![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

Buy 'Lou Harrison: Composing a World' by Leta Miller and Fredric Lieberman.

|

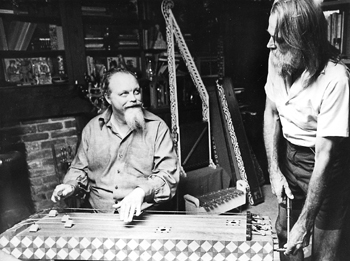

Goodnight, Daddy: Lou Harrison died last week at the age of 85. The Last Daddy A Metro music critic remembers his four decades with Lou Harrison By Scott MacClelland Lou Harrison never felt entirely comfortable being a composer, and often said so. John Cage, his friend, advised him to get over it. "You were elected," Cage told him. As if to underscore his ambivalence, Harrison would occasionally be surprised to find himself the author of music he had forgotten. Listing his creative activities--composer, performer, dancer, calligrapher, designer, poet, scholar--almost seems like an exercise in trivial pursuit. In truth, his ambivalence was over labels, not creativity. For his many expressive vectors, Harrison distilled an organizing credo, a motto for action: "Cherish, conserve, consider, create." And despite the multitude of his creative outlets, Harrison's more than 300 distinctively original works, expressed across a vast range of styles, mark him as one of the giants of 20th-century American music. Two things have always amazed me about Harrison: first, the protean range of his creativity, and second, the capacity of audiences to "get" him. I know of no classical or avant-garde musician in California who has not been affected by Lou's music, and that's not even considering the hundreds who knew him personally and whose judgment therefore is positively less than objective. No one who knew Lou took with them anything less than an indelible impression of his magnificent personality. I first met Lou Harrison in 1963. He and Richard Dee were touring a program of Chinese classical music, which they played on Chinese instruments, and were setting up for a performance at San Diego State, where I was a student. At that time I knew nothing of Lou, but was intrigued, like so many others, by what I saw and heard. I engaged him in conversation, and found him not only eager to expound, but extraordinarily generous with his time in doing so. My contact with him stepped up after I relocated to Monterey and began attending the Cabrillo Festival, and included many visits to his home for one-on-ones and social events. I recall asking Lou questions that were impertinent at the least, and maybe even silly, but he always gave them thoughtful answers. "What other composers would you choose to sound like?" I asked him. Without hesitation he declared, "Brahms and Hovhaness." I had never before imagined hearing those two names in the same breath. But, on reflection, it should have been obvious to me. Lou's energy seemed boundless. Even when health problems laid him low, he would always somehow come bouncing back. That death should come while he was on the road can be no surprise. He was doing what he loved: traveling to bask in the celebration of his music, to join in the exuberance of which he was the cause and the best example. Lou didn't have a mean bone in his body. If he couldn't say something nice about another composer's music, he couched it in positive and respectful terms. The naughtiest thing he ever wrote, while a critic in New York, was a description of Janacek's Sinfonietta for Orchestra as "New Jersey with peasants." The remark sounds more like Virgil Thomson, who was Lou's journalistic mentor at the time. Jeff Hudson, a journalist and music critic here in the '80s and early '90s, recalled Lou in an email a couple of days ago: "I remember his reaction when Virgil Thomson passed away. Lou looked at me and said, 'Jeff, the last of the Daddies is gone.'" Lou wouldn't have seen himself as one of the daddies. Among the likes of Ives, Cowell, Schoenberg, Copland, Cage and Thomson, Harrison saw himself as the new kid on the block. But in a real sense, Harrison leaves the greatest influence of them all. Why? Because he tore down forever the traditional musical barriers between Eastern Asia and Western Europe (including America) as surely as if he had single-handedly torn down the Berlin Wall. Harrison doesn't deserve all the credit, but his dogged determination to connect cultures--he often referred to Western classical music as the music of "northwest Asia"--finally brought musicians from both sides of the Pacific Ocean inescapably to the same page. Virgil Thomson compared Harrison to Mozart in his capacity to assimilate remote music and speak its language as fluently as his own. Among those two or three Western composers who imitated Javanese gamelan music, not a single one assimilated the culture and learned to speak it with his own voice as Lou Harrison did. In reflecting on the great man, Phil Collins, founder of Santa Cruz's venerable New Music Works, commented, "There are few composers of the 20th century whose music reveals so many dimensions of beauty as do the compositions of Lou Harrison. The radiant hues and far-reaching global vocabulary of Lou's orchestrations, together with the infectious rhythmic grooves and perfectly formed movements, are signature qualities of his work. Not to mention that exquisite melodic core, the real pay dirt of every work Lou composed." [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the February 13-19, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.