![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

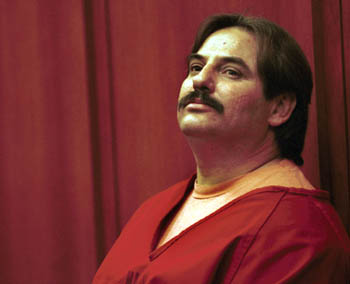

Photograph courtesy of Gerald Schwartzbach Big Buddy: In the early 1980s, shortly before entering prison, Glen William 'Buddy' Nickerson enjoys a domestic moment as he relaxes with his baby daughter. Almost 16 years later [inset], a slimmed-down Buddy as he appears in a mug shot from the state prison in Lancaster. Buddy And the System Buddy Nickerson has spent the past 16 years in jail for a pair of murders more and more people are saying he didn't commit. But don't call him an innocent man. By Will Harper BUDDY NICKERSON SPENT Christmas this year the same way he has for the past 16 years: locked inside a correctional facility for a crime he insists he didn't commit. Because of a holiday staffing shortage, guards at the state prison in Lancaster ordered a lockdown, leaving the 298-pound convict cocooned inside his 5-by-10-foot cell watching the 13-inch color television set his father had given him three months earlier. He ended up dozing off to the Jimmy Stewart classic It's a Wonderful Life. But unlike virtually every other prisoner in the place, Glen William Nickerson Jr. actually could dream that night: Soon, very soon, it truly could be a wonderful life. The term "wonderful" would have to be used loosely in this case, of course. Nickerson, now 45 years old, has spent more than a third of his life in custody for the Sept. 15, 1984, murders of San Jose crank dealer John Evans and Evans' half-brother, plus the attempted murder of their friend. During the years of his incarceration, his mother passed away, his youngest brother, Nicky, died from what family members believe was a self-inflicted gunshot wound, and his daughter and son have grown into adults without him around. Adding to Nickerson's sense of injustice is the fact that no physical evidence has ever been found linking him to the crime he was convicted of. The prosecution's star witness was a brain-damaged victim of the gang-style suburban shootout who admitted he never saw any of the faces of his assailants because they all wore ski masks. The two sheriff's investigators who put Nickerson away were later found by a judge to have lied under oath during a trial of a co-defendant, whose case cost taxpayers an estimated $3 million and stands as one of the most drawn-out and embarrassing trials in local law enforcement history. Buddy--still called by a childhood nickname that would come back to haunt him during his trial--did manage to escape getting the death penalty. But prison life over the past decade and a half has nearly killed him anyway. He almost died during surgery when doctors tried to repair a hernia and wound up discovering severe intestinal blockage. Various other ailments have trimmed him down from 425 pounds at the time of his arrest to 298 pounds today. "Don't worry," he joked to one of his lawyers during another one of his health scares, "the only way I'll die here is if they let me out-- I'll probably have a heart attack." Sometimes it seems the only thing keeping him alive is his stubborn insistence on proving his innocence and the help of a couple of liberal lawyers who think he got a raw deal. That stubbornness may finally be paying off. There's new evidence that has turned up: a DNA test on the mysterious trail of blood leading from the crime scene has now been identified as belonging to another man, who police arrested a year ago. A federal judge is seriously mulling over whether to let Buddy Nickerson out of prison. And local law enforcement is being confronted with the disturbing possibility that a flawed investigation cost an innocent man 16 years of his life. Doll Parts THE STORY OF Buddy Nickerson starts on St. Patrick's Day of 1955, when he was born the oldest son of Glen Sr. and his wife, Doris Jean. Buddy had an older sister, Glenna, a younger brother named Richard and another younger brother, Harry, whom everyone called Nicky. Unlike his thin, lanky siblings, Buddy was always chubby. Photos of him from high school show a handsome, baby-faced adolescent. Glen Nickerson Sr. now says he can't remember why everyone started calling his oldest son "Buddy." But Buddy himself remembers it well: In the late '50s or early '60s, a popular doll hit the market, sort of like a Raggedy Andy. It was called "Buddy," a chubby boy doll who wore overalls and a smile. Family members saw a similarity between the Buddy doll and their friendly Glen Jr., and the name stuck. Buddy and his siblings grew up in an affordable tract neighborhood near Leigh High School, where Buddy dropped out in the 10th grade. Buddy's parents divorced in 1975, when he was 20, and Glen Sr., who now lives in Foster City, refuses to discuss practically anything about those years. "They were a real notorious family," recalls Richard Boone, a retired San Jose cop who used to patrol Nickerson's neighborhood. Their front yard looked like no one ever bothered to mow it, Boone chuckles. Neighbors would call police at least once a week to complain about the fighting at the Nickersons' house. "We were always going out there on 415s, which was [the code for] a family disturbance," Boone says. "They were always fighting--the mother, the father and the children. ... They were a typical 415 family, just hollering and pushing and getting into each other's way." Boone says the domestic disputes didn't result in blows being thrown, though