![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

The Complete Errol Morris Interview

Geoffrey Dunn interviews Errol Morris, director of the new documentary 'The Fog of War'

Morris: How are you?

Morris: I'm fine.

Morris: Cambridge, Massachusetts

Morris: Well, let's see what we can accomplish.

Morris: Aww!

Morris: That's commendable.

Morris: OK.

Morris: Yes.

Morris: There's the book and, of course, the phenomenon of the book. When the book came out it was a bestseller; it was reviewed, and beyond the reviews, there were many editorials, articles, commentaries. And very quickly, the book came to be described as McNamara's apology--his mea culpa. And having read the book, the book seemed to me very different in character. It wasn't an apology. It was a tortured examination of his past, that was far more interesting. When I think of an apology I think of someone saying, I'm sorry, and then someone else can decide whether to accept the apology or not ...

Morris: ... I accept your apology, I don't accept your apology. This is something actually far more interesting.

Morris: No.

Morris: Yes. I have seen a tape, and I do know about it.

Morris: I do.

Morris: That's correct.

Morris: I probably said it, and it's also true.

Morris: You do!

Morris: Yes.

Morris: Well, I read all three of the books, because that was followed by Argument Without End and then Wilson's Ghost in 2001. My first meeting with McNamara was in May of 2001.

Morris: Long before 9/11 ...

Morris: And I believe McNamara agreed to an interview because, whether this is true or not, I think it most likely is true: He saw this as part of the publicity for the new book. He had been on a book tour, and he really came up here expecting to talk about Wilson's Ghost at length. But of course the thing became something quite different.

Morris: That's correct.

Morris: I don't think so by that point. He had called me a couple of days before coming up, telling me ostensibly that he was going to cancel the interview, and he went on at some length, and then at the end he said, 'But I agreed to come up, so I will.' And he--I mean this is very, very characteristic of McNamara in general--he limited the amount of time and his commitment, and of course, that got extended.

Dunn: How long was the actual interview?

Morris: The interview was supposed to be no more than an hour. And he stayed for about three hours on the first day, and then he came back a second day on a Wednesday--a Tuesday and a Wednesday, and we did another three hours on that second day.

Morris: In this instance, it's just the two cameras: the primary camera on McNamara and the camera on me.

Morris: And there's a half-silvered mirror across the camera lens with my image on it, and I'm also looking into a similar arrangement.

Morris: Aw!

Morris: Oh!

Morris: Probably a result of the fact that I made less of an effort to hide them.

Morris: I would say, pretty much the same as in the past.

Morris: I shot approximately six hours, and then he came back later--much later--and we did more. He came up three times, and then we also went down to Washington and just recorded audio, which you hear at the very end of the film.

Morris: That's correct. And I continue to talk to him. In fact, he was up here today. So, even though the movie is finished, I still carry on this dialogue. And you know, he's concerned with the DVD, what's going to be on the DVD and so forth.

Morris: Indeed he is.

Morris: You know, his response is also complex. I mean, he likes the film, he has complained to me about the epilogue, which he does not like. And he has complained to me about the lessons, which he does not like.

Morris: Well, no. He has his own lessons. He wished they had been explicitly his lessons rather than my lessons.

Morris: Or my lessons as abstracted from things that he says in the film. And ...

Morris: No. Not at all.

Morris: Or in Wilson's Ghost. But many of the scenes of the book are in the movie. I mean, I don't explicitly label every lesson. And my lessons are somewhat more pessimistic and ironic than his lessons. I mean, they all turn back on themselves, if you like. And the 11th lesson even suggests the possibility that the previous 10 are meaningless.

Morris: I would say, yes.

Morris: Well, I think he's always been tortured.

Morris: I don't think that that's on the occasion of the distribution of the movie.

Morris: You know it's hard to know. My guess is that he was not tortured in the way he is today.

Morris: Oh, I think much earlier than that.

Morris: I do.

Morris: Because. well, one question that you asked that I didn't really finish answering is this question about his feelings towards the film and his feelings towards the responses to the film. I actually believe that he is interested in communicating these lessons--these issues--to, you know, the current generation, that if he's really unhappy about something, it's how the movie inevitably--and maybe this is just part of the McNamara phenomenon itself--the movie inevitably, for people who lived through the war, becomes about him, about how he is a bad man. And there was a Talk of the Town piece, just published this week in The New Yorker ...

