![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Photograph by Skye Dunlap Dog Daze: Coyote Valley, situated in the southern end of San Jose, was slated for some kind of development in the mid-1980s, through a general plan amendment. But the public is not unanimous in its support for developing the city's last open space as an industrial and residential area. Referen-Dum and Dumber If Florida politicians can ignore registered voters, why not the City of San Jose? City officials say they must throw out the referendum against the Cisco campus in Coyote Valley, even if they have to go to court to do it. By Mary Spicuzza FROM THE BACK, he looked like an environmental activist. A baby boomer in a T-shirt, he hurried through the cellular phone shop in sneakers and shorts in the middle of winter, a baseball cap casually propped over his balding head. The message on his T-shirt virtually eliminated all doubt: a jet black background showing a mini-universe of colorful planets, all of which held signs reading promises like "Future Cisco Site," "Cisco Coming Soon" and "This Spot Reserved for Cisco." Before I could ask him which Coyote Valley preservation group had spawned these corporate conspiracy shirts, the gray-haired shopper spun around to reveal the front-side artwork: the space age creation had been made by none other than Cisco Systems Inc. The message of universal domination on the shirts echoes the resounding confidence that the Internet networking giant and the City of San Jose have maintained throughout the tumultuous drive to build Cisco's $1.3 billion, 688-acre corporate campus in North Coyote Valley. Even after an environmental coalition, People for Livable and Affordable Neighborhoods (PLAN), gathered more than 50,000 signatures for a referendum that would put the project to a vote of the people, determined Cisco spokesman Steve Langdon remained unfazed. "There's some opposition to it," Langdon told reporters in mid-January, "but we're confident we'll ultimately prevail." And sure enough, within days after the stacks of petitions were turned over to the city clerk's office and 40,000 of its signatures were certified for accuracy (a third more than required by law) a pronouncement emanated from the city attorney's office: The petitions were no good. The countless hours spent by community organizers standing in front of shopping malls and supermarkets with clipboards, the signatures, names and addresses provided by 54,423 citizens who wanted a chance to vote on development of the last chunk of open space within the city's limits, were all for naught. A glitch in the wording at the top of the petitions, the city attorney's office reported, had made the signatures of voters moot. On January 16, the San Jose City Council, led by Cisco-supporting mayor Ron Gonzales, voted to throw out the referendum and not put it on the ballot during an upcoming special election. (In April, there will be a vote to fill the council seat vacated by Manny Diaz, who made a move to state Assembly last year. The next municipal election is not slated until March 2002.) Even if Cisco prevailed after an April election, its winter groundbreaking date would have been delayed by anywhere from several months to more than a year. Coyote Valley preservationists first expressed disappointment with the city's actions. Then they decided to sue. While they expected Cisco to try to push its project through, they didn't expect the city itself to override public opinion. "I think it's inappropriate for the body whose decision is being challenged [the city] to be the judge," PLAN attorney Zan Henson says. "It should be on the ballot for the people to decide. The city can file a lawsuit if they chose to." Lawsuit City THE CITY'S MOVE TO TOSS OUT the petitions represents only the latest round of surprises in a project wracked with controversy since Cisco announced plans in the spring of 1999 to develop San Jose's last large piece of open space. The project already faces four separate lawsuits, filed against both Cisco and the City of San Jose by the Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments, the County of Santa Cruz, the City of Salinas, and a coalition of environmentalists from the Loma Prieta Sierra Club and Santa Clara Valley Audobon Society. These suits attack the Environmental Impact Report for the Cisco campus as inadequate, especially in its treatment of traffic congestion, housing shortages, and the regional impacts of such a massive plan. Midway through their petition drive, PLAN activists filed suit against the Internet software giant, accusing Cisco of sending out its own paid pro-project petitioners to illegally interfere with their referendum drive. But pending lawsuits don't stop Cisco from breaking ground, unless plaintiffs also file for a court injunction to prevent development; PLAN members had hoped their referendum drive would, but are now placing their hopes in the courts. Despite rumors that PLAN would be unable to finance a legal challenge to Cisco and the city of San Jose, this week opponents from PLAN publicly announced their intent to file suit against the city for ruling against the referendum. And, according to former planning commissioner Brian Grayson, they have recruited powerful Los Angeles attorney Fredric Woocher to help get the battle to the ballot box.

Park and Parcel: The road leading to Cisco's planned campus could spawn another battle.

