![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

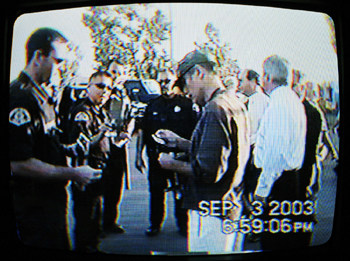

Arrested Development: Police didn't appreciate Joseph Cuviello and other circus protesters demonstrating in the HP Pavilion parking lot. The Caged Birds Sing Circus protesters battle for their free-speech rights in court after arrests at HP Pavilion By Najeeb Hasan HIS LANKY frame folded neatly behind the wheel of his girlfriend's white sedan, Aaron Lodge guides the vehicle south on Second Street in downtown San Jose. He's an attorney by trade--as is his girlfriend, Tracey DeMartini--and he's particularly exhilarated because the two, along with three others, have just sued the city. The case, which hinges on where exactly people can and can't speak freely, has captivated him completely. "Look at [that]!" he exclaims as the vehicle approaches San Jose's federal courthouse. Outside, a dozen or so demonstrators brave both typical San Jose apathy and winter's dreary grayness to wave signs for peace. Lodge enthusiastically honks his support. "First Amendment rights," he observes and then cranes his neck to read the signs. "United Methodists for Peace--oh, that's right, it's the Friday peace rally. See, now they're standing on the sidewalk, so this is classic First Amendment. The security guard is standing right behind them, so maybe that means the courthouse steps are off limits." If his observations sound clinical, perhaps his days as a dead-eyed pool shark coolly surveying the break are coming back to him. Eight years ago, Lodge appeared on Metro's cover as a Santa Cruz man with a pool cue and a dream ("Pool Shark," April 18, 1996). And while that dream proved unattainable, Lodge now looks toward another. In September, Lodge, DeMartini and three others found themselves in an unlikely Western-style showdown with members of HP Pavilion's guest services team. Only instead of pointing guns at each other, the camps were aiming video cameras at each other. The two attorneys had taken part in an annual protest at the Pavilion directed at the Ringling Brothers circus' treatment of its animals. Lodge, along with fellow protesters Deniz Bolbol, Joseph Cuviello and Alfredo Kuba, was cited for trespassing and faced possible fines and jail sentences until charges were dismissed in January. More importantly, the protesters were effectively silenced--though, if Lodge's dream is realized, the silence will prove golden. Animal House In the police reports, Lodge, DeMartini and the others are described as members of the national animal rights group People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. In reality, one member of their group, Kuba, belongs to the organization. DeMartini, who was not arrested, is part of an informal animal rights group out of Redwood City, but neither she nor Lodge really live up to the typical stereotype of the wacky animal rights activist. The Ringling Brothers circus was the first act to perform at the arena after it was erected in 1993, and since then, demonstrators of all stripes have been leafleting the event every year. DeMartini has protested for eight of those years; last September was Lodge's second year. The circus, in fact, has had a poor history in San Jose. In 2001, Ringling made national headlines when a legendary circus trainer was tried for elephant abuse in the city. On the first night of September's show, DeMartini and Lodge gathered with a larger group of protesters congregated on the sidewalk in front of the Pavilion, wearing signs and handing out leaflets about circus animals. Soon after, the couple decided, as they had in previous years without incident, to hand out leaflets at the back entrance of the venue. Walking up the back steps, they noticed a throng of policemen in the back parking lot. To improve its image, Ringling has, in recent years, begun hosting an Animal Open House. In an eight-page color ad taken out last year in the San Francisco Chronicle, an entire page was devoted to the attraction. "I think it is really smart," DeMartini says. "An hour or more before the show starts, they do what I call the pre-show. They take all the elephants off their chains. They put them in a pen. They feed them so people can see them eat and walk around. They have a pen for the tigers to walk around, so people are seeing them kind of in their best conditions. People rarely are going to go down and look at the animals at 3 in the afternoon when they're chained and out of public view. So they go to this Animal Open House." While DeMartini and Lodge were in front of the Pavilion, Kuba, Bolbol and Cuviello leafleted in front of the Open House, which was enclosed in a chain-link fence in the on-site parking lot. People wishing to enter the attraction waited in a line snaking through the parking lot. Kuba, in fact, had paid to park a cargo truck, plastered with pro-animal messages, in the lot. But Ringling parked two large circus vehicles directly alongside Kuba's truck, hiding his message and blocking him in. When Lodge and DeMartini headed toward the commotion, they were confronted immediately by police officers and Pavilion security. Soon after, Ken Sweezey and Steve Kirsner, with Pavilion Management, requested a citizen's arrest of Lodge, Kuba, Bolbol and Cuviello. (DeMartini managed to slip free.) The four, after being cited, retreated outside the parking lot. The Police Department, citing the lawsuit. referred all questions to the city attorney's office. "We've been in the parking lot since the Animal Open House has been there," insists DeMartini. "We've come to sort of an understanding [with the Pavilion] over the years of what our First Amendment rights are. I assumed that it would be the same thing as in previous years, and I assumed when the police came they'd say we had a legal right to be here. Instead, they came and