![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

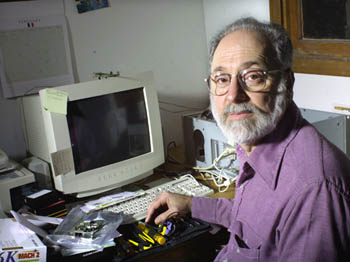

Photograph by George Sakkestad Ticked Off at Tech: Bill Lazar, who holds a Ph.D. in molecular biology, was seeking a career change when he enrolled at Silicon Valley College. Among the unprofessional conduct he witnessed there: A teacher threw a mouse pad in his face. Magna Cum Lousy Silicon Valley College targets people seeking a shortcut to a technology career. But $16,000 later, some of its best and brightest students say it didn't live up to its promises. By Justin Berton THE MORNING DRIVE PROGRAM on KYLD-FM thumps in 4/4 time when an ad for Silicon Valley College boom-booms its way through the speakers. A hyperactive turntable scratches away in the background as a ghetto dawg takes the mic: "Silicon Valley College is the place you want to be/Now the whole wide world is open to me." Before the spot ends comes a more serious, educated voiceover. "Don't get left behind," it preaches. "Don't settle for a minimum wage job." Richie Chavarria remembers hearing this ad on the radio. But it was too late--he'd already graduated from SVC. The 29-year-old bartender, father of a 3-year-old daughter, wanted one of those cashola high-tech jobs, one that got him home before his daughter was tucked into bed. Chavarria looked into SVC's popular Network Systems Administration program. After graduation, he was told by his "career counselor," he'd be ready to pass the big certification exams given by Cisco and Microsoft. He says he was told that 90 percent of the students pass. Pass the certs, the thinking goes, and watch out for the buckets of money falling on your head. So one morning last year Chavarria applied at SVC's San Jose campus, a cement and glass building in a business park located near Highway 85 and Bernal Road. He was accepted and was immediately approved for an $11,000 loan, scored $4,000 in grants and was back home by mid-afternoon. Yet just a few months into the deal, Chavarria heard the rumors on campus: SVC students were bombing their certification exams. And after Chavarria graduated last month with a solid 3.5 grade point average in hand, he bombed his certs too. "I didn't realize what was going on until a whole new module started," Chavarria now says, recalling the faces of youthful, hopeful minorities that stocked the classrooms after him. "It looked like they went to the basketball courts and told everyone to come on over and sign up for a loan. They were just pumping people through." Of Mice and Men BILL LAZAR FOUND Silicon Valley College on the Internet. A Ph.D. in molecular biology, he spent 15 years inside a research lab in Menlo Park before deciding he wanted to change careers--learn about computers, maybe even go into business for himself. He figured he'd pay the $16,000, attend SVC for a solid year and, just as the school's catalog advertises, become "prepared to pass the various industry standard certifications." In January last year, shortly after he began taking classes, Lazar started to notice that some of his teachers, younger techies who worked "in the field" by day, "lectured" by simply reading aloud from the tedious, dictionary-thick manuals. One teacher, he says, openly admitted he had never taught the course material before--and wasn't even certified to do so. "We'll just learn it together!" he joked. And one teacher, named John Powell, strangely threw things around his classroom. Erasers, keyboards, mouse pads. One afternoon in early August, Lazar took his seat in the front row of Powell's Network Technician class. Lazar often questioned Powell, who, several other students agreed, didn't take kindly to his most inquisitive student. "Oh, don't go there, Bill," Powell would snip. When Lazar did go there on this summer afternoon, Powell paused, picked up a mouse pad and, from just three feet away, hucked it in Lazar's face. Here sat Bill Lazar--Dr. Bill Lazar to some--eating mouse pad. He'd never attended a college like this before. Seven-Eleven YVETTE LAWSON well remembers the year of sacrifice she made to attend SVC. She would get up each morning, drop her two kids off at school in Morgan Hill and then drive to Campbell, where she worked full-time as a software instructor for the new hires at Alliance Title Company. At day's end, she would drive out to San Ignacio Avenue for her night classes at SVC. She would arrive home in Gilroy at nearly 11pm, long after the kids were in bed. "When I dropped my kids off at school," she recalls, "they would say, 'See ya tomorrow, Mom.' And it was 7 o'clock in the morning." But Lawson was determined to get her certs and break into the ranks as a network administrator--"There are just too many men in this field," she notes. She could then start making that "upwards of $120,000" her SVC career counselors told her about. She found the curriculum easy--and that wasn't a good thing. "I got all As in my classes," Lawson says. "All you had to do was memorize." Here, she picks random letter-answers to a multiple-choice test--"A, C, F, D. It was a joke. The teachers would read the test answers, then give you the test." If Lawson and her fellow students were surprised by the simplicity of the curriculum, they got a fast lesson on how quickly life changes outside SVC. Just before Lawson finished her eight-week course on Cisco's 6.0 routing system, she learned the Cisco exam she was working toward was being retired--in just two weeks--and being modified for the 7.0 version. She crammed for the test, muffed the first few questions and felt the plunge in her stomach. "When I learned I failed," Lawson says, "I started to question my knowledge--Do I have the brain capacity to hold this? I thought I'd go to the classes and have enough knowledge to pass these certifications, but I didn't. "With my grade point average,"--a more than respectable 3.85--Lawson says, "you'd think I would have skated through those exams."

