![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

The Camerman Delivers

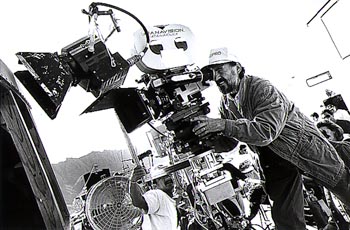

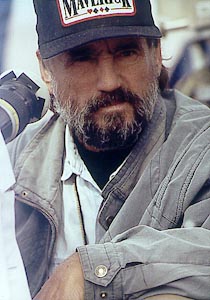

Photos by Andrew Cooper A talk with legendary cinematographer and Cinequest honoree Vilmos Zsigmond There's an old joke from the '30s about a sign on a movie studio wall reading "It's not enough to be Hungarian. You have to have talent." The joke refers to how a relatively small country had such an impact on the history of the movies. Just check some of the names: Michael Curtiz, Alexander and Zoltan Korda, Bela Lugosi, Andre de Toth, Laszlo Kovacs, Adolph Zukor. You can look up their individual bios, but the name of Vilmos Zsigmond, at the end of most cinema encylopedias, is one of the greatest. An Oscar winner for his cinematography for Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Zsigmond was also the first cinematographer to use the Panaflex camera on a movie--The Sugarland Express. Throughout the '60s, Zsigmond worked on psychotronic movies for Arch Hall Jr. and Al Adamson. He's uncredited on the gorgeously photographed and even more gorgeously titled The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies (a sentimental favorite because the long since demolished amusement park Nu-Pike in Long Beach lives forever in the film, as fresh as morning). His later career stretches from small-budgeted classics by Robert Altman--The Long Goodbye and McCabe and Mrs. Miller--to the later ambitious epics such as The Deer Hunter and Heaven's Gate. At Cinequest San Jose Film Festival, Zsigmond will appear on Feb. 28 at a screening of John Boorman's Deliverance, about the revenge of a group of citified sportsman who are badly used by a some backwoodsman. In an interview shortly before his death, author James Dickey said that the fear Deliverance inspired was the century's main fear: "The fear of groups of strangers doing one harm." Once seen, you can't get Deliverance out of your mind. It's shock is due to Boorman's imagination and Ned Beatty's emoting of terrible humiliation--but it's especially due to the haunted verdancy of the land Zsigmond photographs, as beautiful as it is dangerous. Metro: Was it your choice to screen Deliverance as part of your tribute at the Cinequest? Zsigmond: No, it wasn't really my choice. I have a lot of pictures, but it's one of the best films I did. They chose it because it's not been shown for a long time. Metro: Have you ever gone camping since you made it? Zsigmond: Not in that part of Georgia, no! Metro: Was Deliverance your first time away from the studio? Zsigmond: I would say yes. I don't think there's a scene set in a studio. Even the house they lived in where Voigt has his nightmare, that was a location. Metro: How did you become a photographer? Zsigmond: When I was a kid, I took snapshots with my father's camera. When I was sick once, I got as a present a book on photography by the best photographers of Hungary. I became a photographer first and then a cinematographer. I came to the U.S. in 1957. Metro: Do you find yourself watching movies for the photography alone? Zsigmond: I try not to, I try to be absorbed by the story. I don't want to ruin the experience. Obviously, if I'm seeing what the cameraman done, I'm not really concentrating. I have to watch a film twice, once for the content, and once for photography. Metro: You've worked on some notoriously troubled sets, for Heaven's Gate, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the aptly titled Jinxed!.

Zsigmond: Probably Jinxed! was the most difficult. The story was sort of comic, so was Don Siegel [Dirty Harry] the best choice as director? The trouble was that he was terribly ill by then. Basically he was dying of cancer when he was doing the movie, and during the day he slept hours and hours. He told me to take extra time for lighting, so he could sleep. Close Encounters was difficult because of the lighting. We had huge amounts of lighting to get the special effects--it's all what would be done by CGI today, but in those days we had to do it in the camera. For The Deer Hunter, we were traveling all over the world. Heaven's Gate was one of my best movies, and it wasn't difficult. The studio had trouble with it, though, and wouldn't stand behind the movie. The audience really enjoyed it for the beauty and authenticity of it. Metro: Your first popular film was Deliverance when you were in your early 40s. Were you worried about your career? Zsigmond: No. My first 10 years in America were difficult, but when I was hired on by Altman for McCabe and Mrs. Miller and The Long Goodbye, I knew things were going to happen to me, even though the Altman films weren't big studio pictures. In those days, a big-budget picture was $2 million. We made Brain De Palma's Obsession for $800,000. I got half a percentage point in the film, and it still brings in money. Metro: What's the principal difference between filmmaking now and filmmaking then? Zsigmond: In those days, nobody asked questions of the director. When Altman was making The Long Goodbye, it turned out that the producers didn't like the dailies. They especially didn't like the scene where Mark Rydell takes off his clothes. The producers told him to reshoot it, and Altman vanished. Nobody could find him for days. And finally they found him and asked what the matter was? And Altman said, "What's the matter? I'll tell you what the matter is, you didn't like the dailies. I'm not directing again until you like the dailies." Finally they gave in and told him, "We like the dailies." The next day we started shooting again. Metro: While the storytelling in movies isn't impressive currently, the photography is commonly very good. Zsigmond: My point is that in all stories, even bad stories, there's a story be told. The cinematographer can make it a successful story by changing the mood of that movie, by telling the story it was meant to be told. Often he's more successful at the storytelling than the director or the writer.

Vilmos Zsigmond: A Master of Light takes place Feb. 28 at 2pm at the UA Pavilion Theatres.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

Web extra to the February 25-March 3, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.