, a former district budget analyst. "They basically put out a wish list as far as what they want to spend." Everything the district builds, it must also maintain "in perpetuity." For example, in 1998 the district should complete the Guadalupe River project at a cost of $139 million, but that, like all others, will have to be maintained forever.

In 1993 Ilse Eng, a young budget analyst and former employee of General Electric, began work on the Capital Improvement Program. Part of her job was to obtain from managers very specific information about the purpose of their project, the amount of money already spent and the projected spending until the work was to be completed.

But according to Eng, she immediately met with resistance. The old-guard engineers were reluctant to give up fiefdoms and subject their projects to greater financial scrutiny. The conflict took the shape of the classic political division at the district: the builders versus the bean counters.

"Engineers did not take my numbers seriously," Eng recalls. "My intent was to make that document go public."

Soon, she came out with a draft of a five-year plan.

"The engineers went crazy when I showed it. I broke out salaries and benefits for each department," she says. "There were so many hidden numbers in that budget."

Resistance to her work, she says, came in passive and aggressive forms. Engineers were late with their numbers and project summaries. A few took her to lunch and asked her to stop work on the budget. One even joked, "Are we going to have to break Ilse's legs?"

Eng was distraught. She researched the budget requirements of the district. In the past, she says, the absence of a long-term plan encouraged fudging and shuffling money between projects. She believed a stringent Capital Improvement Program was both appropriate and ethical.

She went to Williams, who, she believed "deep down, was trying to do the right thing."

"Nobody wants to do this," she remembers telling Williams, a handsome, graying attorney who had just become general manager. "What do you think?"

First Williams asked where the antagonism was coming from. Then he returned the question, "Do you think it's the right thing to do?"

In the meantime Eng was honored by Williams with an Exemplary Performance Award for her work on the 1995 budget, which won national recognition from the Government Finance Officers Association. The board of directors also lauded Eng for her budget reforms.

Eng took maternity leave from the district starting in July 1995. By the time she returned in November, she discovered that her position in the finance department had been moved to administration beneath an engineer. Gone were her computer, her files, her staff.

"It was sabotage," says Eng. "I was forced out."

Today Eng is happily back in private industry, where she says budget hawks are rewarded, not thwarted.

For 40 years, the water district adhered staunchly to two prime directives: get water and stop floods. But in the last two decades, changing environmental laws and an increased public-awareness campaign have pushed the district to a broader mission. Environmentalists often find themselves at odds with the district's direction. The most obvious current example is the Guadalupe River Project, the third and final phase of which could be blocked by a lawsuit filed this month by the Guadalupe/Coyote Creek Conservation District unless the construction plan can be modified to accommodate a run of Chinook Salmon that spawns in its waters.

In the meantime, a study conducted by the district last year of Santa Clara County residents ranked protecting the environment a greater concern than flood control. Board members and district engineers frequently chalk up results like this to public ignorance. Their response is to step up public information to remind the public that flood control and drought management are yearly cycles requiring constant maintenance and public money.

Young & Associates' organizational culture survey included recommendations for the water district that stopped nothing short of rethinking everything. The 17-point list concludes that immediate action should be taken to review district goals, past grievances, recent promotions and salaries. Young & Associates suggest they perform another survey of district employees in 12 to 18 months to check progress.

Eng thinks it will take more than tinkering to save the derelict ship.

"There is a powerful force in that district," she recalls. "A lot of unethical things go around. You have to do the popular thing, not the right thing."

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)