![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Mayhem in Miniature

The true-crime dioramas of the Nutshell Studies scale murder down to dollhouse size

By Sara Bir

REDUCTION can make life more manageable, but it also magnifies it into something deceptively less compact and dense. Replicating our world in dollhouse scale is generally thought of as a trifling pastime for little girls and frou-frou hobbyists, but some gigantic issues lurk behind its cloak of preciousness: control, omniscience, ownership.

Some 60 years ago, a dogmatic and eccentric woman named Frances Glessner Lee subverted these relationships by painstakingly constructing dioramas of grisly crime scenes. She called them the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, and she made them to be used as forensic training tools. Though Lee constructed the Nutshell Studies—18 dioramas, all in 1:12 scale—between the 1940s and 1950s, photographer Corinne May Botz has made the Nutshells available to the public for the first time in her book The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death (Monacelli Press; $35), a fascinating and oftentimes perversely maddening collection that seamlessly juxtaposes scholarly rumination with haunting, storybook-gone-wrong images.

In filming a documentary about women who collect dollhouses, Botz learned of the Nutshell Studies, which are currently housed at the Baltimore medical examiner's office. She became captivated by their creator. Lee was born to a well-to-do Chicago family in 1878, and grew up to find that her independent, knowledge-seeking disposition suited neither the times nor her parents' notions about what women should be. Through a failed marriage and an adulthood of financial dependency on her parents, Lee cultivated a desire to be of consequence in a man's world, a goal she eventually fulfilled by replicating composites of real-life homicide scenes in tiny scale.

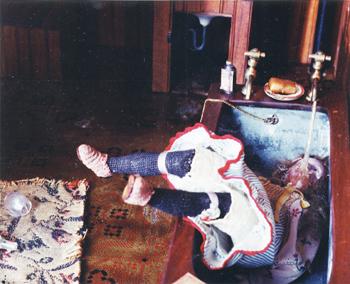

Lee's Nutshells overlook nothing: the pencils write, the calendars are accurate to the dates of the crimes, the patterns of blood on walls match bullet entry wounds. Each study took months to complete, as Lee knitted pinky-length stockings with safety pins and painted the bisque bodies of corpses to reflect the state of decomposition they were in at the time of discovery. A middle-aged husband hangs from the rafters of a barn; a prostitute lies stabbed in the closet of a stuffy rooming house; a murdered family of three transform what would otherwise be a scene of everyday domestic harmony.

Lee insisted that the studies were not whodunits. "They are," she once wrote, "designed as exercises in observing and evaluating indirect evidence, especially that which may have medical importance." Lee involved herself in legal medicine, and in 1945 founded a series of weeklong seminars at Harvard, holding sessions centered on observation of the Nutshells.

The dioramas are still used in forensic training today, and their gory magnetism remains extremely powerful. Botz's photographs, with their blurry patches and darkened corners, add another layer of narrative to the hazy, sordid stories the Nutshells tell us. Botz does not show us the dioramas straight-on, but only selected patches of them. Just as in a real-life crime scene, much of what we need to know to understand the whole picture is missing.

But that's what makes the Nutshells so engrossing—there's something hopeless and incomplete about them that painfully mirrors reality. "The photographs in this book are curiously unlike the models," Botz notes. "I am surprised each time I visit them. Like a person, the Nutshells appear to be continuously changing—becoming more fragile, smaller, slightly larger, more obviously dead. My photographs simultaneously moved the models further from and closer to their source—the crime-scene photographs that guided their creation."

Botz presents the Nutshells on a case-by-case basis, with line diagrams that allow us all to play detective, only to come up scratching our heads. Botz's photographs are so tangible and immediate that their ultimate distance from us is maddening. The result is a curious composite of coffee-table book, feminist biography and true-crime novel—deceptively childlike, decidedly adult and disquietingly enduring.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Tub Thumper: One of Frances Glessner Lee's doomed dolls ends up down for the count.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the January 19-25, 2005 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.