occasionally household objects did get tossed. As for Buddy's late mother, Doris, her 1993 death certificate says she spent her life as a homemaker. A source who spoke with her on dozens of occasions describes her as a woman who smoked regularly, cussed like a truck driver and always believed her boys when they said, "Mom, I didn't do it." The Nickerson boys were well known to police. Young Nicky was a suspect in a half-dozen armed robberies and stabbed a bar bouncer in 1981. Middle child Richard got busted for possession of PCP and carrying a concealed shotgun in his trench coat. And Buddy. Well, Buddy liked to steal cars, with a seeming fondness for ripping off '60s Volkswagens. Sometimes he sold drugs. A survivor of San Jose's Cambrian Park neighborhood who remembers the Nickerson family well recalls Buddy as "a puke." "I remember Buddy being a big, fat slob who was always getting into trouble," says Boone. "Buddy was the biggest pain in the ass there ever was." By his late-20s, Buddy had a son and a daughter with two different mothers. The Santa Cruz County District Attorney tagged him in 1983 for not making child support payments. Paying the bills is hard when you don't have a regular job. Sometimes bar owners hired the walrus-sized Buddy to be a bouncer. Other times, Buddy did odd jobs around the neighborhood like removing a tree stump from John Evans' front lawn. But mostly, Buddy liked to get loaded. On the day of the Ronda Drive murders, Buddy says he spent the afternoon and evening drinking with his friend Keith Banks. That night, Dion and Kristin Banks--Keith's brother and sister-in-law--were throwing a party and Buddy served as bouncer. But Buddy ingested a few too many substances and started feeling sick. According to witness accounts, Buddy took off his boots in the house, went outside and fell asleep inside his pickup truck with his bare feet hanging out the window. Alibi witnesses later testified that they had seen Buddy fast asleep in his truck at the time when the murders were going down in another part of town. They remembered because they couldn't forget how badly Buddy's feet stank, recalls Nickerson's former public defender, Thomas Dettmer. Nickerson also claims that well before the murders he had resolved his beef with John Evans. A bartender corroborated Nickerson's claim, testifying that he saw Evans and Nickerson drinking beers together for 30 to 40 minutes without arguing, just a week or so before the shooting. Dettmer, now retired from the public defender's office, says he knew all during his trial that Buddy Nickerson was an innocent man. Dettmer blames Nickerson's conviction on the two lead sheriff's investigators, Brian Beck and Jerry Hall, who he says falsely fingered Buddy from the start. "They're a couple of cowboys," Dettmer says of Beck and Hall, "and they shouldn't be allowed to carry guns around."

Family Circle: Buddy (far left), shown here in a 1982 family photo with younger brother Nicky and mother Doris. Dead Man Pacing FOR YEARS Buddy and John Evans had run in the same circles, living in the same quasineglected suburban swath that surrounded the still-unbuilt Highway 85 corridor. Evans lived in an unincorporated section of Cambrian Park in an Eichler-style, single story wood-stucco home on Ronda Drive. At the time, Cambrian was accessible only by a maze of city streets, giving it a sense of remoteness. Sometimes it seemed as if Cambrian-ites lived in their own strange land far away from the burgeoning high-tech capital of the world. Evans' household included three pit bulls, Gigolo, Duchess and Dallas. Evans' neighbor testified that she owned wolves. In the early '80s, troublemakers like John Evans and the Nickerson brothers occupied themselves by peddling (and using) the lower class's new drug of choice, methamphetamine. The Nickerson brothers, who grew up just a mile away from Ronda Drive, often bumped into Evans at Otto's Garden Room, a well-known Hell's Angels hangout located in a no man's land on the outskirts of Los Gatos near an orchard and Highway 17. But by the summer of 1984, Nicky Nickerson and John Evans were on bad terms. As the story goes, Nicky, an 8th-grade dropout with a mean temper, barged into Evans' house with a sawed-off shotgun, looking to rob the crank dealer, who was known to keep up to $10,000 in cash around his pad. Evans' live-in girlfriend and the mother of his baby, Barbara Payne, had tried to slam the front door shut on Nickerson, but Nicky used his shotgun to block it. "Not so fast," he told her. He wanted to "talk" to John. Evans, meanwhile, was in the back of the house in his "office," where he regularly did lines on a hand mirror and admired his nude pinups. Nicky put Evans' girlfriend in a headlock, held the shotgun to her head and started walking slowly down the hallway toward the office. She later testified that as they made their way down the hallway, she pushed Nicky's shotgun upward and it discharged into the ceiling. Evans then burst out of his office and capped Nicky Nickerson in the chest, causing him to let go of his shotgun and fall to the floor. As the 22-year-old Nickerson lay wounded with blood seeping through his Pendelton--Payne later testified he looked like a Cholo with his hiked-up khakis and slicked-back hair--Evans literally kicked him out the door. Nicky survived, but the incident left him paralyzed from the waist down. He died nearly a decade later in an apparent