![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

Buy one of the following Rudy Ray Moore DVDs from amazon.com: 'Dolemite' (1975) 'The Human Tornado' (1976) 'The Dolemite Collection' (a seven-disc box set)Buy one of the following books related to this article: 'Dolemite: The Story of Rudy Ray Moore,' by David L. and Julian L.D. Shabazz. 'Mules and Men,' by Zora Neale Hurston. |

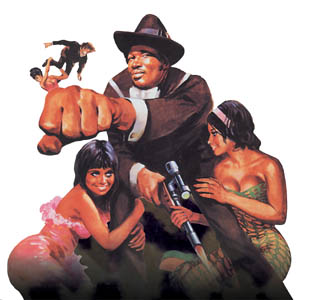

Mojo Man: Rudy Ray Moore puts his best fist forward in the poster for 1975's 'Dolemite.' Monstrosious! Rudy Ray Moore and 'Coonskin' at Cinequest: the black hero of the 1970s on the fringe THE LONGTIME fascination of white people with street styles of the 1970s has reached a zenith. Now, and this is when culture vultures really get to feast, it's heading into the baroque stage. Every Iowa college dorm's "Ho and Pimp" party, every high school kid's deep-held conviction that he is really Huggy Bear, are just now starting to become passé. The joke is wearing off. Two nails in the coffin: 1) The soon-to-be-released Sony Pictures feature-length cartoon Li'l Pimp, based on Peter Gilstrap and Mark Brook's MediaTrip.com Internet cartoon about a freckled boy who also runs a pair of hookers. 2) Diva Starz dolls (remember last Christmas?), tricked out in what once would have been called 42nd Street evening wear. By now, an adults-only stereotype has become, in essence, a toy for kids. This year's Cinequest hosts two of the most rarified extremes of the wave of the pleasure-man in action. The remarkable career of Rudy Ray Moore, R&B singer and actor, is chronicled in San Jose director Ross Guidici's documentary The Legend of Dolemite: Bigger and Badder. Animator Ralph Bakshi will be on hand (March 8) for a screening of his 1975 outrage, Coonskin. Moore's berserk films played to mostly all-black audiences in the 1970s, garnering reviews like "This film isn't fit for a blind dog to see!" Coonskin, which debuted in New York to the sound of angry protests and played in theaters struck with smoke bombs, is a now-unthinkable tirade against white manipulation that played black people against each other. These films show how much more there was to black film in the 1970s than strutting pimps and tube-topped hookers. The world premiere of The Legend of Dolemite: Bigger and Badder (Feb. 28) is occasioned by Xenon Films' release of a seven-picture box set of films starring Rudy Ray Moore, a.k.a. Dolemite. Xenon's first video reissue was Melvin Van Peebles' early black-hero film Sweet Sweetback's Baad Asssss Song (1971). Van Peebles (father of actor Mario) owns part of Xenon. Xenon's Steven Housden, co-producer of The Legend of Dolemite, says, "We were doing urban before it was called urban. We also do the odd documentary." He lingers over the word "odd." The Legend of Dolemite is Guidici's first documentary. Guidici, a self-descried "Nebraska Sicilian," attended Blackford High in San Jose and De Anza College. He started out as a stand-in for Charlie Sheen in the Clint Eastwood film The Rookie (which was shot in San Jose). Since then, he's worked in various capacities in scores of movies, mostly as an editor. Guidici had never heard of Dolemite when he was hired to work on the documentary, a completely revised and updated version of a Dolemite documentary Xenon put out in 1994 (hence the subtitle, Bigger and Badder). Many of Moore's fans are interviewed, including the Beastie Boys, Eddie Griffin, Robert Townsend and Snoop Dogg, who says he saw Moore's 1975 film debut, Dolemite, "300 times." Guidici's film suggests that Moore's work on his self-made party albums of the late 1960s and early 1970s presages the ascent of rap. Moore himself says, regarding rap, "I was through with it before they knew what to do with it." Moore's late-1960s spoken-word album Dolemite provided the nickname he used on several albums and movies. Dolemite sounds like a nutritional supplement, but as cinema it's candy. In the role of "Dolemite" in five films, Moore toyed with the idea of the African American hero. His playful self-stereotyping differs completely from the image of the austere street soldier of today. Love Power The first shot in 1976's The Human Tornado, a.k.a. Dolemite 2, is a close-up of a spinning disco ball. Is everything that follows just a hypnotic delusion? Kidnapped by Mafia nightclub owners, cocktail waitresses TC and Java are tied up and groped by a midget granny in a foot-tall wig made out of a dirty mop. The old witch menaces the girls with a small and uninterested python. Java is played by a person identified on the Internet Movie Database as Lord Java. If she is indeed a female impersonator, she sure beats Jaye Davidson of The Crying Game. Is this the same Lord Java whose arrest by the LAPD at Redd Foxx's comedy club in 1969 resulted in a famous test case by the ACLU? Maybe, but in another matter the ACLU ought to have looked in on, Java lies prone under a hanging bed of spikes supported by a rope that is being burned slowly by a candle flame. The infernal device looks exactly like the death trap seen in a famous 1931 Betty Boop cartoon Bimbo's Initiation. It's more frightening in the cartoon. Our two uncomfortable hostages can only be saved by Dolemite himself, but the hero of our nation's ghettos is taking his own sweet time. First, he must get directions to the dungeon by interrogating Mrs. Cavaletti (Barbara Gerl), wife of one of the hoodlums. Dolemite beguiles her by posing as a door-to-door salesman of erotic black-velvet paintings. The love power of the amazing Dolemite wreaks a midorgasm confession from the white woman. What