Crowd Control

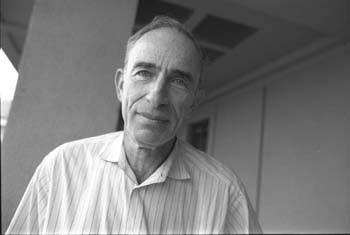

Dr. Doom: Stanford professor Paul Ehrlich says things have only gotten worse since he predicted, in 1968, that "we will breed ourselves into oblivion."

Paul Ehrlich, the avatar of birth control, insists that science, not politics, should determine the world's population policy

By Michael Learmonth

WHEN PRESIDENT CLINTON gave his State of the Union speech, he spoke of saving Social Security, training teachers and funding child care. Paul Ehrlich was disappointed. To make the Stanford University professor happy, all the president would have to do is to point his earnest squint into the camera and say, "Remember: responsible Americans stop at two children."

The author of the groundbreaking 1968 book The Population Bomb has been waiting a long time for an American president to make that statement, but he admits that it seems even less likely now than 30 years ago.

It would be a touchy statement to make, politically. Republicans' views on contraception are well known, and Democratic candidate-in-waiting Al Gore has four children. Clearly, the American political establishment shares little of Paul Ehrlich's concern, stated forcefully in The Population Bomb, that "we will breed ourselves into oblivion."

Ehrlich's office is on the fourth floor of the Herin Lab Building off the Stanford Quad in Palo Alto. Ehrlich is tall and intense and looks very fit. He has a piercing blue gaze and a very sharp tongue. Since becoming a biology professor at Stanford in 1959, he has mounted a 35-year study of the checkerspot butterfly. He's written 37 books and conducted research on every continent of the globe.

Ehrlich bursts out of his office soon after his secretary announces a reporter has arrived.

"I'm swamped!" he barks. "You have five minutes!"

Ehrlich is a man racing against time. It was Australia last week to study butterfly populations and Costa Rica next week to study the effects of wildlife fragmentation. Saving the world leaves little time for interviews. At one point, when asked a question about his work in Costa Rica, he refers it to an innocent graduate student pecking on a computer nearby.

"You can answer that, right?" he says, hardly slowing down.

In the years since Ehrlich's book was published, the world's population has grown from 4 billion to almost 6 billion. Yet his ideas are under attack from a small cadre of conservative social scientists who believe that Ehrlich exaggerated the problem. Some even charge that his ideas have led to human rights abuses abroad in the name of population policy.

In the early 1970s, the Malthusians--who follow the view of the early population biologist Thomas Malthus--clearly won the day, with dramatic predictions of spiraling fertility rates, famine and environmental collapse. Paul Ehrlich was their spokesman, teaching, delivering lectures and even appearing on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson 25 times.

But as the year 2000 approaches, it is the other side of the debate which has the American public's ear. They could be called "Cornucopians" for their belief that advances in technology will keep the earth plentiful. That group was led, until his death last week, by techno-optimist Julian Simon, who in 1980 made a $1,000 bet with Ehrlich that the price of five metals would decrease in the following decade.

Simon won the bet.

Population Implosion

THE POINT OF the bet was to prove that resources are not finite and we are not running out. According to Simon, Ehrlich's strictly scientific approach discounts what he called the "only real resource"--the human mind.

Two other widely published population optimists are Ben Wattenberg and Nicholas Eberstadt, senior fellows at the American Enterprise Institute. They are joined by the world's pre-eminent pro-natalist, Pope John Paul II, who regularly speaks out against contraception in countries with precipitous birthrates.

"Eberstadt and Wattenberg write as if they are totally clueless," Ehrlich says. "They're always wanting to build exemptions for ourselves from the laws of nature."

The optimists' argument, however, is bolstered by recent population data from the United Nations' World Population Prospects: The 1996 Revision, which downsizes previous projections and forecasts that the world will reach what's called a "replacement birthrate" of 2.1 children per woman by the year 2050, when the human population will peak at 9.4 billion. Conceivably, then, as birthrates continue to fall, world population will begin to decline.

The New York Times Magazine published an essay by Wattenberg in November, "The Population Explosion Is Over." In the Wall Street Journal, Eberstadt went so far as to warn of a "Population Implosion." In both articles, the authors express dismay about the decline of population in more affluent countries and argue that the aging, dwindling populations of the Western world are concerns equal to any population explosion in the developing world.

Italy (a Catholic country, Wattenberg reminds readers) has a birthrate of 1.2 children per couple. European birthrates are down around 1.4, the same as Japan's and Russia's. The U.S. rate is 2.0.

Even in the Third World, where birthrates are highest, the average numbers are falling. India's fertility rate is lower than American rates of the 1950s. Bangladesh has fallen from 6.2 to 3.4 in the last decade. Today, the world's birthrate is 2.8 and falling.

There are many theories to explain the decline: worldwide urbanization, increased education, the availability of contraceptives, more women in the workforce and delaying of marriage are known factors. But some scientists also believe toxics and hormones in the environment are reducing human fertility worldwide.