suicide. After the shooting and word got around about what had happened, Buddy allegedly told sheriff's deputies, "I will give you people 30 days to take care of it or else I will." After that, deputies waited for the retaliatory strike. The Nickersons, however, weren't Evans' only potential enemies. Cambrian couch-surfer Murray Lodge, a drug peddler with a long history of violent crimes, also had a grudge against him. Lodge, who briefly lived with Evans for a time, told people that Evans once had held a gun to his head and threatened to kill him if he didn't pay the $1,200 he owed from past drug debts. Lodge also believed Evans had put a contract out on him. Dirty Dealing ON THE NIGHT OF HIS DEATH, John Evans acted like a man who expected something bad to happen. His mother and sister, who stopped by his San Jose home on Sept. 14, 1984, sensed he was agitated and nervous. When his sister first arrived, Evans' bodyguard, Mike Riley, welcomed her by pointing a gun at her head. Riley put the gun away only after Evans explained who she was. Evans had good reason to be edgy, and it wasn't just because of all the crank and cocaine he'd done that night. People wanted John Evans dead. At around 10pm on Sept. 14, 1984, Evans asked his mother and sister to leave his house because he had some "business" to do. Ten to 15 minutes after his mom and sister took off, the 26-year-old Evans jumped in his black Trans Am, which had five nude Charlie's Angels lookalikes painted on the hood, and left to do his "business." Riley took off in his Dodge Roadrunner. They left behind Evans' older half-brother, Mickie King, who lived in what used to be the garage, and Evans' boyhood pal Michael Osorio, who had come down from Sacramento earlier in the day. Osorio had known Evans since he was 11 and taught Evans how to manufacture methamphetamine. According to one court account, Osorio fell asleep in the front room looking at a pornographic magazine and awoke to the sound of the kitchen door being kicked in. Before Osorio could react, someone wearing a ski mask clubbed him over the head with a pistol. In his haze, Osorio could hear the pit bulls barking frantically in the old garage space. He thought he heard Evans' brother King promising someone he would call off the dogs if they didn't shoot. The masked assailants then handcuffed both Osorio and King with their hands behind their backs face down. One of the masked men asked Osorio about Evans' whereabouts. Osorio thought the voice belonged to Murray Lodge, a local who had stayed at Evans' house before. Osorio lied and said Evans had gone away for the weekend. The intruders didn't buy it and hit Osorio with a stick. Osorio would also later testify he heard the handcuffed King asking one of the assailants, "Come over here, Buddy, and loosen the fucking cuffs." The phrase "Buddy" would later become a matter of great debate between defense and prosecution, with the defense arguing that "Buddy" could have easily been a slang reference along the lines of saying, "Hey, pal, come over here and loosen the fucking cuffs." At around 1am, John Evans returned to his Ronda Drive bungalow. Neighbors later remembered hearing him arrive because, as usual, Evans was blasting his car stereo. "He's here," Osorio heard one of the men inside the house whisper. As he approached the front door, Evans sensed something amiss. He drew his .380 Beretta and slowly fit his key into the door. As the door swung open, all hell broke loose (investigators later found the key still in the door lock). As the prosecution's theory went, Evans grappled with one of the intruders and fired his gun repeatedly. Then one of the other gunmen came up and shot Evans in his left shoulder. Police later found bullet lodgings from Evans' gun in the porch ceiling, suggesting he continued firing his Beretta while falling backward after getting shot. The gunman then stood above Evans, who held up his right arm to protect his face, and shot him in the left temple at point-blank range. King and Osorio were both shot execution-style in the back of the head. Then everyone scattered. A brownish van slowly crept down Ronda and, one witness recalled, tooted its horn in front of Evans' house. Another witness heard a van door closing as if someone had jumped in. But not everyone got in the van on Ronda. Other witnesses saw two men running up Ronda onto Union. But none of the neighbors reported seeing an obese, 400-pound man fleeing the scene, defense attorneys say. A trail of blood ran from Evans' porch to the driveway, going west on Ronda Drive, turning left on Union and trickling over to the Lakeside Apartments on Heimgartner. One of the perpatrators had been shot by Evans. The blood trail would remain one of the nagging mysteries of the case--a mystery that investigators wouldn't solve until 15 years later. Authorities could never figure out to whom the blood belonged. It didn't match the blood type of anyone arrested for the murders in the months right after the crime, including Buddy Nickerson's. Cloudy Forecast SGT. BRIAN BECK arrived at Ronda Drive at 2:05am, about an hour after the shootings. He noted in his report that it was a warm summer night "with the temperatures in the upper 60s and light high clouds." A month earlier, Beck, a 14-year law enforcement veteran, had forecast the macabre scene now lying before him. He knew that in August, Evans had shot neighborhood thug Nicky Nickerson and that