![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Haiti on the Brink

With the island nation torn by armed revolt, Cinequest presents 'The Agronomist,' a timely new documentary about a heroic Haitian journalist

By Richard von Busack

Early one morning in Port au Prince, Haiti, on April 3, 2000, Jean Dominique, an agricultural adviser and crusading journalist, was shot four times with a 9 mm pistol. Nevertheless, the nation's first independent radio station, Radio Haiti Inter, reported Dominique alive and well three months later--a spirit walking among the people he died trying to serve.

The new documentary about Dominique, The Agronomist, by Jonathan Demme, arrives at an especially timely moment given the current upheaval in the dirt-poor Caribbean nation. (The film plays March 9 and 11 at Cinequest and opens in theaters in San Jose on April 30.)

Demme, best known for The Silence of the Lambs, is a noted patron of the visual arts of Haiti. He has also directed four previous documentaries on the island republic, including Haiti: Dreams of Democracy. The Agronomist chronicles the career of Jean Claude Dominique, whose life and times parallel his homeland's violent and seemingly never-ending struggle to bring democracy out of a swamp of despotism.

The president of Haiti is embattled Jean-Bertrand Aristide--the charismatic minister who at his best could be compared to Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela. But like Mandela, Aristide had to make the discovery that democracy isn't a given in a nation torn by severe inequalities.

Today, Haiti is again on the brink of civil war, with opposition gangs taking over in Cap-Haïtien, the country's second-largest city, leaving Aristide begging the world for aid, money and troops. By Aristide's count, there have been 32 coup d'etats in Haiti's history. The 33rd may be imminent, and the Haitian government is the first to admit it. "We are witnessing the coup d'etat machine in motion," Prime Minister Yvon Neptune told the Associated Press last week. Neptune himself is slated to be replaced under the terms of a very tentative U.S.-brokered deal floated over the weekend that would keep Aristide in power for two more years. So far, opposition leaders have rejected the plan.

Chimera Politics

Haiti has been a debacle zone for so long that the Haiti news doesn't lead, even when it bleeds. Check the Feb. 23 Time magazine article titled "A Battle of Cannibals and Monsters." The headline refers to the pro-Aristide Clean Sweep militiamen, who have been nicknamed "chimeras," just as some anti-Aristide vigilantes were formerly calling themselves the "cannibal army."

It all makes for picturesque prose. Despite decades of American occupation--despite the belief, as Aristide once put it in a speech, that "the wealth of Haiti has been, is, and always will be, stolen by the USA"--truly, Americans know almost nothing about the country.

The story of Dominique is a lens through which the story of the last 70 years of Haitian history can be seen. Demme filmed Dominique during some 15 or 20 sessions in New York in the 1990s, and the elderly agriculturalist-turned-journalist is almost curt when he stresses, "I'm not in exile, but away from home."

We see him as a bantam, wiry figure in his 60s, wearing a leather fisherman's hat and puffing on a curved tobacco pipe. There's a joke in broadcasting that some personalities have "a face for radio"--mellifluous voices are often attached to unphotogenic faces. On the contrary, it was too bad that Dominique wasn't on TV in Haiti.

The on-again, off-again owner, operator and guiding light of the independent radio station Haiti Inter was a real performer--a gesticulator with an unnerving fatalist's grin. The gesticulations, like the pipe, are traits he may have picked up in Paris, since his formative years were spent there as a student at the Institut National Agronomique.

Dominique was born in a well-to-do family in 1930, toward the end of Haiti's nearly 20-year-long occupation by the United States Marines. He recalls being told by his father to look away whenever the American soldiers were on parade. While the Marines built roads and hospitals, this infrastructure was accommodated with forced labor, martial law and suspension of the Haitian constitution.

Marine Gen. Smedley Butler was stationed in Haiti during the occupation that followed the intervention of 1915. Butler's memoir, War Is a Racket--essential reading--has been newly reprinted by the risk-taking small press Feral House. Butler won the Medal of Honor for being the CO at the Marines' attack at Fort Riviere, Haiti, Nov. 1915. Later, he characterized his hero's work on the island as "making Haiti safe for the National City Bank. ... I could have given Al Capone a few hints."

It was in this recently humiliated, puppet-run nation that Dominique grew up. His father was an importer/exporter who took his son to the interior to meet the farmers who grew sugar, coffee and cacao, which spurred the young Dominique's interest in agriculture. "I am not a journalist," he exclaims. "I became a journalist. I am an agronomist."

While studying botany, he also became a cinema buff. Dominique reckoned that his homeland, which was more than half illiterate, could be enlightened by movies: "If you see a good film correctly, the grammar of the film is a political act." After returning home from Paris, Dominique began a film society, which brought the works of Fellini and Alain Resnais to Haiti. Dominique even made a short film (Mais, Je Suis Belle, 1961), a sarcastic documentary about a beauty contest. This was the first Haitian-made film production on the island.