Watch Your Language CITY ATTORNEY Richard Doyle says he's not an opponent of democracy, but he expects election law to be followed. "Nobody likes to be in a position of saying that you don't want democratic process to go forward," Doyle says. "But these are substantive problems with the referendum." Doyle can rattle off a laundry list of details with the wording of the environmentalists' petition. He begins with the petition's title, which reads, "Referendum Against an Ordinance Passed by the City Council." "It was a resolution, not an ordinance," Doyle says, referring to the city's agreement to make changes to the North Coyote Valley Campus Industrial Area Master Development Plan. Doyle says that a more significant problem is the ensuing language, which he believes could have misled and confused those who signed the petition against the city. "This referendum is designed to prevent the huge Cisco industrial development project, on the farm lands of Coyote Valley," the petition states. "It wouldn't have that effect," Doyle insists. He says that wording of the referendum would only allow for minor changes to the project, and makes promises that the referendum can't deliver. When asked if he had been in contact with Cisco lawyers about the referendum during the petition process, Doyle says he had to be--Cisco and the city are joint defendants in multiple lawsuits. But he insists that the city made its own decision about the lawsuit, independent of Cisco. Cisco campus opponents say that mixing words like "resolution" and "ordinance" weren't enough to throw San Jose residents into a state of deep confusion over the goals of the petition. "I think it's fair to assume that the people who signed wanted an opportunity to vote on the project," Santa Cruz County Supervisor Mardi Wormhoudt says. "I just don't think that people were that misled. Certainly if 50,000 people signed a petition, they have concerns about the project. It's pretty cavalier of the San Jose City Council to ignore that part of their constituency." If past rulings are any indications, the courts may come down on the side of the people in this fight, particularly since, in this case, the city is attempting to throw out a referendum against itself. People's Court LOS ANGELES-BASED attorney Fredric Woocher, who has spent 20 years arguing court cases over electoral debates, has had an especially busy year. When the Florida ballot mess during the recent presidential election turned into a disaster, national newspapers such as The Washington Post turned to Woocher for guidance. In what can only be called a coup for environmentalists, Woocher, a partner in the prominent Strumwasser and Woocher law firm, has agreed to represent the group in its fight against the city of San Jose. Woocher says that, in general, cities' arguments that referendum language is misleading usually don't hold up in court. The only time a city successfully argued that referendum language was too misleading, he says, involved a case where policy makers were being slammed by petitions; basically, the petitions went beyond changing legislation to personal attacks on policy makers, which is not part of the City of San Jose's argument. "I think in this particular case the city's argument is wrong," Woocher says. City officials argue that they aren't ignoring democracy but protecting it by upholding the law. City Attorney Doyle says that the changes would be so minor that they address mere administrative adjustments, not major legislative changes. Meaning the referendum would only make small shifts in the way the Coyote Valley development is carried out, not stop it altogether. "The resolution is administrative; it deals with density and landscaping," Doyle says. "So it wouldn't have seriously impacted this project." He suggests that a referendum aimed at challenging the development agreement between Cisco and the City of San Jose and the zoning of the project would have been far more successful. He cites those as true "legislative changes." Doyle admits that the situation is unusual, and can't remember another instance where a referendum was kept off the ballot after supporters had gathered enough petitions with signatures. City Clerk's office staff member Nancy Alford agrees, and can't remember when a debate over administrative and legislative changes came into a referendum drive. "I cannot remember a situation when we had enough signatures but they found a reason not to put it on the ballot," Alford says. "I believe that this Cisco one is unique at least in recent history." Diction Friction ZAN HENSON hardly seems like a radical environmentalist. The Carmel Valley-based attorney, who helped law professor Robert Gerard write the referendum, says that the referendum was carefully drafted and, he believes, completely follows the law. "I start with the proposition that anytime you amend the city's general plan or general plan-type documents, you are performing a legislative act," PLAN attorney Zan Henson says. "Why Mr. Doyle would say these general plan agreements are administrative is baffling to me. If these are administrative changes why did the city council have to amend anything?" The allegation that PLAN's referendum would only change the project by 5 percent, a common statistic used by developers' advocates, is bogus, according to Henson. "Whoever said that is blowing smoke," he says. "I'm puzzled and troubled by the city's actions. When we first sued the city to get documents we needed for the referendum, officials said that we could have 30 days to circulate the petition. I thought that was a smart move to avoid delays; now I don't understand why they would want to delay this in the courts for one to two years." Election lawyer Woocher says that often cities try to stall referendums they don't like, but concedes that he hasn't closely reviewed the Coyote Valley development plans. "I haven't reviewed the planning framework, but my initial take is that the adoption or amendment of a master development plan is legislative," Woocher says. "It sets policies and rules for development."

