![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Arcana to Arcadia

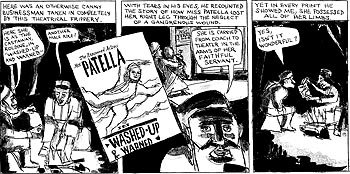

Democratic Urges: In the wilderness of early 19th-century America, every man can afford to be an obsessive. Ben Katchor creates a lost world of New York flimflam men and religious utopians in his new graphic novel IS THE BEAVER a kosher animal? These social, monogamous, hard-working creatures have a sad history of exploitation. Theirs is a legacy of persecution shared by the Jews, as cartoonist Ben Katchor suggests in his new graphic novel, The Jew of New York (Pantheon; $20; 98 pages). One of the main characters is Nathan Koshon, a kosher butcher of New York in 1830. Accused of "willful deception and careless performance of a ritual duty," Koshon flees to the woods, where he is befriended by Moishe Ketzelbourd, a businessman-turned-trapper. When Ketzelbourd discovers that the beaver have almost vanished east of the Rockies, he cracks and becomes possessed of a sort of beaver dybbuk. He goes about on all fours, grieving over empty beaver lodges. Sometimes he's seen splashing his foot in the water--a tragic imitation of the tail-slapping warning sign known to all beavers. Sympathy for the beaver is just one element of Katchor's ambitious story. He has created a work on the lines of Herman Melville's The Confidence Man. Various mystics, flimflam artists and charlatans perfect their hustles. Entrepreneurs and students of religious arcana try to convert one another against the backdrop of the young metropolis. The Jew of New York is full of Katchor's usual obsessions with moribund businesses and deluded middle-aged businessmen. In the author's syndicated strip, Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer (which runs in a number of alternative newspapers), he explores parts of modern-day New York City that have changed little in the last 40 years: the small office buildings of the garment district and elsewhere. These commercial neighborhoods are full of discouraged-looking wholesale companies selling zippers, buttons and whatnots. Their proprietors seem to have been born 50 years old and divorced. These mundane operations become fanciful in Katchor's drawings. Every forlorn building and musty bar has its own strange tale of coincidences, long-lost glory days and bits of fictional trivia. The strip takes some effort to read, though, since the artist's mostly functional drawing style doesn't scan easily. And often, the editors of the papers Katchor works for shrink Julius Knipl down to a tiny space. KATCHOR WAS able to work in a larger size and on better quality paper in The Jew of New York. Here, his skies, which look brown and fuzzy on newsprint, seem more like the ominous clouds and shadows in William Blake's prints. For the first time, you can really see Katchor's characters. Their oversized hats and faces are emblems of brazen confidence as they conduct important, if quixotic, business--such as a plot to carbonize Lake Erie as the source for a soda-water pipeline to Manhattan. Heading the cast of The New York Jew is Major Mordecai Noah, the Zionist who proposes to relocate the Jews to Ararat, a city of refuge on Grand Island across the Niagara River from Buffalo. Hundreds of miles away in New York City, Maynard Daizy, the actor, is preparing to star in an anti-Semitic play, The Jew of New York, which parodies Major Noah. Meanwhile, the famed actress Miss Patella is preparing for her farewell performance. Like Sarah Bernhardt, Miss Patella is one-legged; like Lily Langtry, she is worshipped by a frontiersman--namely, the beaver-fevered Ketzelbourd, who travels with a poster of his beloved diva. The wasting of the virgin wilderness is one of the main themes in The Jew of New York. (The infamous Love Canal is only a mile or so from Noah's haven Grand Island, and the Niagara is said to be one of the most polluted rivers in America.) The devastation of the beaver and the history of Major Noah are both based on true stories--as is the tale of how the beaver was reprieved by the timely change in styles from beaver-skin toppers to silk hats. The Jew of New York is more than just an ecological fable. Like Melville before him, Katchor speculates on how the obsessions of businessmen match the efforts of holy men trying to purify themselves. White whale or brown beaver, the quest for possession that was once the passion of aristocrats becomes democratized--every common man can become a monomaniac. The characters here find the search for a quick fortune every bit as frustrating and elusive as the search for God. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the February 4-10, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.