Morris: And, yeah, why doesn't anybody actually respond to the content of what he's saying? You know, I like to remind people that it isn't one or the other. In fact, I think that part of the movie is this response, you know, Who is McNamara? What right does he have to speak to us? On the other hand, I feel that his stories, whether it's of the Cuban Missile Crisis or the firebombing of Tokyo, or the Gulf of Tonkin, are very, very important and relevant stories that have enormous bearing on what is going on today. And it probably would make sense to talk about these issues in that context. Everybody wants to prove that he is evil.

Morris: Well, maybe that's a little bit hyperbole, so I apologize.

Morris: Well, he's a great writer.

Morris: Tell me!

Morris: Doesn't matter.

He changes, as you know, during the course of the war, right?

Morris: Yes.

Morris: And he denies it.

Morris: It's a profound change. It's why I'm sympathetic to McNamara. You know, I came into this film like most people, you know, who demonstrated against the war in the '60s and early '70s, having an idea of McNamara as the chief architect of the war, McNamara as the "bad guy," McNamara who is responsible for this mess, and over the last couple of years I've come to know him, and I have spent a lot of time researching ...

Morris: ... this material. I mean, I find it really quite interesting because I've been involved in corresponding to two writers on the Net who wrote about this film--Eric Alterman in The Nation, and--it hasn't been published yet--Fred Kaplan in MSN Slate.

Morris: Yes, MSN Slate.

Morris: Oh no. I haven't sent in a reply.

Morris: I wrote a very extensive reply to that piece. And what interests me, of course, is that people are so convinced that they know the history of this man that they can't even admit of the possibility that there may be evidence to the contrary of what they believe--in some cases, recent evidence--recent in the sense that it's become available recently, and that the story of Vietnam becomes a far sadder story. I think that people in general like to figure out who's to blame, as if you can pinpoint one person who's responsible for it all, you're going to be in really great shape.

Morris: And McNamara's own lesson, "Empathize with your enemy," may apply to him as well. For whatever reason, I'm more interested in understanding him than condemning him, and I have no reason--take my word for it--well, don't take my word for it ...

Morris: Thank you. I don't feel any differently about the war than I did 40 years ago.

Morris: I think that the war appalling. I still think it's appalling. What I'm interested in is how McNamara sees himself in that history, against bits and pieces of evidence that I've strewn through the movie, whether it's memos or voice recordings.

Morris: Very powerful. And Alterman is a great example. Although he would love to pull rank, "I am a historian,"--as if somehow that has anything whatsoever to do with evidence--the actual puzzle of McNamara saying to Kennedy that he wants out of Vietnam and becomes part of this plan to remove a thousand advisers by the end of the year, and the rest by '65, presumably after the 1964 election. And then hearing Johnson chastise McNamara on the phone. I've watched, most recently the HBO film Path to War. I've watched sort of endless recitations of this formula: Johnson didn't know what to do. McNamara pushed him into war. Well, I'm terribly sorry. I do not get that impression from listening to the voice recordings and reading the documents.

Morris: Well, I don't think you can read the Pentagon Papers. It's like reading, you know, an encyclopedia. I mean, it's a reference book.

Morris: Do I make use of them? Do I refer to them constantly? Yes.

Morris: OK.

Morris: Correct.

Morris: It was not in a rough cut. There was so much stuff that could not end up in the movie.

Morris: I feel fortunate that we have a movie that. ... Is it a perfect movie? No. Are there things that are omitted that should be in it? Yes.

Morris: I don't think that it was--in thinking about it, I don't think it was expressed in enough detail and in an interesting enough way.

Morris: Oh, yeah.

Morris: I mean, it's pretty clear [that] by 1966 and certainly by 1967 that McNamara is voicing considerable concern about the war, and McNamara points out that it was that Nov. 1, 1967, memo that essentially got him fired by Johnson.

Morris: Yes.

Morris: But it comes from not knowing whether if you write a memo such as that ... I asked him, actually, this morning...

Morris: [I asked him,] When you wrote that memo, what did you think was going to happen? Did you think that Johnson was going to change his policies? Did you think that Johnson was going to just simply remove you from office? He said he didn't expect to be fired.

Morris: I think he was fired. I don't think the memo was written by way of quitting. He wrote the memo because he disagreed with Johnson's policies and felt that he could not continue, but it was still with the idea that it could... McNamara said something very, very, you know, I've heard this so recently, I haven't said anything about this to anyone but yourself--

Morris: An exclusive, indeed. That he said, and I think it's a very powerful thing--he said to me that he's not the chief architect of the war. It's just simply wrong, but he can be faulted for not struggling enough with Johnson to stop it. And so that he does fault himself.

Morris: That's correct. He does.

Morris: I have some idea, although, in truth, he's never talked about it in detail with me. I have met one of his children--his youngest child, Craig. I know that there must have been terrible stresses and strains in that family. He had three children who were, essentially, antiwar activists, and a wife who didn't believe in the war, either.

