![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Paved With Velvet

Road to Ruin: Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) takes a ride with no return ticket down David Lynch's "Lost Highway."

The violent ones shall inherit and corrupt the meek in David Lynch's demon-haunted new film, 'Lost Highway'

By Richard von Busack

DAVID LYNCH describes Lost Highway as a "Möbius strip"--a symbol of infinity, apparently two-sided but really one continuous plane. The film looks to be in two halves, but Lost Highway is not about amnesia, or double identity, but dislocation--of being expelled from one's own identity.

At the center of the puzzle is a figure called the Mystery Man, but Lost Highway isn't a tale of ordinary demonic possession. Compared to what goes on in here, ordinary demonic possession would be merciful. In his later movies--since Blue Velvet--Lynch has often worked with the motif of devilry. But the Prince of Darkness doesn't come looking for souls; when a devil turns up in a Lynch movie, it's usually just because he likes to watch.

Lynch and his co-writer, Mark Frost, built the TV show Twin Peaks with a demon named "Bob" as one of the main characters. Bob's chief, the Little Man From Another Place, turned up in both the series and the highly underrated big-screen prequel, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992).

Like a gangster stiffed of his cut from a robbery, the Little Man tells Bob, in a translating subtitle (because he uses a word possibly from the native tongue of demons), "I want all of my garmonbozia [pain and suffering]." Lynch's demons feed off of pain and suffering. We are perhaps kin to them: we watch the pain and suffering of others, using them for our own purposes.

There is no real subtext in a Lynch movie, because his films are all subtextual. Discussing what happens in one of them is thus almost a matter of opinion rather than a matter of fact. His narratives start with ordinary movie premises but quickly move away from logical explanations. Lost Highway is a horror film thinly disguised as a crime drama with a plot that resists analysis; the wraparound story, like that of 12 Monkeys and La Jetée before it, begins where it ends.

Effects of lighting and sound sharpen the sense of disorientation throughout Lost Highway. Angelo Badalamenti, Lynch's usual musical collaborator, creates low tones that are like a psychological-warfare version of Sensurround, sometimes punctuated with the tones of a grind-house saxophone, electronically treated to sound like ocean-liner klaxons.

Lynch's actors give masklike performances and utter deliberately misreadable lines (does a character suffering in jail yell, "Guard!" or "God!"?) The images white-out into a burn--or brown-out into oblivion.

Lynch's films are often without deep subject matter--and yet they affect you on a deep, emotional level. Like a bad nightmare, they color your whole day. His obsessions surface again and again: the first discovery of sex; force and those who use it; the persistence of the most vicious sexual fantasies in the meekest people; and the way that the violent and the meek, when brought together, nourish voyeuristic demons avid to suck up some garmonbozia.

Scenes that might have been bits of everyday exploitation are turned by Lynch into pure horror. He gives you what you want to see, and seeing it makes you realize the demon within.

Trouble Ahead

THE COMPLICATED topology of Lost Highway leads a man to double back into his past to warn--hopelessly--of trouble ahead. The central character of the first half is Fred Madison (Bill Pullman, doubling for Kyle MacLachlan), a sax player who may also be a nightclub owner.

Either way, he is very well off. There isn't anything in his apartment that didn't cost at least $1,000. The windows shut out as much natural light as possible, so he can sleep days.

It's a spacious blond-wood casket of a place. Even the VCR--which turns out to be the weak spot in the fortress--has a wooden cozy around it. The pink light from the electric torchiers doesn't warm the rooms, nor does light from a skylight penetrate them. There are dark shadows on the walls, shadows deep enough to swallow a man whole.

One of these shadows is Fred's wife, Renee (Patricia Arquette). When the two make love, she is so aloof that he turns flaccid. Renee is underneath Madison. The moment is held. Renee's breasts don't jiggle as he thrusts. They ooze, in slow motion, like the swell of waves under a skin of spilled oil.

When Madison has to break the session off, out of despair, his wife holds him with the slightest compassion imaginable. She is, we suspect, only a few days away from leaving her husband. Madison's situation is worsened by some anonymous videotapes that arrive in the mail, and by his meeting with the Mystery Man at a party.

The Mystery Man is a demon, I think. He may be Satan himself. He's played by a wizened Robert Blake with white face powder and shaved eyebrows. Blake has Bela Lugosi's own car-door ears and blood-red lipsticked mouth. It's a typical Lynch strategy to use a rotting child actor (such as Dean Stockwell in Blue Velvet) for the maximum in decadence.

