![[Metroactive Stage]](/stage/gifs/stage468.gif)

[ Stage Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

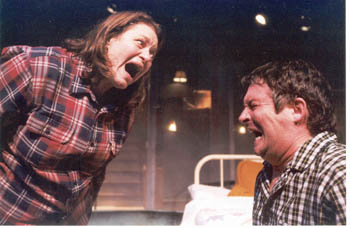

Photograph by Dave Lepori Fan Clubber: Annie Wilkes (Kathleen Stefano) has a crush on novelist Paul Sheldon (Patrick Lawlor) in all the wrong ways in 'Misery.' Royal Terror San Jose Stage ratchets up the terror in stage version of Stephen King's 'Misery' By Marianne Messina AT A RECENT San Jose Stage production of Misery, based on the Stephen King story, gasps, groans and oh-no's abounded. One's cringe muscles start clenching as soon as author Paul Sheldon (played by Patrick Lawlor) tries to move his legs and screams in excruciating pain. Paul becomes increasingly helpless while his tormentor, a nurse who has dragged him from his crashed car to her secluded home, becomes more irrational and sadistic. It's a great setup, and actress Kathleen Stefano, who plays the nurse gone wrong, makes a fearsome (and appropriately towering) Annie Wilkes. Annie's enigmatic character consumes the two-character play. All those quirky lines: "If I stay here, I'll do something unwise"; "You know I love you, don't you?" she says, hugging Paul (after a quiet discussion about killing him), followed by "I don't feel real, I don't feel real, I don't feel real"--yikes. So consistency is not Annie's forte, but she does have some recurring themes--her well-articulated religious rightness, for example, which the production doesn't underscore, except for a crucifix, some votive candles and an opening tableau of Annie praying. The cleverness of other theatrical elements, especially the active lighting, makes up for minor oversights. For light designer Michael Walsh, darkness is an option--and director Kit Wilder has things go bump in it--so it becomes a presence quickly animated with our own phantoms. In the tense scene where Paul explores Annie's backrooms (normally obscured behind a scrim), the narrow beams cast by shade lamps circumscribe one room after another as Paul make his progress, always surrounded by pregnant darkness. In the small, quiet moments, Stefano doesn't always seem at ease in Annie's skin, and there are times when the right touch of vulnerability could take the audience's sympathies and twist the proverbial knife. Nevertheless, her Annie is powerful, expanding especially well into large emotional spaces, as when she out-screams Paul. She also manages a nice blend of childlike narcissism and clutchy desperation. As for Paul, spending most of the play terrorized and helpless knocks the legs (pardon the pun) out of his emotional palette. Lawlor's Paul, while grinding nerves in his agony, can be bewilderingly light, even comedic. He never gives us the sense that this inverted-power nightmare reflects some dark dynamic inside himself, which seems to be suggested by the text. "You failed at just about everything, except for misery," Annie tells him. She also reminds him that "people in stories don't just slip away. You're in charge; you're God." Even Paul's dreams suggest that he's somehow in a world of his own creation, which is an especially eerie concept in light of the fact that years after writing the book on which this play is based, King was similarly maimed and debilitated in a back-road accident. Like most King creations, the play is loaded with archetypal fears, for example the Icarus dread--fly too high, you hot-shot author, and you'll get burned. Shudder.

Misery, a San Jose Stage production, plays Wednesday-Saturday at 8pm and Sunday at 2pm through March 14 at the Stage, 490 S. First St., San Jose. Tickets are $28-$38. (408.283.7142)

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the February 25-March 3, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.