![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Yosemite Slam

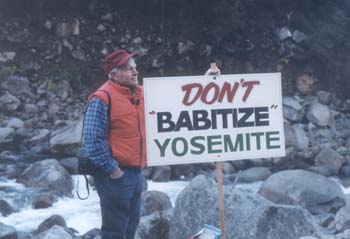

Christopher Gardner Sign Language: Northern California environmentalists say Yosemite park management is putting the needs of oversize tour buses ahead of the park's plants and animals. These critics have stepped up efforts to solicit public input on the park's Valley Plan by the Feb. 1 deadline. A small group of Silicon Valley activists protests the dynamiting of a Yosemite road, which they say will kill bats, trees and other native species By Cecily Barnes REMNANTS OF THE WEEKEND still clutter Joyce Eden's blue Toyota Camry, parked in the driveway of her Cupertino home. Amid the sleeping bag, flashlights, cookie packages and ground cover, only a single sign--which reads "Stop the Destruction"--suggests that the trip was anything more than a relaxing visit. In fact, Eden's weekend was far from a vacation. On this trip to Yosemite National Park, she and 60 other environmentalists, including members of the Sierra Club, Friends of Yosemite Valley and the Green Party of California, stood in the snow to convince park management to stop dynamiting and bulldozing a 7.5-mile stretch of the El Portal Road leading into the park. Eden has taken six months off from her job teaching vegetarian cooking to dedicate her days and nights to heading up the local chapter of the Sierra Club's Yosemite Committee. Since returning home, she has been making phone calls, holding meetings and strategy sessions, and investigating legal means to halt the bulldozers that rumble into the night under the glare of halogen lights. If her attempts fails, the historic El-Portal Road, which winds into Yosemite National Park between the mountains and the Merced River, will be widened by up to 7 feet in certain spots, crushing the burrows of wild animals and destroying the Merced River's virgin riparian habitat. "There's no place to widen it," Eden explains about the road, which abuts a canyon wall on one side and a cliff that drops down to the river on the other. "They're dynamiting the uphill slopes on one side and building out to the river bank on the other. Widening this road is destroying the river." Since construction has already begun--it's nearly four months into what is estimated to be a two-year project--Eden says there's no time to lose. Eden says the park skirted the need for an environmental impact statement by opting instead for a less stringent "Environmental Assessment," a document made public after the Sierra Club requested it via the Freedom of Information Act three weeks ago. The area along the Merced River, Eden adds, has been federally designated as "wild and scenic," a designationwhich she believes should afford it extra protection. In addition, Eden and other environmentalists believe the entire road-widening project has been a rush job to make quick use of federal flood funds--money that was initially intended to repair flood damage, not widen roads for tour buses or improve amenities at the lodge. Eden was heavily involved last October when the Sierra Club won an injunction halting a planned lodge expansion using the same federal funds. The lawsuit resulted in the intervention of Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, who forced the park to come up with a comprehensive Valley Plan, scheduled for completion at year's end. Eden and others are frantically trying to meet a Feb. 1 deadline for public input on what should and should not be included in the Valley Plan. (The proposed plan can be viewed and commented on through the park's website.) The Valley Plan looms on Eden's horizon as a bigger battle--one that will determine the future of the national park: Will it undergo a wonderful restoration or a woeful commercialization? "This is going to determine what happens in Yosemite for the next 30 to 40 years," she says. When Eden finally rests her voice, after 70 minutes explaining the dangers facing Yosemite, her disheveled Cupertino headquarters seem remarkably clean given the extremity of the battle she's been waging. And the importance of the dog-eared paperback copy of John Muir's My First Summer in the Sierras becomes clear: For Joyce Eden, it is her inspiration and her Bible.