The influence of French director Alain Resnais (Hiroshima Mon Amour, Last Year at Marienbad) on Dominique is clearer when The Agronomist shows a snippet from Resnais' Holocaust documentary Night and Fog. The Resnais passage explains how the Nazis disguised their killing factories as ordinary factories; Demme fades in a similar shot of Fort Dimanche, an ordinary building where Papa Doc Duvalier's soldiers did their murdering.

It was, Dominique explains, a screening of Night and Fog that led the Duvalier government to ban his film society. This began a series of arrests and forced exiles for Dominique. Still, he outlasted two of the most infamous figures Haiti ever produced.

Like Father, Like Son

As the story goes, Columbus tried to describe the island of Hispaniola to Queen Isabelle by showing her a crumpled a piece of paper. Despite the island's sharp hills and deep valleys, Columbus was able to exterminate the native Arawaks in just over a generation.

France colonized the western half of Hispaniola and brought in slaves, who stripped the vegetation to make way for sugar plantations. Haiti's first national hero, Toussaint L'Ouverture, rose up and fought off Napoleon's troops in 1804, establishing the first African republic, in accordance to the same principals that sparked the French revolution. L'Ouverture's rebellion terrified United States slaveholders in the South and led to the creation of Liberia in Africa, as a homeland for repatriated slaves.

As in Liberia, Haiti's history is a story of conflict between a small class of mixed-race merchants and judges vs. the interior of the island, which is black and poor. In the last century, the old conflict was worsened by savage excess of the father-and-son team of tyrants who ran Haiti from 1957 to 1986: President for Life François "Papa Doc" Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude.

"Papa Doc" Duvalier had been a humanitarian doctor in his youth, but after taking over after a coup, he determined to wrap himself in the trappings of divine authority. This is why one observer, David Hawkes of Lehigh University, has noted that "visiting Haiti is as close as you could come to visiting medieval Europe."

Some points in favor of that argument: road conditions, lack of technology and the personality of Papa Doc. Like Henry VIII, the elder Duvalier dismissed clerics he didn't like, replacing them with his own hand-picked priests, which got him excommunicated from the Catholic Church (which had to be all the more insulting since Papa Doc once had a state portrait made of himself standing at the right hand of Jesus Christ).

But practitioners of the parallel religion of Haiti, voodoo, also had reason to fear Duvalier, who liked to attire himself in the top hat and swallowtail coat of the voodoo Baron Samedi: the lord of the crossroads, a powerful, occasionally lethal deity.

Actually, standing behind Duvalier's shoulder was not Jesus, but Uncle Sam, who tried to keep him in line with the stick (by cutting off foreign aid in 1961) and the carrot (recognition of Duvalier as an unsteady but vocal opponent of our Caribbean nemesis, Fidel Castro).

Duvalier kept power through his private army of secret police. Readers of Graham Greene's novel The Comedians still shudder at the ominous Tonton Macoutes--"Uncle Boogeyman"--the Duvaliers' fearsome secret police. During the Duvaliers' reign, anywhere from 20,000 to 50,000 people were their victims; the escape from poverty and violence led to a drain of talent weakening the nation.

It was this legendary tyrant that Dominique began to oppose with Radio Haiti Inter. Sometimes the dictator's methods were harassment, like urging the advertisers to pull out. The station was rescued by Richard Brisson, the head of programming, who loaned out his car as a taxi to bring in extra funds. Sometimes, Duvalier's intimidation was more characteristically direct, as in the arrest and beating of Brisson.

At death, "Papa Doc" was succeeded by his son, "Baby Doc," commonly referred to as "Baskethead" because of his huge yet empty skull. Baskethead's ascension, and the harvest of years of corruption, began what Dominique calls "The Haitian Spring," during the era of Jimmy Carter.

Even if the flag-waving hit Miracle posits the Jimmy Carter era as a time of failure, there ought to be a counterpoint. The rebellions in Nicaragua and Iran may have been U.S. foreign policy defeats, but to those under the thumb of President for Life Baskethead, these revolutions were signs of hope.

Carter's focus on human rights energized Dominique; we see footage of the Haiti Inter report on the assassination of Nicaragua's dictator, Somoza, where the reporter editorializes, ever so slightly: "They say Somoza's body had to be scraped off the ground"--a message in code to the Duvalier-blighted audience in Haiti that said, "Sic semper tyrannis."