could only be described as seismic shock waves of Dolemite's mojo literally shake the room to pieces, causing the lights to flicker on and off, the bed to spin like a top and the ceiling to collapse. This is the watershed moment in the film. From then on, Mafia nightclub owners and cracker Southern sheriffs alike must retreat, outwitted by kung fu and soul power. Dolemite himself is invincible, for, as he tells the camera, "Mule kicked me and didn't bruise my hide /A rattlesnake bit me and crawled off and died." The excerpts of Moore's films seen in the documentary should make instant fans out of viewers. If India's Bollywood rates credit for being a masala of action, music and comedy, Moore and his regular director, Cliff Roquemore, similarly deserve some kind of nod for their everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach to moviemaking. The Devil's Son-in-Law Raised in Fort Smith, Ark., Moore worked as a singer and what he calls "adagio" (male exotic) dancer in Cleveland. While there's loads of nudity in Moore's films and on his record covers, it's not all male-gaze provocation, as Dolemite runs around in his movies ass-naked, too. Moore recorded for King Records, the Cincinnati label that was the home of R&B legend Wynonie Harris. As a singer, Moore went to L.A. in the mid-1960s, cutting the single "Rally in the Valley" for the Vermont label. Somehow the shadow world of "party records" reached out to Moore. These XXX-rated comedy records went far beyond what was allowed on the radio of the time. Moore started by selling them out of the trunk of his car but eventually got enough cachet from them that they led to the movie version of Dolemite, directed by the grave actor D'Urville Martin. Moore was toiling square in the center of the golden age of what came to be called blaxploitation. The era included a range of black images in popular film, from mainstream dramas like The Best Man, with James Earl Jones as the first black president, to The Legend of Nigger Charley, with Fred Williamson as an escaped slave in the Old West. A black Dracula, or "Blacula," if you will, was twice played by the kingly Shakespearean thespian William Marshall. Nineteen seventy-two was the year of Superfly, as well as sequels to both Shaft and Cotton Comes to Harlem. The first and only time James Bond became aware of race prejudice was in the wretched Live and Let Die (1973). The same year, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes offered a race-war allegory thinly veiled as a monkey movie. This was a broad stratum of cinema, and yet what we think of as blaxploitation specifically means a film that's about a tough hombre or private detective going up against white corruption. But "blaxploitation" is a lousy term, anyway, one that black people didn't invent. Something always "exploits" (sells) a movie, whether it's youth or sex or war or comedy. The popularity of the black films of the 1970s has one explanation. What we think of today as classics of a newly mature, morally complex American cinema, such as Robert Altman's films and Chinatown, were rough experiences for a strictly entertainment-seeking audience. As Pauline Kael noted in her praise of the actioner Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold, "The movies for blacks have something that white movies have lost or grown beyond. ... It's a lost paradise of guiltlessness." What Moore calls his "monstrosious" success produces an interesting contrast to the vision of the all-powerful black hero in 1970s movies. The more dignified could call Dolemite movies bufoonery, but he's not a buffoon--he's the hero. What's going on here? Here's a clue. At the beginning of Petey Wheatstraw, the Devil's Son-in-Law (1978), Moore looks at the camera and recites a rap he probably figures the audience knows by heart: "I'm Petey Wheatstraw, the devil's son-in-law, the high sheriff of hell." Born during a Miami hurricane, he was so bad he slapped the doctor who delivered him. Satan recruits this man among men, because he craves a father for his grandson. A version of the Wheatstraw story occurs in 1935's Mules and Men, a narrative collected by author Zora Neale Hurston, who is currently starring on a U.S. postage stamp and is the subject of two new biographies. Hurston, an anthropology student working with Franz Boas, collected spoken-word stories at small towns and turpentine-harvesting plantations in Florida. Her book is to black humor what Allan Lomax's field recordings of the 1940s are to the history of blues, gospel and field music. Writing down rhymes and recitations, Hurston dug up the roots of rap. One of Hurston's correspondents tells the story of John, who had Satan as a father-in-law. The way Hurston tells "John and the Devil," the story is akin to Rumpelstiltskin. Lucifer sets impossible tasks, and "Beatrice Devil," the devil's pretty daughter, outwits her dad and saves her new husband by performing all the tasks for him while he sleeps. "[John is] the great human culture hero in Negro folklore," Hurston wrote in 1935. "He is like Daniel in Jewish folklore, the wish-fulfillment hero of the race. The one who, nevertheless, or in spite of laughter, usually defeats Ol' Massa, God and the devil." For "John" read Dolemite. Anti-Idiot By coincidence, Ralph Bakshi also tweaked old folklore for his most notorious film. Uncle Remus was the creation of a white Indianan named Joel Chandler Harris. Harris, who lived in Georgia during the Civil War, was an ear-witness to slave folktales. When Harris moved north, he published a popular series of funny-animal stories. These were