Bigger Is Better WITH MANY AN "AH YES," Scott Gediman, Yosemite's jocular public information spokesman, acknowledges the familiar environmentalist complaints against the El Portal Road/Highway 140 widening project. He's heard them all before. Why did the park duck the environmental impact statement, opting instead for a less stringent environmental assessment? What possibly justifies bulldozing along the Merced River, which has been federally designated as "wild and scenic"? What about the animals? Well-worn responses on each of these matters slip easily from Gediman's mouth, each arguing the same basic premise: Experts have shown this project won't hurt the environment. In fact, a wider road carries a host of benefits. Now, behemoth tour buses can barely stay on their side of El Portal Road (studies have shown, he says, that buses cross the center road divide 22 times on average); the expansion will make the road safer for these vehicles. And whereas the existing guard wall has weakened from age (it was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the late 1930s and is eligible for the historic registry), the new wall will meet modern crash standards. And contrary to what environmentalists say, a stable road will actually protect the river. "It's eliminating sections of road from literally falling in the river, which has happened before," Gediman says. These are the official responses. When pressed, however, Gediman acknowledges that Yosemite's plants and animals will pay the price for a wider road. "Obviously, there's an impact with dynamite being used," he admits. "But when they're done with their revegetative efforts and with the stabilization of the road, [the road] will be away from the [river] corridor." Trees will be sacrificed to the road, he admits. At best guess, Gediman speculates that 50 will fall, not counting those trees too young to actually be called trees. And yes, some might be up to 200 years old. "No one's denying that there could be trees up to that age being removed, but we're removing as few as we can," he says. "We don't have any specific numbers." And then there are the eight rare species of bats which environmentalists insist are hibernating in the mountain range and will be buried beneath the rubble as the dynamite explodes. On this matter, Gediman holds up his hands. The park's experts could not say for sure if bats hibernate in these spots. They might, but just as likely they might not. "The experts said it's not known for sure if they're hibernating there," Gediman concludes. During the bats' breeding season, he adds, construction workers will refrain from dynamiting. According to Gediman, experts also have found that the dynamite use and other construction practices will have no significant impact on the five threatened and endangered animals identified in the area: the peregrine falcon, the bald eagle, the California red-legged frog, the elderberry longhorn beetle and the Central Valley steelhead. And when the road is extended out toward the river, Gediman says, the plan is to use a woven mesh of steel beams topped with tar to support the road, not "fill" materials. But in the end Gediman acknowledges that, of course, some impacts will be felt. This, however, is all part of the delicate balance that park representatives must strike between preserving the park and providing safe and comfortable access and accommodation for visitors, even those on super-sized buses. Both are within the park's mandate. "The visitor experience is an important fact of the national park," Gediman says. "Buses and RVs are just bigger these days, and we feel it's our responsibility to make that road safe for these vehicles." But Eden and other environmentalists say that catering to the commercial needs of park visitors should be secondary to the park's primary mission of preserving the natural habitat. "They need to fit the vehicles to the road, not the road to the vehicles," Eden says. "This is basically corporate welfare for the tour bus industry. The park itself doesn't benefit because they're destroying habitat." Outside the park itself, signs along the Merced River urge tourists to steer clear of the foliage to support restoration of the river's precious riparian habitat. Eden shakes her head at this irony. "At the same time that the park is trying to restore the riverbank in Yosemite Valley, it is tearing away at seven miles of totally untouched riparian habitat," she says. "It makes no sense. It's planning gone out of control."

