Defective Story

The Coen brothers bowl a strike

FILM NOIR WENT FROM ripeness to rot decades ago. Filmmakers obsessed with those beautiful artifacts of postwar malaise have only a few options in the late '90s: either comment on the rot (as in Twilight) or try to copy the mood while tipping an audience the wink (as in Palmetto). Or they can do what the brothers Ethan and Joel Coen have done in The Big Lebowski: strip the structure down to its bones and construct an ersatz-heroic monument on top of them.

In the opening scenes, we see views of a lonesome tumbleweed rolling around the streets of L.A. Soon the film zeroes in on a human tumbleweed: "The Dude" (Jeff Bridges). Who is the Dude? Even the Stranger, the cowpoke narrator (Sam Elliott) who opens and closes this film, has to grope for words, but he tries: The Dude is history embodied, the right man in the right place.

The Dude is the laziest man in L.A., and that makes him a contender for laziest man in the world. He's distinguished, really. The Dude--a shaggy beat in bathrobe and Bermuda shorts--is a mariner in a sea of white Russians, a serious, hard-drinking bowler. He's Cheech and Chong rolled into one.

But the Dude has a birth name, Lebowski. And a case of mistaken identity sucks this passive hero into the Philip Marlowe role in a pure Raymond Chandler plot: there's a kidnapping; a femme fatale; a wheelchair-bound millionaire (David Huddleston) with a nympho wife (Tara Reid); and a variety of eccentric troublemakers. The best suspects for the kidnappers are members of a Kraftwerk-like German techno-band of self-professed "nihilists."

Nihilists are worse than Nazis even, claims the Dude's rageball bowling buddy, Walter Sobchak (John Goodman updating the William Bendix part from The Blue Dahlia). "At least Nazism is an ethos."

Director/writer Joel and producer/writer Ethan Coen do to an old movie plot what bands like the Residents and Negativland do to a pop song. The same structure is there, but the artists change emphasis, turn up the volume or solo with an out-of-context instrument to turn the familiar music into something freakish.

Chandler's Marlowe was cool and unruffled, a few drinks ahead of everyone else. The Dude's nigh-total inertia is, on the other hand, his own kind of saintliness. Down these mean streets a man goes because he's too drunk to tell how mean they are. Chandler's own haphazard way with plots is at last matched with a really haphazard hero. "This case--uh--it has lots of ins, lots of outs, lots of whatevers," the Dude explains hopelessly. Inaction is the Dude's best defense and best offense.

He needs his calm when he is assailed by the usual menaces of a noir: gunmen who barge in out of nowhere; the bad girl who proves how bad she is in a hot second; the psychedelic knockout drugs. Ben Gazzara, as a porn tycoon, is so sinister in the ancient "Can I freshen that drink up for you?" bit that we see the Mickey Finn-laden cocktail arriving from a mile away.

But how are we supposed to anticipate a bowling-themed Busby Berkeley routine in the dream sequence after Lebowski keels over from the drugged booze? Not since the Firesign Theater's Nick Danger series has there been such a ridiculously warped detective story.

IT'S A MOVIE ABOUT MOVIES, a Beat the Devil for our time. Unfortunately, The Big Lebowski completely lacks an ending, as if the Dude himself had scripted it. All the time spent filleting red herrings robs the audience of the customary satisfaction of seeing the story tied up in a improbably neat little bundle.

What, for instance, happens to the weird artist Maude Lebowski? Julianne Moore, with a divine fake Katharine Hepburn accent, plays a feminist artist in a time warp. She describes her art in a spoken womanifesto, the likes of which hasn't been heard since 1975. Since she's so well-spoken, we're convinced that she's the only one in the movie smart enough to have concocted the kidnapping, but she makes only a few appearances and then drops out of sight.

The Dude's nemesis on the bowling lanes is the mincing ex-child molester named Jesus (John Turturro), who is so extreme that he even blows a kiss to the perplexed, llama-eyed Donny (Steve Buscemi), a member of the Dude's bowling team. A lifetime of watching B-movies urges us to think that Jesus has to be in on the kidnapping, but the movie drops him, too, like a bowling ball.

The lack of a good ending is especially frustrating because the Coen brothers usually throw such a mean curve. The finale of their antic, cartoonish Raising Arizona is astonishingly sad. That ending, in which the future of a probably doomed couple is previewed in a series of seriocomic snippets, is the best pastiche of short-story writer Raymond Carver's mood ever seen in the movies.

Fargo also has an emotionally powerful ending. Frances McDormand's pregnant copper is hauling the murderer (Peter Stormare) to jail, insisting to him that the world is too beautiful for greed, when all we can see is a whiteout: white skies and snowbound land. Some people think that Fargo is a patronizing dialect comedy, but I think in those moments, McDormand's Marge Gunderson displays the Paul Bunyan-sized moral strength inside of her.

In The Big Lebowski, the Coens try their usual talent for sucker-punching the audience with a misguided funeral scene at the end. The scene--two men disposing of some human ashes from a cliff over the beach at Santa Monica--is mistimed, too deliberately sentimental, just as the ending of Raising Arizona would have been without its surreal artifice.

The Big Lebowski is set right before the Persian Gulf war. The last bits of ambient Reaganism on screen make the Dude's desire to sleepwalk through life credible. It's the same trick as seen in Animal House, where the characters had only a choice of being uptight bores or drunk wastrels.

The film makes the straight world look like a place you wouldn't want to visit, and it doesn't need to explain why the Dude and Walter love each other under all of the squabbling. We don't need to see them hugging to understand how the scorn of the outside world keeps them together as friends.

IT ALL SOUNDS AS underpowered as a one-shot sketch: Charles Bukowski, Private Eye. Still, The Big Lebowski is a peculiarly magic comedy, easier to applaud and easier to recommend than anything else that's yet come out in 1998. As is often the case in the Coen brothers' movies, there's tartness underneath the anarchic wit, a sense of bruised feelings beneath the mockery.

In one bitter but funny scene set at a coffee shop, Walter chases the Dude away with his raving. The waitress tries to shush Walter, but he's making his point. He has free speech; he has his rights: "I'm going to sit here and enjoy my coffee." The camera stays on Walter, as the waitress and customers scowl at him; he drinks his coffee defiantly, another fool who thinks he's drawn a line in the sand.

By the end, I was wishing that there'd be a few more Jeff Lebowski anti-adventures. One or two more, anyway--no need to overdo things. Bridges is almost 50, but he has a kid's cheerfulness and unself-consciousness here; his mighty deadbeat is a delightful characterization.

Lying on the floor, listening with headphones to a rumbling, crashing audiotape of a bowling tournament, the Dude is such an oasis of such calm that he seems destined for a happy rebirth as someone's beloved house cat.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

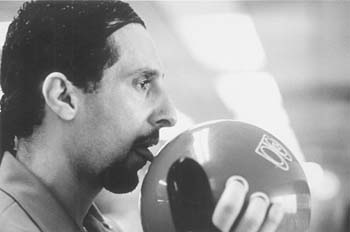

Life in the Slow Lane: John Turturro in 'The Big Lebowski.'

The Big Lebowski (R; 100 min.), directed by Joel Coen, written by Joel and Ethan Coen, photographed by Roger Deakins and starring Jeff Bridges.

From the March 5-11, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)