Nicky's fat brother, Buddy, might seek revenge. He told a patrol unit to make contact with Doris Nickerson to see if they could find Buddy at his mother's apartment on Cadillac Drive. "I felt there was a possibility of a retaliation shooting," Beck wrote in his Sept. 16, 1984, report. The two deputies dispatched to the apartment knocked on Doris Nickerson's door and she sleepily answered. Doris claimed she didn't know where Buddy was because he had skipped town. The Los Gatos Police Department wanted him for "embezzlement or theft," she said. The deputies suspected Doris Nickerson might be covering for her son. They later contacted Los Gatos police, who said they "had no [warrants] out for Buddy on anything." Meanwhile, Beck's partner, Sgt. Jerry Hall, was heading to Valley Medical Center to talk to victim Michael Osorio, who was still alive. Osorio had somehow survived a gunshot to the back of the head and responding officers found him crawling on his belly in a pool of blood inside Evans' house. Osorio might still be alive, but he was far from lucid. He woozily told the first cop on the scene that he had been asleep and didn't know who hurt him. But in the ambulance he told another deputy he saw two masked men. He also described the perpetrators as being of "average build," defense attorneys say. By the time he spoke to Hall, Osorio claimed to having seen "several people wearing ski masks." In obvious pain, Osorio told Hall he didn't want to talk anymore. Hall left without Osorio having identified any of the intruders. Soon after, though, Beck and Hall returned to the VMC intensive care unit to visit a heavily sedated Osorio, who had just undergone brain surgery. Beck and Hall reported that during the visit Osorio had recalled seeing four masked intruders and identified one of them as Buddy Nickerson. Osorio had seen Nickerson before at Evans' house when Buddy was doing some yard work. "I could never forget that fat motherfucker," Osorio would allegedly say later.

Jerry's Kid: Criminal attorney Gerald Schwartzbach, one of Nickerson's lawyers who has taken his case pro bono, has built a reputation for successfully employing unorthodox methods. Night Vision FOUR DAYS AFTER THE CRIME, Beck and Hall went to talk to 18-year-old Lakeside Apartment resident Brian Tripp. Tripp confirmed that he had seen a strange man with jeans and untied black boots wandering through the apartment complex around 1am a few days earlier. The teenager was coming back home from hanging out with his friends and went to check on his truck in the carport. Then Tripp saw someone standing 15 feet away, hunched over, with a towel or jacket held to his stomach. Nickerson's attorneys argued that the man was covering a gunshot wound. "Where the fuck am I?" Tripp recalled the stranger asking himself as he did a 360-degree turn. Tripp told the man to get out of the area if he didn't belong there, and the stranger ran away. Tripp described the man he saw as "a male Caucasian, 5 feet 11 inches-6 feet, 190-200 pounds, brown shoulder-length hair that was straight and dirty." Tripp told Beck and Hall that he "got a fairly good look" at the guy and thought he could identify him if he saw him again. Days later, Beck and Hall met with Tripp again, bringing photos of possible suspects to show him. After looking the photos over the first time, Tripp said he didn't recognize anyone. The second time the detectives showed him a photo lineup, Tripp got the sense they didn't like his answers from the first go-round. Beck and Hall, Tripp would recall years later, asked him things like "Are you sure he wasn't heavyset?" and "Are you sure his face wasn't pudgier?" Tripp started to hedge. He began doubting his initial recollection of the man he saw, he later testified. But it was not until Nickerson's trial that Tripp picked out the "right" guy. At the time of the crime Nickerson weighed more than 400 pounds. By early October, Beck and Hall felt they had enough circumstantial evidence to bust Nickerson--he had a motive, and a witness who had now placed him at the crime scene. On Oct. 3, 1984, deputies arrested Nickerson, charging him with two counts of murder with special circumstances and one count of attempted murder. Prosecutors planned to seek the death penalty. Conspiring Enemies WITH THE DEATH PENALTY hanging over his head, Buddy turned down what seemed like a pretty good deal: A 12-year prison sentence in exchange for a guilty plea. Nickerson reasoned that the offer was a good deal for a guilty man, but not an innocent one. "I wasn't going to plead guilty to something I didn't do," Nickerson says. Eventually, police arrested and charged three other Otto's regulars in connection with the crime: 27-year-old Murray John Lodge, 44-year-old Dennis Leroy Hamilton and 27-year-old Brett "Wolf" Wofford. The first day Lodge and Nickerson--sworn enemies, lawyers say--appeared in court together, the much smaller Lodge attacked and punched the bearded behemoth. A bailiff intervened, clocking Lodge over the head with his club, forcing blood to rush into Lodge's eyeballs. Then, during jury selection in 1986, the judge dismissed one jury panel when a prospective juror from Palo Alto recognized Nickerson as the guy who had stolen his car years before. But the defendants weren't the only ones creating a circus-like atmosphere. The star witness, Michael Osorio, admitted to fooling around in a motel room with another witness. Then