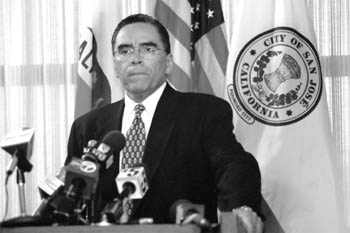

Cis-codependent: Mayor Ron Gonzales has been an early and staunch supporter of the Cisco project since the company announced in the spring of 1999 its plans to build a 20,000-employee campus in Coyote Valley. Petition Politics CRAIG BREON, a PLAN activist and environmental advocate for the Santa Clara Valley Audobon Society, says this latest vote by council is just the newest hurdle the city has tried to create. He says that the City of San Jose has interfered with the referendum drive since its inception. He recalls that PLAN activists had to take the city to court last November in order to receive the necessary documents to craft referendum language, namely the final copies of rezoning plans for North Coyote Valley. "The city clerk's office said they weren't there, and told us to check the planning department. Planning said they were with the clerk. The city attorney's office said it wasn't responsible for providing those documents," Breon laments. "Then in court, the city said they've been available to the public the entire time." PLAN volunteer Brian Grayson adds, "I hate to think that is standard procedure. I don't know why that situation occurred." When Metro called to review copies of the development agreement between the city and Cisco systems on Jan 17, the city clerk's office secretary said she "wasn't sure if they have it in records yet." The records department didn't have it available but transferred calls to the contracts office in City Hall. Staff members in contracts said they were still processing the agreement, but promised to have it available soon. That was three months after the development agreement was signed in October. After obtaining city documents and hiring lawyers to write the referendum, they began gathering signatures of San Jose residents. City Attorney Doyle says that if PLAN members had showed him their petition then, he could have told them of its "serious flaws." But unlike an initiative, which requires approval by the city attorney's office, there is no requirement that referendums be reviewed prior to signature-gathering. Sign Here FROM THE BEGINNING of its signature drive, PLAN also faced swift and strategic opposition from Cisco Systems. Within days of the launch of PLAN's signature drive, the company hired petitioners of its own to staff similar locations, talk to the public and get signatures in support of the Coyote Valley project. "It was extremely confusing to people," Audobon Society's Breon says. "Residents would think they had already signed our petition." Breon adds that while the environmental advocates could only pay $1 per signature gathered, wealthy Cisco doubled--and may have eventually tripled--the amount paid per signature. He says that Cisco increased payments to signature-gathering corporations, which were paying gatherers $2-$3 for each signature by the end of the two-week drive. Breon believes that Cisco allowed anyone to sign, of any age, regardless of whether they were registered voters or residents of the City of San Jose. "I heard from a signature-gatherer that a woman signed on behalf of her unborn child," Breon says. Eric Morley, a local public relations professional hired as spokesperson for Cisco, says that the company gathered 110,351 signatures, all of whom were San Jose residents. When asked if Metro could review the names and addresses of those who signed, Morley refused, saying the petitions are "not public." "It's not like the petition that was formally intended for referendum," Morley says. "We just wanted to provide San Jose residents with information about the project." Morley says he doesn't know how much petition gatherers were paid per signature, or whether they received three times more than anti-development petitioners. "I'd have to get back to you on that," Morley says, quickly adding. "But we are pleased for the overwhelming support for the project." PLAN members, including Audobon's Breon, Sierra Club's Dan Kalb, and former planning commissioner Brian Grayson argue that the number of signatures Cisco gathered reflected their renegade signature-gathering tactics rather than the company's popularity. B. Soffer, a petitioner for the referendum, says that those circulating the pro-Cisco "plebiscite" repeatedly offered jobs to anti-development petitioners, in an affidavit signed on November 30, 2000. Another petitioner, Robert Rooney, says that pro-Cisco employees prevented him from gathering his signatures. "They had one of the petitioners standing in front of me to block, while the other tried to get signatures at a different exit. The petitioner standing by me would speak over me so that I could not be heard," Rooney writes in a Nov. 30 affidavit. "The Cisco petitioners were a big factor in my decision to stop circulating the petition." Cisco's Morley says that Judge Conrad Rushing ruled that the PLAN petition gatherers failed to provide proof of their claims, and found that they lacked merit, whereas Breon says the judge allowed the Cisco gatherers to continue, but never threw out the case. "We gave our