Morris: Well, actually that's another thing that he takes issue with.

Morris: ... because he believes, in fact, that it did benefit his family. It benefited all of them.

Morris: I think the tears were about the fact that it was horribly painful and horribly difficult.

Morris: I have come to like him, and I ... and I am moved by him.

Morris: On the other hand, you know, I know that some people expect him to get down on one knee and beg forgiveness.

Morris: I mean, if the idea of expecting McNamara to get down on his knees and beg forgiveness for his sins from the American public is what people have in mind, this is just not going to happen.

Morris: I think people--I've asked them--like when they say that he hasn't gone far enough. it takes various forms. He hasn't gone far enough, he hasn't been forthcoming enough, he hasn't gone all the way. I'm not sure what people expect.

Morris: Yeah.

Morris: Well, I have asked him. I ask him at the very end, of course, the question, Why didn't you speak out against the war in '68, when he left the administration.

Morris: And, God, it's complex

Morris: Unfortunately, I am going to Italy in a couple of hours, and I have the Denver Post that I'm supposed to speak to, so I'm supposed to keep doing this ...

Morris: I'm sorry we have to stop here...

Morris: I'm going way South. I'm going to Sicily. I'm shooting some commercials in Sicily for the next week and a half.

Morris: Sure.

Morris: Yes.

Morris: Well, I have all of those black-and-white photographs interposed with graphs ...

Morris: I did.

Morris: I decided not to use it; I decided to use those still photographs instead.

Morris: Because the movie, you know, in some sense, is from his perspective, and oddly enough he does not talk--he talks about the terrible tragedy for the Vietnamese people, but he doesn't quite talk about it the same way as he talks about the firebombing. I did include ...

Morris: And perhaps it was because I liked the footage so much. I can't really tell you why. I don't think that I had some kind of devious intent, but someone mentioned to me that the bombing was so much more abstract in Japan and become so much more real in Vietnam, and I liked that--that was intentional. And I like the photographs. Maybe I would have edited those photographs slightly differently. But I like the effect that they have in the Vietnam sequence.

Morris: No.

Morris: Although I have, you know, listened to him, and talked to him, but the final control rested with me.

Morris: Yes.

Morris: You know, he argues, and I argue back and eventually we'd come to an agreement. There's nothing that I put in the film that he has not been able to live with, however.

Morris: Indeed!

Morris: Well, thank you very much.

Morris: Well, thank you very much.

Morris: OK. Take care ...

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

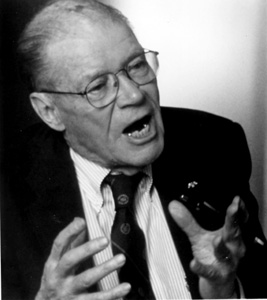

Robert McNamara.

Dunn: Hello, this is Geoffrey Dunn in California.

Dunn: Good, how are you?

Dunn: Where are you?

Dunn: Thanks very much for taking the time. I'm assuming we have about 15 minutes.

Dunn: You tell me. All right. I want to make sure about some facts. I've read a lot about the film, a lot of it off the Internet, and I just want to make sure I have the basics right, because I don't want to trust anything off of there.

Dunn: No, I just want to be sure.

Dunn: Well, I don't know if it is or not, but I have some issues with the film, and I want be sure I have things right.

Dunn: A couple of interviews I read said that what prompted you to do the film was that you had read Robert McNamara's book In Retrospect.

Dunn: I'm curious, what about the book prompted you to take the next step?

Dunn: Right, sure ...

Dunn: Did you see McNamara's presentation at Harvard after the book came out?

Dunn: Have you ever seen a tape of that or know about it?

Dunn: Oh, you do. OK. So you saw there was an incident; there was a moment when a vet came up and said, "You still haven't understood the pain ..." and McNamara yells at him to shut up. Do you remember that?

Dunn: It's an interesting thing. I read another interview that you gave in which you said that, you know, there are people who never are going to forgive McNamara.

Dunn: And that ...

Dunn: It's true. Well, it was good for me to read before I went to see the film. I see McNamara as a complex figure. I teach a class on the Vietnam war on film at the University of California.

Dunn: Yes. And you know what? It's tough to crack that film lineup and this one's probably going to crack it. So it forced me to go into the film with an open mind. But in the back of my head, I still heard McNamara yelling at that vet to shut up. That arrogance. That hubris. And you got beyond that, obviously. And so I'm trying to probe at your sense of him as a man. So anyway, you obviously read the book and experienced the phenomenon of the book.