there were whispers that Lodge's attractive young female co-counsel had a crush on her client. But perhaps most disturbing were the methods of sheriff's investigators Hall and Beck (the latter had been promoted to lieutenant by this time). Defense lawyers kept bumping into potential witnesses who said they had been interviewed by the two detectives, but there were no corresponding police reports or tapes of those interviews. Beck and Hall finally handed over a shoebox full of cassette tapes and hundred of pages of notes two months into jury selection. As it turns out, the two cops had a habit of taping interviews then tossing them into a shoebox to be recycled if they didn't think the interview produced anything useful. On one of the tapes in the shoebox Beck boasts about making defense lawyers' jobs as difficult as possible. "We don't lie to the defense lawyers, [but] they have to really pry to find out what we know." Judge Foley ruled that the investigators had withheld evidence, Nickerson's attorneys say, and declared a mistrial in the summer of 1986. Limited Appeal AS IT TURNED OUT, the mistrial simply delayed the inevitable for Buddy Nickerson. A year later, a jury convicted Nickerson of first-degree murder and attempted murder based primarily on the witness testimony of Osorio and Tripp. The court sentenced him to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Co-defendant Dennis Hamilton, whose ex-wife's gun was found at the crime scene, was sentenced to 65 years to life. Brett Wofford, whom prosecutors decided wasn't at Evans' house the night of the murders, pleaded to an accessory charge for supplying the handcuffs. By the end of 1989, Nickerson had exhausted his state appeals and appeared doomed to spend the rest of his life behind bars. But Nickerson did have two unlikely allies in Ed Sousa and Gerald Schwartzbach, the attorneys for Buddy's enemy, Murray Lodge. After the 1986 mistrial, the court severed Lodge's case from the other defendants. By then, prosecutors came to believe that Lodge had been the ringleader and, most likely, the triggerman. They decided to seek the death penalty only for Lodge. Ed Sousa became a lawyer in 1986. The young San Jose attorney would spend seven of his first eight years as a lawyer representing Lodge. Schwartzbach, an experienced criminal lawyer, joined Sousa as his co-counsel in 1989. Sousa was the more detail-oriented of the two, amassing more than 36 banker's boxes of notes during the Lodge trial. Schwartzbach was the strategist, having earned a reputation in his 19 years as a criminal attorney for devising unorthodox defenses that somehow worked. He was one of the first attorneys to use the battered-women's syndrome defense. As the Lodge case slowly moved forward, Sousa and Schwartzbach became more and more convinced of Nickerson's innocence. And they became increasingly critical of Brian Beck and Jerry Hall. When they questioned witness Brian Tripp on the stand, Tripp recanted his identification of Nickerson during the Lodge trial. If Nickerson weighed 400 pounds at the time of the crime, Tripp testified, he couldn't have been the man he saw that night. According to Sousa and Schwartzbach, Tripp conceded Beck and Hall might have influenced his previous identification. Michael Osorio continued to identify Nickerson as one of the assailants, but the two defense lawyers grew suspicious of the circumstances around the first time he named Nickerson. He was alone in the intensive care unit with Beck and Hall. Schwartzbach began theorizing that the two cops had effectively planted the idea in Osorio's mind while he was in a highly suggestible state. But that was only a theory. The defense attorneys hadn't yet uncovered any willful effort to distort the facts. Sure, Beck and Hall could be rightly accused of questionable and clumsy record keeping, but not anything as serious as lying. And then, eight months into the Lodge trial, the two lawyers came across something that would cast a sinister shadow over the two investigators who had put Buddy Nickerson away. Spontaneous Combustion ON JAN. 21, 1985, Beck and Hall drove to the Nevada state prison in Carson City to pick up Murray Lodge and return him to Santa Clara County in connection with the murders of Evans and King. In the months after the Ronda Drive shootings, Lodge had turned up in Winnemucca, a rural town in northern Nevada with a population under 8,000. He and a friend held up a gas station there and later were convicted of armed robbery. The ride home lasted four hours. During the trip, Beck and Hall later claimed, Lodge started making unsolicited, "spontaneous" statements. From a legal standpoint, the word "spontaneous" was crucial because the officers hadn't read Lodge his Miranda rights. When they returned, Beck filed a police report saying that Lodge had acknowledged breaking into the Los Gatos home of a retired school teacher the evening after Evans was killed. "Other than the above statements," Beck wrote in a follow-up report, "the entire trip was spent discussing the weather, the scenery, the quality of jail food, prison atmosphere and women." In the following years, Beck and Hall repeatedly denied under oath having tape-recorded the conversation. They also swore they didn't try to bait Lodge into saying something stupid by dangling a lighter sentence in front of him in exchange for his cooperation. Eight years after that four-hour drive from Carson