Flood Money EDEN WILL BE THE first to admit it: The park keepers who live in Yosemite's modest housing aren't getting rich. Superintendent Stan Albright, the park's highest-paid official, makes $105,000--and the pay scale drops quickly from there. Presumably, Yosemite employees who have given up Jacuzzis and dishwashers have done so out of a genuine love of nature. Given this scenario, Eden can't figure out why these well-intentioned, dedicated people have, in her opinion, totally missed the boat on the El Portal Road expansion project. "We believe in the park service as an important institution and we like to support it, but we can't support their actions on this," Eden says. All she can figure is that when Yosemite came into the windfall of money that followed the 1997 floods, administrators leaped into a spending frenzy. After those floods, rangers meticulously documented every nick of damage and presented Congress with a $176 million price tag. Getting that much was thought to be a long shot. In the history of the National Park Service, the biggest sum ever granted by the government was $50 million to Everglades National Park after Hurricane Andrew. But the Congress opened the floodgate on the nation's bank account and let the coins roll into Yosemite--a total of $211 million. "It's more money than any park had ever seen," Gediman says. "I won't say that other parks were jealous, but it was quite a precedent." Since patchwork repairs had been completed while flood-money requests inched through Washington, the money came to a park that didn't need repairs as much as improvements. El Portal Road was embraced as one of the first projects. "We felt that it was time to fix it and fix it right," Gediman says. But environmentalists argue that the planning and environmental review was rushed and is tragically insufficient. "I think it's a very mistaken project that they've decided to do because they have this money and somebody just came up with an idea for another use for it," Eden says. "It was never in any previous plan, it does not need to be done and it shouldn't be done." Ron Mackie, who worked as a ranger at Yosemite for 37 years, also suspects the project might have been hastened along by the park's bloated bank account--money that could potentially be snatched by the National Park Service. "There's a lot of internal pressure within the National Park Service itself to spend the money," Mackie says. "They're worried they're going to lose it if they don't." At first, Gediman denies that time pressure has anything to do with the park's plans. Later, however, he concedes this point a little. "As time goes on, some other parks might say, 'Hey, they gave Yosemite all this money and they haven't used it--can we get some?' " Gediman admits. "I won't deny that requests are being made. But it's our money." And because the money has been designated for specific Yosemite projects, Gediman adds, very few people would have the authority to reallocate it. Among these would be West Coast regional park director John Reynolds and Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt--the same individuals with whom Eden pleads to stop the destruction. Eden fears that the coveted flood money has placed park superintendent Stan Albright in the terribly tempting situation of pushing through expensive and unnecessary projects just because the opportunity exists. Besides the El Portal Road expansion, dozens of other Yosemite projects jockey for portions of the $211 million. "Yosemite is at greater risk than it has been in 20 years because of this money," Eden says. "They're coming up with plans for this money that are disastrous. There's one plan after another." In a circulated email, Eden urges the public to view the plans and write letters of response before the scoping period ends Feb. 1. Among the points listed in the email: Walk-in camping should be encouraged, bears and other native species should be protected, and cars should be limited rather than laying cement for a new parking lot. Eden also urges the public to write to Sen. Barbara Boxer, their congressperson and Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt. "This is a national park; Yosemite is a world heritage. It's supposed to be safe," she says fervently. Secretary Babbitt has not yet responded to the Sierra Club's letter begging him to halt the bulldozers on El Portal Road. Until a response comes, Eden continues to work in overdrive. At 3pm on Sunday, Eden is not watching the football game or cozying up on her couch with a book; she is recounting the weekend's meetings and preparing for Monday's sessions. The hard work will pay off, she tells me, because it has to. Before parting by phone, Eden remembers something that she meant to say. The words are not her own; they come from Margaret Mead, but Eden believes they were meant to be borrowed. "Never doubt that a small and dedicated group of people can change the world," she recites from memory. "Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has."

For information on how to get involved in the Sierra Club's Yosemite Committee, contact Joyce Eden by phone (408/973-1085) or email (yojo@batnet.com). The Valley Plan guidelines and project plans can be viewed at http://www.nps.gov/yose/planning.htm. Comments can be emailed to YOSE_Valley_Plan@nps.gov. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the January 28-February 3, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Forest Forever: From her Cupertino home, Joyce Eden fights to protect Yosemite National Park. She has sat on the Sierra Club's Yosemite committee for 10 years.

Forest Forever: From her Cupertino home, Joyce Eden fights to protect Yosemite National Park. She has sat on the Sierra Club's Yosemite committee for 10 years.