![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

El Niño Behind Glass

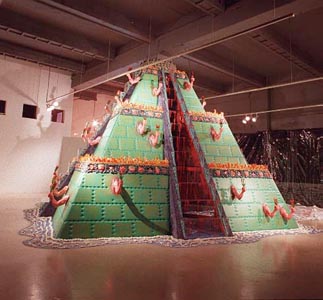

Christopher Gardner Fabulous de la Torre Boys: An 'Aztec-meets-low-rider pyramid' anchors 'El Niño's Wake,' the artists' latest multi-symboled installation at MACLA/San José Center for Latino Arts. The de la Torre brothers open a window onto the essential flux of being, in their new installation, 'El Niño's Wake' By Ann Elliott Sherman LEAVE IT TO the de la Torre brothers to wring new meaning from that media-saturated meteorological whipping boy, El Niño. Simultaneously the nickname of the havoc-wreaking cyclical shift in ocean currents and of the Christ child in México, "El Niño" is, as the artists put it, "the perfect modern demigod of ambiguity." Their current installation at MACLA/San José Center for Latino Arts explores the phenomenon of duality personified by this destructive savior. Processed through gray matter stimulated by high and low culture on both sides of the U.S./México border, Jamex and Einar de la Torre's unblinking examinations of cultural gray areas always yield an exuberant critique. El Niño's Wake is no exception--it's Mexican mythology and glass art deconstructed and reassembled with a glue gun. The reverberations of their vision rumble through as many layers as the viewer can sift; the symbols are both bilingual and thoroughly rooted in the transmutational Mexican immigrant experience. But what El Niño's Wake particularly demonstrates is how the de la Torres' hybridization of image, materials and tone encapsulates not only the border region's ethos but also the ancient Mesoamerican worldview of "the essential flux and interchangability of states of being." The initial focal point of El Niño's Wake is a huge Aztec-meets-low-rider pyramid surrounded by whitecapped "floodwaters." Brass upholstery tacks and swipes of chartreuse paint turn tuck-and-rolled aqua naugahyde into three-tiered walls of "blocks." The upper edge of each level of the pyramid is banded with tableros of pseudo pre-Columbian glyphs with a profane and kitschy twist. Plaster-cast headdressed faces grin goofily from smoke-blue "stela," some kind of extruded epoxy squeezed on like cake decoration to simulate carved stone. The heads alternate with spray-painted smashed beer cans and miniature black velvet bullfighting scenes. Along the top of each level, shards of clear broken bottles brushed with red and yellow paint do double duty as flames and the kind of security measure used to keep the riffraff out. Thirty-six muscular arms wielding broken bottles erupt from the pyramid's sides, like a force of nature that can't be denied. Running up the center of each side of the pyramid, steps of clear, paned glass drip with sacrificial "blood," their sides inscribed with the scroll motif found in the Quetzalcoatl pyramid in Teotihuacán. The steps are windows into the pyramid's interior, where ofrendas of empty beer bottles and blood-spurting, crucified glass hands "float" in a vinyl sea, eyed by the occasional glass shark. Facing the steps at each of the four directions is a ticky-tacky foil-and-Xmas-light shrine to Our Lady of Guadalupe, but the virgen has left the building, her empty cloak now protecting an electric "candle." A PILGRIMAGE around the pyramid brings the viewer face-to-face with El Niño himself. In the 1997 version of the installation, a caged El Niño was threatening to bust out, but now he's voyaging to the sun, leaving his dismembered counterparts behind for the sharks. What appeared to be the installation's beginning, the pyramid with its sacrifices, is actually the end of El Niño's Wake. Consider, Jamex and Einar suggest, the Aztec "Flowery Wars" to capture prisoners destined for sacrifice tantamount to campaigns against "illegals." Gotcha! El Niño winks. Since this is a realm of constantly shifting identity, the artists have given their Christian deity the same fair coloring traditionally ascribed to the human form of Quetzalcoatl. Furthermore, the vessel that carries El Niño is the braided rattlesnake skirt of Coatlicue, a mother goddess who underwent several cultural transformations to become Our Lady of Guadalupe. Here's some more symbolic reinvention, border-style: the angel traditionally shown beneath Guadalupe here takes the form of Alberto Coyote, star mediocampista of Guadalajara's Chivas soccer team. Not only is that the de la Torres' hometown team, but in a lovely bit of synchronicity, the team jersey he wears features the same red and white stripes worn by celestial messengers in Mixtec codices. The sun, El Niño's father, is represented by what the brothers call "an ultracontemporary version of the Aztec calendar," as much a wheel of fortune as a measure of time. In their trademark barrio baroque style, deploying strategically placed black fur, beads, "obsidian" arrows, bike reflectors and glass doodads, Jamex and Einar give equal time to past and present objects of worship: corn, crosses, women's legs, sperm count. The four squares traditionally representing the demise of previous suns or worlds have been replaced with stained-glass panels symbolizing other twists of fate or lost glories: braceleted hands wrapped around a gun or dagger, a vaquero's boot, a Nike cleat, all framed by an ongoing game of dominos. In the center, an awesomely crafted glass head of Tonatiuh, the fifth sun, stares out from the hub of a customized bike tire. The deliberate juxtaposition of this artistry with gilded plastic fasteners is vintage de la Torre ironic deflation. Even at the end of the millennium, the more everything changes, the more it stays the same. Part declaration of a state of emergency and part celebration of survival, El Niño's Wake is a party for the ages.

El Niño's Wake runs through March 13 at MACLA/San José Center for Latino Arts, 510 S. First St., San Jose (408/998-ARTE). [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the February 11-17, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.