City, Sousa and Schwartzbach went to talk to Buddy Nickerson's former public defender, Tom Dettmer. It didn't take long for the subject of Beck and Hall and the Carson City trip to come up. Contrary to Beck and Hall's claims on the stand, Dettmer knew the detectives had tape-recorded part of their discussion with Lodge. In fact, he had heard the tape, Dettmer told Schwartzbach and Sousa. Sousa immediately went to his office to retrieve the shoebox full of cassettes Beck and Hall belatedly turned over in 1986. Dettmer went through the stack of tapes and popped one in his cassette player. The interview with Lodge, he vaguely recalled, was on the back of a taped interview with another witness and started randomly somewhere in the middle of the tape. Dettmer cued the tape and pressed play. After a few minutes of silence the attorneys heard the voices of Jerry Hall, Brian Beck and Murray Lodge. "So," a transcript of the tape shows Hall asked Lodge, "have you given your situation back in San Jose much thought?" "Like what?" Lodge replied. "About the case against you," Hall said. "As far as what?" Lodge said. "As far as your being cooperative," Hall explained. The tape then made a clicking noise, as if being stopped and started again. "I think in my case," Lodge said cautiously, "I really ought to wait 'til the preliminary [hearing], see what they got on me, don't you really think?" "Well, that certainly, you know, wouldn't hurt you," Hall fumbled, looking for another opening. "The information we have against you, I think, is pretty substantial," Hall pressed. "But like we'd mentioned before, in your giving consideration to providing us information, you know, and whether they would consider dropping the special circumstances or what they might consider doing for that." But Lodge, a seasoned criminal, didn't take the bait. From there, Lodge asked about the last time someone died under the death penalty in California and whether Death Row inmates get conjugal visits. His only slip-up was admitting to kicking in the Los Gatos teacher's door and breaking into her house.

This Bud's for You: Bay area defense attorney Ed Sousa is convinced that authorities have made a mistake in fingering Buddy Nickerson for the 1984 murders of Evans and King. Taped Conviction SCHWARTZBACH and Sousa had what they wanted: Beck and Hall clearly were trying to persuade Lodge to blab by suggesting they could help him avoid the death penalty. The two attorneys then played the tape for Superior Court Judge Robert Foley. On the morning of Feb. 8, 1993, Foley theorized in open court why Beck and Hall did what they did. "Why was a tape preserved?" Foley asked rhetorically. "It wasn't meant to be preserved. They extracted the one statement they deemed relevant, but since they didn't have a smoking gun statement, they consigned the tape to the recycling box, supposedly never to see the light of day again. "What effect does this have overall? [It] certainly puts in question in my mind all the testimony of Sergeant Hall and Lieutenant Beck." For their part, Beck said he didn't know the discussion was being recorded; Hall blamed a faulty memory, saying he simply forgot that he had taped parts of the conversation with Lodge. Later that afternoon, Foley called the jury into his chambers. "It is my belief that the officers willfully perjured themselves in your presence." Foley then declared a mistrial and told the jury they could go home. Despite the setback, 18 months later prosecutors convicted 37-year-old Murray Lodge of double homicide and attempted murder. In a desperate attempt to save their client's life, Schwartzbach insisted Lodge, known to have a good singing voice, perform for the jury the Elvis classics "Blue Suede Shoes" and "Love Me Tender." He wound up avoiding the death penalty. After the Lodge trial was finally done, both Sousa and Schwartzbach knew they had unfinished business. The two lawyers told Buddy they would do whatever they could to get him out of prison. And they would do it free of charge. They just didn't know exactly how to do it yet. Unsolved Mystery RAY MEDVED, a former detective sergeant for the Santa Clara Police Department, exclusively investigates unsolved homicide cases for Santa Clara County District Attorney George Kennedy. One of the ancient cases on Medved's desk in the winter of 1998: the 1984 murders of John Evans and Mickie King and the attempted murder of their friend Michael Osorio. Prosecutors had thus far convicted three men of the murders as well as another for supplying the handcuffs (but who didn't participate directly in the shootings). But a couple of unsolved mysteries in the case remained, such as the trail of blood that started in Evans' driveway and stopped at the nearby Lakeside condominiums. The blood did not match the blood types of any of the suspects police arrested. Prosecutors theorized that the blood must have belonged to a fourth suspect shot by Evans during the initial scuffle. Some people around the DA's office began calling the mystery suspect "Bullet Bob." The day before the murders, suspect Dennis Hamilton brought over a man to his ex-wife's house whom he identified only as "Bob." Norma Goytia, Hamilton's ex, described "Bob" to investigators as being his late 20s, good looking, about 6 feet tall with curly, blondish-brown hair. Fourteen years after the murders, Medved got some information that led him to a "Bill," but not a "Bob." He asked the