The Looking Class: The Campus of Silicon Valley College, located on Ignacio Avenue, caters to students seeking their first high tech job. Gripe Fest MARK MILLEN, president of SVC's San Jose campus, is well aware of the gripes. As he points out, there are nearly 2,000 students who attend the three campuses, and, "In any business you have people that are unhappy. Right now, I've got students who don't like the design of the parking lot. I've got students who are upset with the vending machines." Millen is also clear about the mission of SVC. And he says it's not to guarantee students passage on the industry exams--he only wants to prepare them for "entry level" jobs. In contrast to the radio ads, which allude to a payday future, the SVC catalog describes its course work as merely an "introduction to client and server operating systems, hardware, and the networks that connect them." Then the description carefully but knowingly reads, "as a secondary objective students will be prepared for the following certifications: A+ Computer Technician, Cisco Certified Network Associate (CCNA), various Microsoft Certified Professional (MCP) exams, up to the Microsoft Certified Systems Engineer (MCSE) credential." Despite the fine print, several students complain that the certs are what's really being sold verbally by the school's advisers. Indeed, when an SVC adviser named "Chanbo" is reached by phone and asked if one should expect to pass the certs after a year at SVC, she swerves around hard promises but says, "We gear students for those exams, oh yes. But we can't guarantee you'll pass--no school can guarantee you'll pass them. But if you do well on the exams during the year, you should do well on those [certifications]. "It all depends on how studious you are." "Our priority is to help students get entry-level jobs," President Millen reiterates. "It's not our priority for them to pass those exams." He contradicts the 90 percent passage rate cited by Chavarria and others, saying, "We don't even know how many students pass those exams; we don't track it. We don't care." Given the Boot KAHLIN KURILIK, a Microsoft public relations employee, refers to tech schools like SVC as "boot camps" and says his company tells students to tuck in a few years worth of job experience before they even attempt taking the MCSE. "Just passing these exams doesn't really prepare anyone to operate in a real world environment," he says. Kurilik also says SVC currently isn't one of Microsoft's Authorized Academic Training Providers, which, if it were, would serve up the "official curriculum" of the world's largest software provider. And Microsoft isn't the only company that doesn't keep SVC on the screen. In August 1998, SVC taught the official Cisco Networking Academy. But in July last year, Millen says SVC voluntarily dropped Cisco. "They were asking to be more strict on the way we deliver content and we didn't want to conform to it." Yet Cisco reps recall the disconnection differently. Debbie Bruce, who oversees the relationship between Cisco and schools, says, "They were dropped from the Cisco Networking Academy. I got a note from the legal department. They said a student wrote a letter to us. Said they were unsatisfied [with SVC]. Now they're not part of the program." Letter of Discontent THE WEBSITE for Silicon Valley College seems made for students like Chavarria, Lazar and Lawson. On the home page there's a picture of a young African American wearing hospital scrubs, looking ... qualified. Next to him is a picture of age-spotted, wrinkled hands grasping the insides of a computer. And next to that is a photo of a young woman feeling comfortable surfing the net--all by herself. The message is that Silicon Valley College is such a good place, it can make minority guys doctor-smart, old people computer-friendly and young women independent and net-savvy. But for Chavarria, Lazar and Lawson, the SVC experience didn't end picture perfect. The trio of students were three of 31 (roughly one-third of the graduating class) who signed a letter protesting their "education" from SVC. The students' treatise, delivered to President Millen, called for classes to start on time, teachers to be educated before they taught the classes, and for the much-heralded job placement center to post better leads than receptionist gigs that pay $11 an hour. Today, Lazar is still at home in Sunnyvale, sending out résumés. He is one of the few students from his class that did pass the MSCE--no thanks to teacher John Powell, he adds. (Millen wouldn't comment on Powell, and the teacher didn't return phone messages from Metro.) Lazar says his experience in grad-school studying helped him plow through the vast material needed to pass the certs. Also, he spent weekends and late nights reading from texts he purchased on his own, not the suggested titles from SVC teachers. Yvette Lawson has given up trying to pass her exams. "Now I've got a $16,000 loan to pay off and I don't have shit in return." Richie Chavarria did land an entry-level job as a technician at a computer shop in Gilroy, doing minor repairs. He got the job through a guy he knew at his bar. SVC President Millen insists no matter how disgruntled a handful of students feel about their time at SVC, his school remains successful in finding jobs for students. In the 2000 graduating class, Millen claims, 89 students finished the year--and 81 were placed with a job by SVC. "We won't graduate anyone until they are ready and feel comfortable to go out there and work," Millen says. "Don't forget, they represent us." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the February 8-14, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2001 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.