petition gatherers instructions not to bother the opponents in any way," Morley adds. Legal Maneuvers OPPONENTS OF THE COYOTE Valley project have had to drop their debate with Cisco to once again focus on battling the City of San Jose. PLAN's Brian Grayson says that the group will have filed its latest lawsuit challenging the city's decision to throw out the referendum by press time, with Woocher as its lead attorney. Grayson says that during his years on the planning commission, he's never witnessed a project quite like this one. "From the very beginning, the mayor [Gonzales] seemed to want to push this through. The planning commission held public meetings, but it's pretty hard to say "public" with a straight face. It really wasn't a public process." He adds, "The way the mayor inserted himself into the process, it seemed very obvious that he wanted to push this project through. I assume the thought was that the new people he appointed [to the planning commission] would take his direction." Project opponents now worry that in court PLAN will face not only city attorneys, but will have to go up against legal research gathered by high-paid Cisco lawyers. Besides feeling that planning decisions were made in private closed-door meetings, development opponents worry that city and Cisco attorneys have been meeting to discuss opposition to the referendum. Joe Guerra, spokesperson for Mayor Ron Gonzales, says that it's no secret that Cisco and city lawyers have been meeting on a regular basis. "We are in the midst of several joint defense lawsuits, and our lawyers are meeting regularly," Guerra says. "Did Cisco and city attorneys talk about the referendum during those meetings? I'm sure they did. Like they might have said, 'Hey, has anybody read the referendum?'" Yet opponents see those meetings as complicating the democratic process more than the mayor's office will admit, and hope that the courts will solve the problem of a city promising to police itself. "The courts take the job of speaking for the electorate very seriously, they have a respect for democracy," Santa Cruz County Supervisor Mardi Wormhoudt says. "Florida not withstanding, they err on the side of the people." Wormhoudt adds that the County of Santa Cruz has no intention of settling in support of Cisco's Coyote Valley project because of its failure to provide onsite housing and strategies now favored by "smart growth" advocates. Fredric Woocher shares Worm- houdt's skepticism that the court will rule the PLAN petition used language that grossly misled voters. "There is nothing misleading about it," Woocher says. "That argument seems extremely makeweight to me." He says that the difference between administrative and legislative changes has held up in court in the past, but his initial opinion is that the changes proposed by PLAN activists use "specific language" to make changes to the Coyote Valley project. "Once it's determined that a change is legislative, it doesn't matter if the city thinks its a big one or a little one," Woocher says. "From somebody who was originally an unbiased observer this smells of somebody coming up with an argument after the fact to try to justify the result they want." He adds, "Unfortunately the powers that be in city governments go to efforts to overturn actions against them." GroundBreaking Democracy THINGS ARE PRETTY QUIET in Coyote Valley these days. Regulars at Coyote Inn and Stage Stop still take refuge from the rain while chatting with beloved bartender Bill Ledin. The shop cat at Coyote Discount Bait and Tackle still laps up attention from south San Jose fishermen who stop at the mother-daughter owned shop for supplies. The field at the corner of Bailey Road and Monterey Highway remains untouched by Coyote Valley Research Park developers. But not for long. "We plan to break ground this winter," Cisco's Morley says. "But of course we will abide by whatever timeline is required by the city." The city says the that there's nothing stopping Cisco from breaking ground now. Joe Guerra of the mayor's offices says, "I would guess the only way that a lawsuit could stop them from moving forward with the project would be a restraining order." Cisco poised, shovel in hand, waiting to break ground has plan critics like former mayor Janet Gray Hayes fearing for the future of Coyote Valley and bemoaning the state of the democratic process in San Jose. "I think it's most unfortunate. We worked a lot on gathering the signatures. It was a real citizens' effort," Hayes says. "A lot of us are extremely concerned that it's too much--too much traffic, too much gridlock, too little housing." Hayes says that she thinks Cisco is a wonderful company, and even owns stock in it, she doesn't think that its massive campus belongs in Coyote Valley. "I was elected mayor as an environmentalist. My slogan was then, and is now, that we must make San Jose better before we make it bigger," Hayes says. "This project won't make it better, just bigger." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the February 1-7, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)