county crime lab to do a DNA comparison of the blood found near Evans' home to that of a prison inmate in Susanville named William Carl Jahn. Jahn was doing time in an unrelated case for illegal possession of meth and a .22 caliber Ruger. When Medved got back the lab results, they showed that the blood sample taken from the Ronda Drive crime scene more than a decade earlier matched Jahn's blood. The serologist told Medved that the DNA characteristics found in the samples occur in one in a million Caucasians. Medved later went to talk to Jahn and asked him to lift up his shirt. Medved wanted to see if he had any bullet wound scars. On the left side of Jahn's torso Medved saw a straight, half-inch scar. Jahn said it was a stab wound and insisted that he had never been shot before. Medved didn't have the medical expertise to prove otherwise, so he later obtained a search warrant to have doctors examine Jahn's scars. According to Medved's court affidavit, the X-rays "revealed material consistent with metal fragments in his left thigh and in the area of his right shoulder. The examination of the exterior of [Jahn] revealed a scar on his left thigh that is consistent with a bullet entry wound and a second scar that is consistent with a bullet exit wound." Medved wasn't the only one interested in Bill Jahn. By the fall of 1999, Schwartzbach and Sousa had caught wind of the district attorney's investigation of him. They decided to pay Jahn a visit at Susanville. After 15 years of carrying around a terrible secret, Bill Jahn started to spill his guts to Schwartzbach and Sousa. Jahn admitted he was surprised "this" hadn't come up long ago, according to the sworn declaration Schwartzbach filed in San Francisco federal court after the visit. Jahn admitted seeing Evans shot and killed, but insisted he himself didn't kill anyone. He also told the attorneys that he never met Buddy, though he had heard about the Nickersons. And he said Buddy Nickerson was innocent. Strange Days TO PUT IT MILDLY, 1984 was a crazy year for Bill Jahn. On Feb. 17, a judge sentenced him to five months in jail for possession of cocaine and a hypodermic needle. Three months later, jail administrators let Jahn walk after getting the standard one-third time off his sentence for time served. Unbeknownst to them, Jahn was supposed to start serving another 180-day sentence on May 17 for a separate charge of carrying a concealed gun. In retrospect, he may have wished he was still in jail during that time, seeing as how he wound up being shot the night of the murders. Jahn managed to stay out of trouble until four days before Christmas of 1985, when police nabbed him for driving with a suspended license and petty theft. The cops quickly discovered that there was a bench warrant out for his arrest for not serving his jail time on the earlier weapons charge. Jahn served 17 days in jail before making bail. In May 1986, Judge John McInerney granted Jahn three years probation. According to a court declaration filed by Kimberlee Jahn, her husband ditched her and their 1-year-old daughter in October 1987. She said Bill Jahn took the only car the family owned and "left the trailer for good." After that, his ex-wife claimed, Jahn's child support checks would bounce because "he is again using money to purchase drugs so that he can continue to get high day to day." She also accused her former husband of being prone to rage "since he has been involved in violence in the past of taking out his violent actions against me and our daughter." Kimberlee added that Jahn "has always threatened me that he would bury me in our backyard." By the mid '90s, Jahn had gotten married for a third time, fathered a second daughter, and started a car repair business in Campbell called Central Bodyworks. In March 1996, Campbell police received a report from five unnerved Central Bodyworks customers who had complained to Jahn about the shoddy work he did on their cars. According to the report, Jahn retreated to his green Ford Bronco, reached into his glove compartment, pulled a semiautomatic pistol and yelled at the unhappy customers, "I'm going to kill all you motherfuckers. Do you want to pay for your cars or not?" When police searched the shop they did not find a gun, but did come across a full box of 380mm ammo and a gun holster. The cops ultimately charged him with possession of marijuana, gun ammunition and fireworks. The following year, San Jose cops started casing Central Bodyworks, which is now under new ownership. On Dec. 11, 1997, San Jose police executed a warrant and found 10 ounces of meth, $3,798 in cash and a .22 caliber gun in a toolbox that Jahn claimed belonged to someone else. Although San Jose police arrested him at the time, it took almost a year for prosecutors to actually file charges against Jahn. Jahn told Schwartzbach and Sousa that authorities were trying to squeeze information from him about the Hell's Angels. But Jahn claimed he didn't reveal anything because he didn't know anything about the biker club. Around the time authorities charged him in December 1998, they seemed less interested in what Jahn knew about the Hell's Angels. Now they were beginning to ask him about his relationship with Murray Lodge and took a sample of blood. His 15 years on the lam were finally about to come to an end. In March 2000, prosecutors charged Jahn with two counts of murder connection with the 1984 shootings of Evans and King.