started arresting people. And so that was very unusual, very different." Elephant's Memory Common understandings of free speech law indicate that Pavilion security and San Jose police might have a point in their tangle with the animal rights activists--streets, parks and sidewalks are acceptable venues to protest, everything else is not--or so it seems. "Our constitutional presumption of classic speech forums are streets, parks and sidewalks," says David Green, a staff attorney for the Oakland-based First Amendment Project. "A parking lot is not something that has been historically opened for speech, but in a case where a parking lot is similar in purpose and assumption to parks, [there could be debate]. But [the animal-rights activists] were arrested for trespassing, which means they did not have the legal right to be there. Trespassing says an area is not open to the public. That's what's troubling; [HP Pavilion and the city] are not using a pre-made speech policy. That's clearly not what they're doing. They're charging people with a charge that is certainly a frivolous charge." Indeed, a closer look makes the issue far more debatable. First, the HP Pavilion was constructed with taxpayer money through the Redevelopment Agency. Of the $162.5 million cost of the building, $132.5 million came from public funds. The city of San Jose owns the arena. HP Pavilion Management, however, claims the property is private and open only to invitees, or ticket-purchasing guests. Second, though Pavilion Management's contract with the city allows for collaboration with the city for security, crowd control and parking concerns, there is no indication the city should be involved in speech-mitigation tactics with private managers. Both police reports and videotapes of the protests indicate that HP Pavilion, the police and the city attorney consulted prior to opening night to discuss how to handle demonstrators. It would be very difficult to argue, especially since recordings of the leafleting exist, that the activists posed any sort of security concern. Corroborating evidence from the video tape and police reports, Sweezey says that because of concerns about the protesters from the previous years, HP Pavilion representatives had met with both the Police Department and the city attorney's office, specifically Karl Mitchell, to discuss what they could do to address their property rights concerns. "We went through the thought process with him [Mitchell], looked at blueprints," Sweezey says. Assistant City Attorney Bill Hughes, however, is more guarded about the interaction with the Pavilion. "The city attorney office provides legal counsel to the city council and city staff, not to private management," says Hughes. "What he's [Sweezey] describing is coordinating activities that occur in the city. I certainly wouldn't describe the city attorney office as giving advice to Arena management people." Third, Lodge and the others were arrested under California's trespassing code, which allows for arrest if a person refuses to leave an area that is "lawfully occupied by another and not open to the general public," another difficult argument to make concerning the very public event of a circus. Furthermore, the code specifically indicates that it "shall not apply to persons on the premises who are engaging in activities protected by the California or United States Constitution." Trespassing was, in fact, the concern, affirms Sweezey, who heads up the Pavilion's guest service division. "They didn't have a ticket, they weren't invited to be on the private property, weren't respectful of the request to move on public sidewalks," he explains. "This applies to anyone who comes here. It was a trespassing issue, totally. Frankly their signs, most of their signs are text ... [so profanity wasn't an issue]. There were some really ugly pictures of dead animals that frankly I don't think are good for young kids to see, but that wasn't the reason. They were still holding the same signs on the sidewalk. That's not the issue--the issue was they were on private property and they did not leave when asked." However, in a telling scene that appears in the video footage from the evening of the arrests, Sweezey seemingly contradicts his explanation when asked by Bolbol why he isn't asking others milling in the parking lot for their tickets. "You should be asking everybody if you're not discriminating," objects Bolbol. "Well, they're not holding a sign," responds Sweezey. "There were a lot of issues," adds Deputy District Attorney David Tomkins, when asked why the charges were dismissed. "The fact that they were singled out--nobody else was being singled out; they were trying to exercise their First Amendment rights, which may or may not be an offense; and, the conduct itself was fairly minor--they weren't being violent. We looked at cost at prosecuting [and decided] it wasn't worth taxpayer money." Lastly, and perhaps most interestingly, the animal activists argue that by offering an Animal Open House, Ringling was in fact engaging in a form of public speech. In Ringling's promotional literature, the Open House is advertised as an opportunity for the public to evaluate firsthand how well cared for Ringling's animals are. Any form of public speech, the argument continues, should also allow for different perspectives to emerge. "I'm a mediator more than a lawyer," Lodge says. "I try to tell people to mediate and resolve the disputes in a peaceful manner. That's what I believe in, but in this case, I was angry, I felt violated. To be watching our rights dwindle and watching police and governments capitalize on sentiment going on today and think they can just herd people away angers me."

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the February 5-11, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.