uncute, violent tales, closer to Itchy and Scratchy than to Mickey and Donald. In 1947, Disney made Harris' stories into Song of the South. Disney's combination live-action and animated movie is still under de facto domestic ban by the Mouse, though it sells overseas. The magic moments that keep it banned include what critic Richard Schickel describes as "a finale in which the darkies gather round the big plantation to sing one of massa's children back to health ..." In Bakshi's view, this Disney film made a perfect target. "It's ridiculous!" Bakshi growls. "You just did a picture of happy slaves, walking home in the sunset? Are you out of your fuckin' mind? How could you do that?" Bakshi, now an artist living and working in the Southwest, was an animator for more than 40 years. He spent his youth in Brownsville, Brooklyn. In 1972, he directed Fritz the Cat, nominally based on R. Crumb's comics, though Crumb loathed the result. It was the first full-length X-rated cartoon produced in America, all about a hustling cat who slides through the youth movement trying to get laid. "None of my pictures were anything I could ever take my mother to see," Bakshi admits. "You know it's working if you're making movies you don't want to your mother to see." Coonskin has received scant distribution, although it deserves critic Leonard Maltin's judgment: "It remains one of his most exciting films, both visually and conceptually." In Coonskin, Bakshi plays with the stereotypes in a way that still makes audiences uneasy; not until Spike Lee's Bamboozled would there be such a sonata on themes of black images at the movies. "The art of cartooning is vulgarity," Bakshi asserts. "The only reason for cartooning to exist is to be on the edge. If you only take apart what they allow you to take apart, you're Disney. Cartooning is a low-class, for-the-public art, just like graffiti art and rap music. Vulgar but believable, that's the line I kept walking." Coonskin unfolds as a series of vignettes, loosely threaded on the adventures of Brother Fox (voiced by the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Charles Grodone), Brother Bear (soul moaner Barry White) and Brother Rabbit, better known as Bre'r Rabbit (the name is a Harris contraction). They escape the country and go to Harlem, seen in live-action background shots photographed by William Fraker. The film is almost anti-humorous; expect a walk out or two during the scenes about a minor character is trying to seduce Miss America, a red-white-and-blue-clad giantess who sexually humiliates him and then crushes him. Bakshi also includes references to the Liston-Ali fights, with Brother Bear sold out to the mob, as Sonny Liston was. (Modern audiences will probably object most strongly to the gay stereotypes.) The angriest part of Coonskin is a sequence that castigates The Godfather; an uncredited Al "Granpa Munster" Lewis does the voice of the Don, a red-eyed warthog. The sequence is like some of Lenny Bruce's extreme routines, where the satitist's rage is more palpable than the humor. The film's producer was Albert Ruddy, who also produced The Godfather. Bakshi says that although Ruddy was "fine" with the satire, it also seems that no one really knew what Bakshi was up to as he worked on the film. "I told them I wanted to make the Uncle Remus stories," Bakshi said. "And then I started to make my film. No one's got time to hang out with an animator; you're not going to sit there seven days a week, so it can be very subversive work. I was making fun of the black exploitation movies, the ones where if you're white, you're dead. Every one thought the picture was going to be anti-black. I intended it to be anti-idiot." Even before release, Coonskin was branded as an Amos and Andy-style insult and earned hostile reactions before it was officially released. "We were showing Coonskin at the Museum of Modern Art," Bakshi remembers, "and the Committee [on] Racial Equality [CORE] surrounds the building. The protest's leader was the young Al Sharpton, still a kid. I asked Sharpton why he didn't come in and see the movie, and he announced, 'I don't got to see shit; I can smell shit!'" After Paramount Pictures unhooked itself from the film, which played in New York, it was reissued under the vague title Streetfight. Bakshi finds that people still watch it. It probably got him hired to do the Harlem Shuffle video for the Rolling Stones. "Spike Lee is a big fan of Coonskin," Bakshi says. "I get emails from new fans all the time on it. Some can't believe I'm white." It's easy to immerse oneself in nostalgia for these loose films, made by Bakshi and Moore, of a world before crack and AIDS, mandatory-sentencing laws and ghetto neglect. Moore's outrageousness and Bakshi's willingness to say what he felt like saying, at the risk of fomenting outrage, seem like extinct qualities. Bakshi says, "I'm 65 now. I have less of the fury you feel in Coonskin. But now I realize there's a lot more wrong with the world than I ever guessed at the time." Rudy Ray Moore sums up his attitude in Guidici's documentary: "Although I am great, I'm not conceited in my greatness. I'm just convinced." A new generation of artists couldn't ask for a better motto.

The Legend of Dolemite: Bigger And Badder screens Feb. 28, 11pm, C3; additional screenings March 1, 7pm, C3 and March 2, 9pm, C7. An Evening With Ralph Bakshi: A World Of Color And Imagination takes place March 8, 5pm, C1, and includes a showing of Coonskin.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the February 27-March 5, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.