![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Dusty in Memory

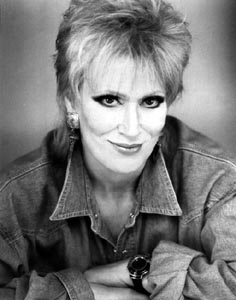

Preacher's Daughter: Dusty Springfield. Mike Owen

Dusty Springfield put flirtation in the air with her sixties hits A friend gave me the wrong information. The first time I heard the album Dusty in Memphis all the way through, he informed me that Dusty Springfield was a 17-year-old girl from the hollers who wandered into the famous Stax/Volt studio in Memphis and recorded the album after an on-the-spot audition. "Billy Ray was a preacher's son, and when his daddy would visit he'd come along." I should have recognized that line as English poetry from the phrasing, with the accent on "and" instead of "when." When Springfield sang, it sounded like A.E. Housman set to gospel. Mary O'Brien, who died March 2, was actually the last and most ethereal singer of the British invasion. She took the stage name Dusty Springfield in the early 1960s. Springfield was at the treacherous age of 29 when she recorded Dusty in Memphis in 1968. Previously, she had released several folk-rock albums in England with her group, the Springfields, and a hit single, the bland, semi-showtune "You Don't Have to Say You Love Me." When she couldn't get a follow-up hit, she moved to Memphis. There she recorded with the producers who would help reconstruct Elvis after years of clock punching in Hollywood. Dusty in Memphis (available on Rhino Records) is still one of the most remarkable albums of the 1960s. The production quality is a brilliant example how musical tension is created and relieved. Dusty's old/young voice is set beautifully, rightly, as it never was again. Her purring rasp is framed with exclamatory bursts of funky, nattering electric guitars and stinging gasps of gospel chorus. Exotic instruments sneak in on the periphery: tasty--and tasteful--sitars and oboes and Eastern European spy-music strings. The fully orchestrated background provokes Springfield from shy lady to a woman shouting in triumph. The scheme of Springfield's greatest hit goes back to the "floaters," those couplets that turn up in the verses of a hundred different folk and blues songs. Example: "I'm not the butcher/ I'm the butcher's son/ But I can chop your meat until the butcher comes." Probably every blues musician did that verse or some verse like it. In "Son of a Preacher Man," the boy Billy Ray has inherited his father's silver tongue and charisma, talking the girl clean out of her virginity. "Being good isn't easy, no matter how hard you try," Springfield says, matter of factly, in a voice that suggests that she wasn't trying all that hard. Windmills It's an oddity, but "The Windmills of Your Mind," that nutty Alan and Marilyn Bergman musical mixed metaphor, was another hit for Springfield. The song changed the flavor of the original version of The Thomas Crown Affair from an artsy heist picture into a nigh-Antonioni-style portrait of the idle rich. I prefer Astrid Gilberto's rendering of the tune--the quaintness of the lyrics are made pretty by Gilberto's sobbing, demotic English. But Springfield's version is still a remarkably bizarre song. "The Windmills of Your Mind" is too crazy to be anything but a piece of its crazy time, and it is almost airily psychotic: "Is the jingle in your pocket/Or is the jingle in your head?" A question like that made a lot of sense in 1968. Springfield's influence on the movies was limited but always intense. As in The Thomas Crown Affair, Springfield's music was best used on screen to describe the inner life of impassive criminals. Uma Thurman doesn't have to flirt with John Travolta in Pulp Fiction; all she has to do is turn on "Son of a Preacher Man" and the flirtation is in the air, piped into the room, as if it were central heating. In the maligned 1967 Bond film Casino Royale, the curious courtship of Evelyn Tremble (Peter Sellers) and Vesper Lynd (Ursula Andress) is seen through a huge aquarium, as the two slowly slide toward each other. On the soundtrack is "The Look of Love" by Springfield. Springfield's isolation-booth treatment of the vocals glazes the melody with frost. "The Look of Love" actually becomes more remote as the song goes on, as if Springfield were dissolving as she sang. Hear especially Springfield's near sing-song reading of the line "How long I have waited." Dionne Warwick, Springfield's contemporary and the woman who usually recorded Burt Bacharach/Hal David songs, would have made it known she wasn't waiting a minute longer. Springfield suggests that her wait would never be over. "The Look of Love" says everything, and yet it doesn't overpower the narrative. Springfield's song supplies longing and pain to the formal, artificial courtship of would-be spy and rich murderess. Don't Forget About Her Springfield had the bad luck to die the day before she was slated to go to Buckingham Palace and receive an Order of the British Empire. Her obituaries were bad luck too. Reuters printed an obit that was as close to vicious wit as an obituary gets. Quote: "After disappearing from the charts, Ms. Springfield let slip in a 1975 newspaper interview a veiled admission that she was bisexual. She later moved to Los Angeles." Conservative English people will know the correct way to read that sentence: "To punish herself for financial failure, she became a sexual degenerate. Springfield brought further shame upon herself by moving to Southern California." Obit language can't describe, say, the natural way Springfield went from a whisper to a scream on the unbelievably rousing "Don't Forget About Me," on Dusty in Memphis. And one can imagine what kind of suffering is tidied up by the nice daily-paper phrase "a five-year battle against breast cancer." I'll just conclude by noting that every time I've seen Pulp Fiction, an appreciative rustle goes through the audience when the syncopated drums and the first fresh, buttery guitar notes of "Son of a Preacher Man" rise up. No doubt, the song will still be cozying up men and women--or, hell, men and men, and women and women--long after we've all gone to join Dusty Springfield. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

Web extra to the March 4-10, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.