Dunn: And you contacted McNamara. I'm curious what his ...

Dunn: Oh! OK, so ...

Dunn: A ha. I understand that, but ...

Dunn: So, when you contacted him, it was after or during the Wilson's Ghost book tour?

Dunn: So, when he came up to do the interview, was he viewing the interview in that context?

Dunn: So you did six hours of him in the studio, and how many cameras do you have running as part of your apparatus there?

Dunn: That's interesting to know, because I never quite understood how it worked, but I do now. It basically is looking into--right at the camera lens. Right?

Dunn: Got it. So, I've seen all your films except Vernon, Florida.

Dunn: And I'm an admirer of sorts. I actually also teach a class on documentary film, and I use The Thin Blue Line.

Dunn: It's been interesting to see the way students change perspective with the film over the years, but that's a whole other conversation. But there are more jump cuts in the interviews in this film than any of your other films. I'm curious what that was a result of.

Dunn: I understand that one. So probably no more than in the past.

Dunn: Gotcha. OK. So anyway, you do the interview and he actually gives you--so you shot six hours, or he was there six hours?

Dunn: Yeah, so that was just an audio. That's when you pressed him on the other questions, and you have the B-roll of him driving.

Dunn: I'm sure he is. He seems like a detail-oriented man.

Dunn: Since we're on this subject, let me ask, what's his response been to the film?

Dunn: What do you mean? The way they're presented?

Dunn: I see.

Dunn: So they don't exactly parallel the lessons in In Retrospect?

Dunn: Yeah.

Dunn: I thought that, too. Very interesting. OK. Well, there's been national response to the film, and there will be more of a response to the film. Has McNamara been offended by any of the reviews or things that have been written?

Dunn: I mean is he tortured again?

Dunn: Yes?

Dunn: Well, was he--you say he's always tortured--I've never met him, but I have read a lot about him, been a student of the war and sort of fascinated by him. One of the things I was fascinated about was him as a West Coast guy--San Francisco Irish boy ... grows up in the East Bay, so I have a whole different hit on that, being a West Coast Irish boy, with San Francisco Irish roots. And do you think he was tortured up until he got to the Pentagon? Do you think he was tortured at Ford.

Dunn: OK. that's my assumption too. I sense he comes out of World War II not very tortured about the firebombings, goes to Ford and then becomes tortured, beginning around 1965.

Dunn: So you do?

Dunn: OK. From the first trips.

Dunn: I read it; I read Roger Angell's piece, whom I do know.

Dunn: Hm. OK, well, I don't think I want to prove that, so I don't know that everybody wants to prove that ...

Dunn: No, no, no. Look, I understand the phenomenon now. And it was after reading Roger's piece last night. I know him through baseball.

Dunn: He's a great writer, and he's a great baseball writer, but I've had issues with his baseball stuff. What got to me--I was born in '55, OK? Lost a cousin in Vietnam, Vietnam becomes an overwhelming experience for me in my youth, OK? I mean, I grew up watching it on TV. I'm younger than you, so from the time I'm 5, I'm watching it on TV. OK, the assassination happens when I'm 8. It helps to form my life. World War II--I've never experienced the firebombings. My wife is 7 years younger than I, born in '62. Vietnam is not really a part of her upbringing. She and I had a very different response to the film. And it's what you were just getting at. It's that this is fresh and new to her. The McNamara in the film that she watches is different than my McNamara. And then, I was fascinated by the World War II stuff, because I didn't have any buy-in to it. It was new and fresh for me, startling and shocking. I knew about his role from Halberstam's portrayal, but not--I had never heard him talk about it, etc. So it was very different. So I understand the phenomenon you're talking about. I actually have a theory about documentary construction ...

Dunn: Whether it be film or photography, and it has to do with the relationship with the constructed document--your film--with the audience. We all bring different baggage in our interpretation or engagement or assessment or evaluation, and you as a documentary--I know you as a nonfiction filmmaker...

Dunn: I know, 'cause with me, they're both of equal value--I love them both. You can't control what we bring to the project, to that process. And you know, in The Thin Blue Line or any of your other films, people aren't bringing the kind of baggage about the subject that we are to this film, you know? Fast, Cheap, and Out-of-control--I didn't know any of those characters, so I'm not bringing any baggage to my interpretation or evaluation or assessment of them, right? And so with this film, the audience is bringing a variety of carry-on with them. So that's probably what is happening there. And I can't divorce my feelings about McNamara, and I don't view him as one of the evil forces in Vietnam, and I guess that gets to an interesting point.

Dunn: Profoundly. And he doesn't want any knowledge of that change in the film. And you ask him about it.