Reached in Washington, D.C., Eberstadt says that 30 years of focusing on population growth as the developing world's most pressing problem has caused regrettable human rights abuses.

"It gave excuses for unconscionable abuse of human rights in involuntary population-control programs in China and elsewhere," Eberstadt says.

In the 1970s 3.1 million Indian women were sterilized by force. The Chinese report that their vaunted population program has brought birthrates down to 2.0. A remarkable achievement, but stories of coercion and female infanticide in that country persist.

In some cases, says Eberstadt, developing countries focused on population as the problem while corrupt leaders plundered the economies.

"In much of the Third World, the constraint against development was all this chatter of the Malthusian sword hanging in the air," Eberstadt argues. "The drumbeat served to excuse irresponsible leaders."

The human rights abuses of the past have also affected public policy in the United States, he says. Incidents of compulsory abortion and forced sterilization reported in China have been used by the anti-abortion movement in the U.S. to discredit population programs.

Religious Reasons

HAL BURDETT, spokesman for the Population Institute in Washington, D.C., says the anti-abortion movement deliberately confuses abortion with contraception. Some people, he says, believe that any government-sponsored population-control program is a slippery slope to compulsory abortion. Yet outside the Vatican and fundamentalist religious movements, there are few who oppose contraception. "I think there are plenty of things that can be said for voluntary family planning," Eberstadt admits, placing the emphasis on "voluntary."

"Survey after survey reports the best predictor of fertility levels is the desired family size as reported by women," Eberstadt says. "Mexico has had a hugely celebrated national family-planning program for a generation, and Brazil has none." Yet, he points out, their birthrates have remained identical.

However, by associating family planning with abortion, religious fundamentalists have built a movement in Congress to oppose U.S. foreign aid for family planning in the developing world.

Burdett says 147 members of Congress voted to end all international population assistance, based on their anti-abortion ideology.

The pull of religious groups was felt in Sacramento last week as Gov. Pete Wilson vetoed AB160, which would have allowed the state's medical insurance providers to cover contraceptives such as the pill. Burdett says his veto came because Wilson wanted a greater "conscience clause" for insurance plans affiliated with religious institutions to be able to opt out of the mandate.

Linda Williams, director of Planned Parenthood in Santa Clara County, lobbied for the bill. She thinks a "conscience clause" as broad as the governor wants will allow plans to opt out "simply because they don't want to pay."

Paul Ehrlich is very familiar with the backlash against the movement he started. He and his wife, Anne, also a Stanford biologist, even wrote a book about it, In Defense of Science and Reason, published in 1996.

Ehrlich argues that since The Population Bomb was written, 300 million people have died of starvation, species extinction has accelerated and greenhouse gases have caused measurable global warming.

"We're like a profligate child," Ehrlich says. "We're writing a bigger check every year and never looking at the balance."

Incoming Numbers

EHRLICH BELIEVES that as long as the human population supports itself by spending environmental capital--overpumping aquifers, destroying species, clearcutting forests--and not living off the interest, the Earth is overpopulated. So why is the Cornucopians' argument so successful?

"People don't like the idea that there could be too many people," he says. "The Right is afraid that people will be told how many children they can have, and that's a government intrusion."

Ehrlich thinks the American people misunderstood the news in the mid-1970s when U.S. birthrates reached replacement level. While on average, American women have 2.0 children, U.S. population growth continues, driven by immigration.

Joseph Speidel, director of population programs at the Hewlett Foundation in Palo Alto, says the U.S. will add another 120 million to its current population of 268 million before leveling off.

"Unless population spending is increased, the numbers will not turn around because the generations becoming fertile are very large," Speidel adds. "I see a very difficult collision coming, and I'm certainly in the corner of Paul Ehrlich."

Ehrlich acknowledges that world population will ultimately stabilize and then decline. The question is when and how.

"Are we going to humanely limit births or accept high death rates?" he asks.

Diseases such as AIDS, ebola, the Hong Kong flu and mad cow disease are closely tied to population density. The higher the density, the easier it is for disease to spread quickly.

Ultimately, he says, an epidemic such as the one that spread from chickens to densely populated humans in Hong Kong could become a modern-day plague--nature's limit on population.

Ehrlich believes Americans are open to the idea of limiting population, but less so to changing destructive lifestyles. At a time when the fragility of the environment is becoming more apparent, he sees a new breed of "super consumers" revving up consumption with their big cars and greater affluence.

"Americans can be persuaded that families should be smaller," he says, "but try convincing them to consume less."

One billion of the earth's 5.9 billion make less than $1 a day. What if, Ehrlich asks, the Third World follows the same consumption trajectory as the U.S.?

Lying out in the reception area of Paul Ehrlich's office is a copy of Newsweek with a photograph of the McCaughey septuplets and their proud parents.

"One of my graduate students must have put it there," he says. Charging back into his office, he shoots back a half-smile, half-sneer, "You can imagine what I think!"

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Christopher Gardner

From the February 19-25, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)