Exit Wound: After leaving a trail of blood from the 1984 Ronda Drive murder scene, William Carl Jahn managed to avoid suspicion regarding the crime for more than 14 years. A Final Chance THE ARREST OF William Jahn gave Buddy Nickerson new life in the legal system. U.S. District Court Judge Marilyn Hall Patel had initially dismissed Nickerson's last-ditch appeal because it was filed five days after the statute of limitations ran out. But Schwartzbach persisted and Patel reconsidered her earlier dismissal after reviewing the evidence in the Jahn case. In a Sept. 14, 2000, memorandum, Patel declared that Nickerson had made a persuasive case for "actual innocence." "[T]here is no testimony," Patel said in her memorandum, "that any other perpetrator other than the bleeding perpetrator ran to or through [Lakeside Apartments]. ... If this man was really Jahn and not Nickerson, Nickerson's new evidence does constitute exculpatory evidence." In light of the new evidence presented by Jahn's arrest, Patel concluded, "The court finds it difficult to maintain its confidence in the outcome of Nickerson's trial." But the state attorney general's office, which is representing the Santa Clara County district attorney in the appeals case, insists that Patel simply doesn't have all the facts before her yet. At this point, argues Deputy Attorney General Gregory Ott, Patel has relied heavily on the selective reading of the case made by Nickerson's lawyers. Ott is currently working on a brief presenting Patel the facts as the prosecution sees them. As for the newest suspect in the case, William Jahn has pleaded not guilty. He is scheduled to have a preliminary hearing in the spring. In Jahn's defense, his attorney, Harry Robertson, asks how Jahn could have avoided detection all these years in a case filled with blabbermouths. "After 16 years," Robertson reasons, "if [Jahn] had been involved in the original conspiracy it would have come out a long time ago." Judge Patel is expected to rule on a motion to release Nickerson on his own recognizance within the next 45 days. Even if Patel rules in his favor, Nickerson's legal journey is far from over. The most Patel can do, sources say, is order a new trial for Nickerson. Assistant District Attorney Dave Davies predicts that his office would almost definitely retry Nickerson should Patel rule in Nickerson's favor. Davies argues prosecutors had always theorized at least four masked intruders wandering inside Evans' home the night of the murders. Thus, Jahn would simply be the fourth suspect in the equation. Regarding the prospect of a new trial, one of Nickerson's attorneys, Gerald Schwartzbach, all but says "Bring it on." A retrial of Nickerson would also mean a retrial of the case's two controversial chief investigators, Brian Beck and Jerry Hall. Unlike Nickerson, Beck and Hall have prospered since the 1984 killings. Both have been promoted from sergeant to lieutenant to captain. At one point Hall even ran the sheriff's training division. And Beck ran for sheriff--unsuccessfully--in 1998. Beck and Hall refused to be interviewed for this story. Both said it would be inappropriate for them to talk to the media because they may be called to testify in Nickerson's pending federal appeal. An internal Sheriff's Department memo obtained by Metro shows that some of Beck and Hall's colleagues believed the two detectives' actions violated the department's general orders and merit system rules. "The Internal Affairs unit is of the opinion," Sgt. Don Zies said in his Feb. 4, 1994, memo to then Sheriff Chuck Gillingham, "that administratively there appears that major violations did occur according to Judge Foley and court transcripts." As the legal machinations churn, Buddy Nickerson bides his time. Schwartzbach muses that his client was suffering from a peculiar affliction when he turned down a plea bargain in the early phase of his case. Like countless other criminals, Schwartzbach says, Nickerson had worked the system when he was guilty, cutting plea deals and massaging prosecutors and judges to serve the least time possible for his crimes. Naively, Schwartzbach says, many criminals assume that if they are truly innocent, the system will work and find them not guilty. Buddy Nickerson was one of those naive people. But Buddy Nickerson says he doesn't want people to feel sorry for him. "They should feel sorry for the justice system," he says. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the February 15-21, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2001 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.