Later, after his meeting with the Mystery Man, Madison literally disappears. The story changes, but the mood doesn't break. An auto mechanic with a criminal record, Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), ends up in a dangerous tryst with Alice Wakefield (Arquette again). The Mystery Man reappears to finish the story.

Photo by Suzanne Tenner

Rare Intensity

LYNCH WROTE Lost Highway with Berkeley writer Barry Gifford; the two also collaborated on 1990's Wild at Heart. Gifford, a fan of film noir, is apparently intimidated by Lynch's willingness to harrow the audience. Wild at Heart seemed to exist only to top Blue Velvet for shock value. Lost Highway is a calmer film. There is less skull-crunching, more mood, more velvety paranoia.

Even in the scene designed to most rile audiences--a forced strip by Arquette as Alice--there's an element of doubt. Alice may be a nice girl who is a victim of circumstance. She may be so marked by her humiliation that she hardens forever. Or really, she may kind of like the whole thing, because she is, well, bad.

After Alice tells her story of what the vicious gangster Mr. Eddy (Robert Loggia) made her do, and after Pete and Alice kill a man together, they make love in the desert in the light of the high beams of a parked car. Alice is overloaded with light; her platinum hair is so white it leaves shadows; her skin is so bleached-out her nipples are blazing.

She's rears up like a horse over Pete, who is moaning, "I want you, I want you." Alice grows stronger, as if the light were feeding her. At last, she answers his bleating "I want you, I want you" with a triumphant "YOU'LL. NEVER. HAVE. ME!" Is it Arquette as the vengeful Spirit of Pornography--the image of a woman completely exposed and yet completely unavailable?

Who knows for sure? Watching a Lynch film is like watching a virtuosic musician playing a one-of-a-kind instrument that only he knows how to play. He seems to be breaking free of narrative. The intense situations are unlinked to plotting and are brought to a boil through a sort of cinematic shorthand--the quickest route to an intensity rare even for Lynch.

Horror Without Consolation

I UNDERSTAND people who find his images repellent and his narratives weird. In an interview in Sight and Sound, Lynch laughed nervously over the synopsis of Lost Highway because it sounded like "baloney." (Was it The Return of Chandu in which Lugosi squelches a wise-ass who has just mocked some arcane ritual as "superstitious baloney"? "Superstitious, perhaps," Lugosi replies. "Baloney, perhaps not.")

Horror ought to transcend logic and ordinary reality. But Scream, the most popular horror movie in the last six months, is very logical in its way--a facile satire, modestly flattering to the horror-film audience it characterizes as rational people who can tell the difference between screen violence and real violence. Lynch is the last director left who is willing to present horror as horror, willing to baffle us, willing to wound us.

Twin Peaks became a sort of national joke, probably because of the supernatural elements; the use of demons in movies is automatically considered evidence of lightweightedness and incoherence. (Too bad the same can't be claimed of movies with angels. Wasn't Twin Peaks just the other side of Highway to Heaven?)

Lynch's sensibility held the show together. The various guest directors didn't have Lynch's personality, and they took Twin Peaks into tangents. (And the TV audience is happier when a show is more clearly joking, as in Northern Exposure and The X-Files.)

Lynch's movies don't make you feel mildly chilled or rational. He isn't a consoler. It's said that the real purpose of horror is to offer a stylized way to confront your fears. There's no confrontation here; instead, Lost Highway confirms your worst fears.

And that is true horror: the worst suspicions and fears of life made plain. To paraphrase Dashiell Hammett in The Maltese Falcon, when you watch a Lynch movie, it is as if someone had taken the lid off of life and let you look at the works.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

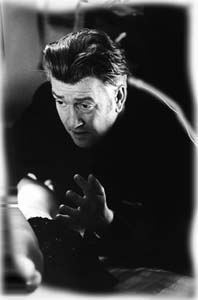

Suzanne Tenner

Garmonbozia Man: Lynch obsesses over the pain and suffering beneath the surface of our lives.

Lost Highway (R; 135 min.), directed by David Lynch, written by Lynch and Barry Gifford, photographed by Peter Deming and starring Bill Pullman, Patricia Arquette and Balthazar Getty.

From the February 27-March 5, 1997 issue of Metro

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.