Dunn: Right! What about that? What was your response to that?

Dunn: Sure.

Dunn: But I saw it referenced somewhere--the Kaplan piece.

Dunn: OK. So it's published on ...

Dunn: No, I read--yeah, I read that piece, too.

Dunn: Hmm.

Dunn: No, I am take it. Look, I'm taking your word for it, and I find--for me, this is an interesting process on my end to get to a place of integrity, so I take your word for it; I sense that's what you were doing. And I think it's a beautiful thing, by the way, to do that.

Dunn: I see that.

Dunn: They were fascinating, by the way. The audio tapes were amazing.

Dunn: I don't either. I have a sense that--I mean, I think McNamara's a guy who falls on his sword in all this, OK? So, you're talking to someone who has a different view, not out to get McNamara, but nonetheless, you know, because you've been through the documents, if you've been through the large compilation of the Pentagon Papers, even the smaller New York Times one. I don't know how much of it you read.

Dunn: Well, you can read the Pentagon Papers, because I have.

Dunn: Yes. OK, then you're reading them, I assume, so I don't want to get lost in that.

Dunn: It's not the Odyssey. You can read through the Pentagon Papers, reference them, or whatever, and you see in them McNamara's concerns raised, you see his doubts. He commissioned them.

Dunn: Why didn't that come out in the film that he commissioned the papers? Did it come up? Was it in a rough cut?

Dunn: I know. I know that.

Dunn: There are a zillion things. I know that. I also do film, so I know that, but my question is, to me, his role in literally forcing that collection to be put together. I'm just curious why that wasn't in there. You made a choice.

Dunn: So you brought it up. I got it.

Dunn: I know that answer, then. That makes sense to me.

Dunn: Although he says he wasn't sure if he was fired or not.

Dunn: Still ...

Dunn: Yes?

Dunn: But of course he was fired. And he still refuses to accept that. He's been in denial for 30-odd years and he's still in denial.

Dunn: An exclusive!

Dunn: OK, that seemed pretty honest to me. I'm curious then, because I keep thinking about the concluding segment of the film, where--and remind me, I'm assuming that this was in a subsequent audio interview that you did with him--where he says he doesn't want to talk about Vietnam any more, and then he also--and correct me if I'm wrong here--he also says something about not wanting to talk about the impacts on his family.

Dunn: OK. And I presume you know the impacts on the family.

Dunn: You know, he cries two times in the film, and one of them is when he says that you know, being in D.C., taking that position benefited his family. And you can see there that he knows that's not the case. And the pain of that ...

Dunn: Yeah?

Dunn: Wow--boy! What do you think those tears were about, then?

Dunn: Yeah. I felt hugely empathetic to him there.

Dunn: Yes, I see that.

Dunn: Come on. I'm certainly not expecting...

Dunn: I don't think that's what I meant by going all the way.

Dunn: I guess I expect answers to some of the questions about Vietnam that he refused to talk about.

Dunn: And for me, if I could interview him, I would ask him why he didn't go public in '67.

Dunn: Yeah.

Dunn: Yeah, I think that's the complexity for -- about --

Dunn: OK, you know I'm grateful to your time.

Dunn: No, no, I understand. -- I'm Irish / Italian -- my family's from the North. Where are you going?

Dunn: Well, it's beautiful down there, too. Beautiful. Let me just ask one last question, then.

Dunn: Your choice of B-roll. Particularly around the bombing in Vietnam. It's largely from the perspective, looking down, of the U.S. bombers.

Dunn: Which is the perspective, perhaps of the technicians in D.C. I'm curious if you thought about using impacts at the ground level. Faces of the Vietnamese ...

Dunn: That's from--right, I--but how about footage? Did you think about that?

Dunn: And?

Dunn: And I'm just curious why.

Dunn: Right. I noticed a difference.

Dunn: OK. Did you have any arrangement or agreement with McNamara?

Dunn: So, he did the interview, and you could use it how you wanted?

Dunn: Did he see rough cuts?

Dunn: Was there anything he demanded be pulled out or ...

Dunn: OK. Well, that's the other thing about documentaries--they take on a life of their own.

Dunn: You've unleashed a new life here ...

Dunn: And well, thank you for discussing this with me. We'll probably--I have some issues as is obvious from my questioning here, and I guess it's not so much with some of the facts, but just his refusal--all the way is the wrong metaphor--his refusal to go further into reflection on some of these issues, and that's what I find profoundly irritating to me. That's all. I appreciate the integrity that you took going into the film, and with all your films and in this discussion, so I'm grateful for that.

Dunn: And thank you. Have a safe trip.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

Web extra to the January 22-28, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.