![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Deadbeat Club

Looking for ways to balance the state budget? Try tapping the cheats who refuse to pay taxes.

By Najeeb Hasan

JOHN BARRETT gets a kick out of nabbing the bad guys. In fact, he's so enthusiastic about his job that in his spare time he keeps busy by scanning criminal activity lists such as the one titled the "Dirty Dozen." And so, two Fridays ago, Barrett couldn't contain his excitement--there was a bust planned for the following Monday, and Barrett, providing things went down as planned, wanted the world to know about it.

Admittedly, Barrett's job description isn't too sexy: He's not involved in any undercover investigations into international drug cartels. He doesn't rely on oily informants for crucial tidbits. He doesn't really even need a gun.

Rather, at California's Franchise Tax Board in Sacramento, Barrett and his co-workers are responsible for the relatively dry task of every year sifting through 160 million income records--from banks, the Internal Revenue Service, employers and other sources. The data is compared with the income records reported on tax returns. A discrepancy might lead to a good bust.

But the vast majority of the 600,000 improper tax notices the Tax Board sends out turn out to be innocuous mistakes. The "Dirty Dozen," however ominous sounding it may be, is the annual IRS list of only the most common tax scams, a list that includes descriptions of offshore transactions, identity theft and frivolous arguments.

"That's my favorite," Barrett reveals happily. "They come up with any argument they could find for not paying taxes."

Sure enough, that Monday, Jona Lona, a 47-year-old Watsonville mechanic, and Corrina Lona, a 42-year-old San Jose prepaid telephone-card hawker, surrendered themselves to authorities at the San Benito County Jail in Hollister. No car chase, no SWAT team, no shootout, just a low-key self-surrender. A three-year Tax Board investigation concluded that the Lonas had earned $1.2 million in unreported income and owed the state about $300,000 in unpaid taxes, penalties and other costs.

Until their arrest, the Lonas resided in a $1.1. million, 43,000-square-foot home on five acres in Hollister, complete with some 15 palm trees. Parked in their driveway were a 2000 Jaguar, a 2000 BMW, a 2001 GMC Sierra and a 2002 Porsche Carrera. The couple also owned two pieces of rental property in Hollister. Not too shabby for a mechanic and a telephone-card wholesaler.

The alleged crime, explains Barrett, was not all that sophisticated. Corrina Lona was the main breadwinner in the family and the member of the family who didn't file any taxes. The cars and the property were all in her husband's name, but the real money was earned through her job in San Jose.

"She would sell those prepaid phone cards to places like 7-Elevens and liquor stores," Barrett explains. "When she would go in and pick up the payment, they would pay her in cash, and she would end up pocketing the money. I would say that she was stealing from her boss. He was paying her well, and she was taking the money."

Wasteful Excesses

Though the concept of evading taxes is as old as the concept of taxes itself, what's new is the understanding that tax evasion has a significant impact on the economy, noteworthy enough for state Controller Steve Westly to make inquiries into holding public hearings on what's known as the cash, or underground, economy.

With California's budget crisis triggering journalists of all stripes to write story after story about the wasteful excesses of public servants--the unneeded new office furniture, the state-paid cell phone bills, the gourmet dinners charged on government-issued credit cards, the grossly inflated salaries for part-time appointed positions--the missing stories are how members of the private sector, either individuals or businesses, bypass the system and, in effect, victimize the average taxpayer as much as, if not more than, the prodigal politician.

And so, for every Manny Diaz, the California assemblyman notorious for his taste in taxpayer-subsidized SUVs, there are at least 10 deadbeats like Douglas Denardi, a 45-year-old Saratoga man sentenced to two years in prison for tax evasion days after the Lonas were booked and released on bail.

The self-employed Denardi pleaded no contest last May to four felony counts of failing to file state income tax returns. He had earned more than $1.4 million in unreported income and still owes the state $216,000 in unpaid taxes and had, perhaps wisely, opted to skip a sentencing date a month ago.

In a recent report published for Congress by the Taxpayer Advocate Service, an overseer organization of the IRS, the figure for the total estimated tax gap attributed to noncompliant taxpayers was given as $310.6 billion. (The tax gap is defined as the difference between total earned income and total income reported.)

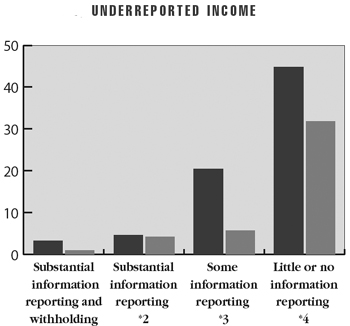

A further breakdown of the numbers shows $30.1 billion was lost because people failed to file tax returns, $248.8 billion was lost to underreporting income and $31.8 billion was lost to underpaid taxes (see chart). In effect, the IRS concludes that a full 15 percent of taxpayers are noncompliant, though not necessarily criminals. Tax fraud or evasion by individuals, as opposed to corporations, is overwhelmingly responsible for the tax gap, especially from incomes based on easily concealed cash transactions. One expert guesses that if all lost taxes were collected in California--an unrealistic expectation--that the state's budget would be balanced.

Joe Fitz of the state's Board of Equalization estimates tax revenues are lost to the state in a number of ways. For example, Fitz studied the tax impact of Internet and mail order sales and concluded that in 2001, California lost $1.2 billion because consumers were unaware they had to pay California sales tax on out-of-state goods. In another study prepared by Fitz, he estimated that California lost $292 million in one fiscal year to cigarette-tax evasion alone.

Meanwhile, San Jose Budget Director Larry Lisenbee discounts the thought that national figures provided by the Taxpayer Advocate Service have much effect on local economies. "I don't get that sense," Lisenbee says. "In most of our biggest revenue categories, it's pretty hard to avoid paying taxes. If you avoid paying property taxes, we will get your property. In respect to sales tax, we do have that one leak [out-of-state Internet and mail order sales]. Technically, they're supposed to report that and pay tax, but nobody does. There are people here who are undoubtedly not paying business tax, but that's one of our minor revenue streams."

Lisenbee's thoughts are repeated by an official from the Santa Clara County assessor's office. "It's such a big picture level," the official says. "It's such a high level that it's hard to see how it trickles down to us. The county really has no direct way to show it. You're dealing with that which you don't know."

Joseph Bankman, a Stanford law professor who is a national expert on the cash economy, disagrees. Bankman points out that, despite the national outrage about corporate tax shelters, it's the nation's small businesses that hurt the economy more.

"We're in a funny position in our society," Bankman says. "The fact of the matter is that if you go to the average small business that's a local little restaurant, that's a dry cleaner, that's a retail store, on average, the underreporting rate is very high. As much as half of the cash income that comes in small businesses isn't reported."

Those small amounts probably won't make the average tax cheat wealthy, Bankman says, but it does leave a sizable gash in the state's revenue stream. "People like me have certainly railed against corporate tax shelters. But the corporate sector can't hide tax. There's no tax shelter that's really quite as efficient as putting 20 dollars in your pocket and not reporting it."

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Darker bar = Underreporting tax gap ($B). Lighter bar = Net misreporting percentage (%).

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the January 22-28, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.