The election of Ronald Reagan encouraged Baskethead and his Tontons to engage in further repression. Government forces shot up the Radio Haiti Inter building and broke in to smash the facilities. Dominique had to flee the country, like 2 million other Haitians, often in overcrowded refugee crafts heading for America. (And it is the fear that another exodus is in the making that drives the call for some kind of American intervention in the current crisis.)

Over the course of the next 20 years, Haiti endured a selection of different governments. Aristide was democratically elected in 1990, only to be replaced on Sept. 30, 1991, by a military junta, led by Gen. Raul Cedras, and two fellow alumni of the infamous U.S. Army School of the Americas at Ft. Benning, Ga. Then Aristide was re-established with the help of a 1994 invasion of 20,000 U.S. troops. Clinton's "achievable and limited" intervention achieved the extraction of Cedras and his partners.

Through these changes of political fortune, Dominique and Radio Haiti Inter continued to report fearlessly, even venturing to take on Aristide. The agronomist-turned-journalist has maybe his most acerbic moment grilling Aristide on the air. The sequence was not just a rare moment of Haitian democracy, it was a significant turning point for the relations between Aristide and Dominique.

Risking the Truth

Now, as Haiti marks its bicentennial, the country is in flames for all the old reasons. Foremost is its dire poverty--80 percent of the country is poor, with a life expectancy of 51 years, thanks to raging rates of HIV and AIDS. In this nation of farmers, only 20 percent of the land is arable, thanks to centuries of deforestation.

Clifford E. Griffin, an assistant professor of political science at North Carolina State University who spent time researching Haiti at Palo Alto's Hoover Institute, suggests a few reasons for Haiti's troubles.

The current violence is tangled in the history of the nation. "Democracy cannot plant roots in a field where employment, food, health care, education and other physiological necessities continue to be unavailable or in short supply," Griffin notes. "These are the issues that should be immediately addressed."

Griffin suspects that among the reasons for U.S. reluctance to save Aristide again is American suspicion of his liberation theology. Aristide is currently under financial stress, since the United States cut off foreign aid to Haiti following a dubious election on the island in 2000. And Aristide's particular headache is his old class enemies, who are well armed. These are the rich families who run Haiti, and their guards, the Tonton Macoutes and police who still have their arsenals from the old days.

Against this dolorous backdrop, Dominique's story deserves a truth-is-marching-on happy ending, but unfortunately, the reality is not optimistic. Reporters Without Borders details the aftermath. Dominique's widow and fellow reporter, Michele Montas, was hit with an assassination attempt in December 2002, in which her bodyguard was killed.

On Feb 2, 2003, Montas shut down Radio Haiti Inter out of fear for her life. She's currently in exile in the United States. Nor does the investigation of Dominique's death give cause for hope. One suspect was lynched in front of the investigating judge, who in turn fled the country. Witnesses have turned up dead under bizarre circumstances.

And no one seems eager to come to Haiti's rescue. The U.S. military is currently busy holding down Iraq and Afghanistan, and Colin Powell has claimed, "There is frankly no enthusiasm right now for sending in military or police forces" to Haiti. While France may dispatch a strike force to Haiti from its other Caribbean colonies, the situation is a nightmare with little signs of solution.

"The United States has played right into the hands of those who would re-establish the status quo [before] Aristide," Griffin states. "And that seems to be what's on the horizon. The reality is that Haitians will be taking to the seas again. Already some have landed in Jamaica, where the government has begun to draw up contingency plans. They will head for the Bahamas as well; and they will head for Miami. And many will not make it."

The last armada of boat people ended with thousands of Haitian refugees interned at the U.S. base at Guantanamo Bay. The worse-case scenario could be a humanitarian crisis right when the world can afford it least. Since Haiti has become a spot too dangerous for journalists, the crisis could take place largely in the dark. Only the kind of bravery demonstrated by Jean Dominique will get the story out.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

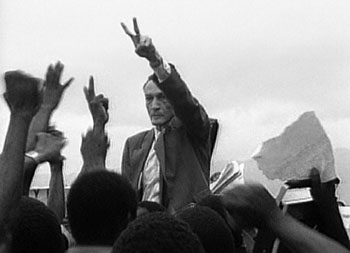

Victory Rallying: Jean Dominique used his role as a journalist to oppose repression in his homeland.

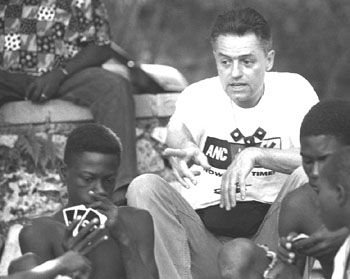

Director at Large: Jonathan Demme at work in Haiti.

The Agronomist plays Cinequest March 9 at 7pm and March 11 at 9:30pm at Camera One in San Jose. The film opens in theaters April 30.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the February 25-March 3, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.