![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

Buy 'River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West,' an Eadweard Muybridge biography by Rebecca Solnit.

Buy 'Time Stands Still,' the companion catalog for the exhibit.

Buy the 'Horses and Other Animals in Motion' collection of Muybridge's sequence photos.

|

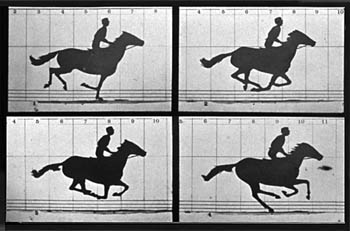

Stride and Seek: Four shots from Muybridge's 'The Horse in Motion' showed 19th-century viewers a new reality. Photo Mount Stanford traces history of Eadweard Muybridge's experiments with motion photography By Michael S. Gant THE CAMERA AS EYE works so well as a metaphor that we usually forget that the camera can show us what our eyes cannot. When photography was first invented, long exposure times dictated posed shots--and if the subjects couldn't sit still, clamps and braces held them in place. These early pictures preserved static images, but they didn't record life in the sense that life is a process as well as a state of being. Not long after the birth of the new medium, photographers sought to capture the flux of time by freezing it; they wanted to show motion in a single instant, without blurring. The result was known as instantaneous photography, and the history of this loosely defined moment--and its culmination in the work of Eadweard Muybridge--is the subject of a fascinating new exhibit called "Time Stands Still" at Stanford University's Cantor Center for Visual Arts. At first glance, a work such as Stuart Wortley's 1863-65 albumen print A Wave Rolling In reveals nothing special, but to his audience the foamy crest arrested in midcurl was a revelation. So popular was instantaneous photography that some shots were faked to create the illusion; an 1860 shot of a juggler is an elaborate ruse, with the balls planted in place by composite printing. In 1872, Muybridge, an Englishman who had immigrated to the United States and made his way to San Francisco, showed people an entirely new way to perceive reality. Working on a commission from railroad baron and racing buff Leland Stanford, Muybridge set out to prove that all four of a horse's feet leave the ground simultaneously at one point during a trot. Muybridge set up a bank of cameras to take photographs at a high speed (faster than 1/1000th of a second, he claimed) as Stanford's prized race horses tripped wires connected to the shutters. The images showed the hooves entirely off the ground at the same time, something no eye had ever been quick enough to confirm unaided. Even more intriguing was the sequence of photographs. Project them on a spinning disc that Muybridge called a zoopraxiscope, and the illusion of motion was created. Next step: cinema. In addition to a generous selection of Muybridge's motion studies with horses and other animals (goats, birds, dogs), people (acrobats, gymnasts, a man turning an orange in his hand), "Time Stands Still" also includes several of Muybridge's zoopraxiscope discs and a reconstruction of his projection mechanism that the viewer can hand crank to create a shadowy gallop across a darkened wall. The works of some of Muybridge's less-famous contemporaries contain aesthetic pleasures of their own. Particularly beautiful is Ottomar Anschütz's 1884 nine-image sequence of storks landing at their nest. The exhibit comes with a excellent book/catalog by guest curator Phillip Prodger (and published by Oxford) and a number of related events, including a slide talk (Feb. 20 at 7pm) by Rebecca Sonit, author of Rivers of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West, and a symposium (May 3). "Time Stands Still" also serves as a kind of belated restitution by the university. In 1877, Stanford published Muybridge's sequence photos as The Horse in Motion, but did not list Muybridge as the author. The photographer objected vociferously, and the collaboration with Stanford dissolved in rancor.

Time Stands Still runs through May 11 at the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, at Museum Way off Palm Drive. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays. Admission is free. (650.723.4177)

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the February 20-26, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.