![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

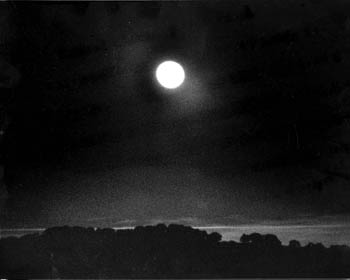

Photograph by Christopher Revell Mecca Difference: The U.S.Muslim community has vacillated between using Saudi Arabian announcements and local moon sightings to choose the date for the sacred Muslim holiday Eid al-Adha, which, as a result of the disagreement, ended up on both Feb. 11 and Feb. 12 this year. Dark Side of the Moon How confusing is it to figure out when a new moon is sighted? For Muslims all over the world trying to nail the date of this year's Eid al-Adha, it was a contentious--and some believe political--matter, indeed. And it's not over yet. By Najeeb Hasan

They question you [O Muhammad] about the crescents. Say: "They are seasons fixed for mankind and for Pilgrimage. Qur'an 2:189 [English rendition by the Nawawi Foundation] Two weeks ago, when Tahir Anwar, the imam of San Jose's downtown mosque on Third Street, just about a two-minute stroll north from St. James Park, returned home after almost three weeks on the Arabian peninsula, it was a bit difficult for him to swing right back into his daily routine, and jet lag wasn't the only factor. The imam had just performed the hajj, for most Muslims not only a cleansing but also the ultimate confirmation of religion before death itself. The word hajj, in fact, is linguistically related to the word hujah, which is translated as "proof," teaches a Bay area scholar. And so, visiting the Kaaba--the empty black cube (once full of idols, now cleansed) in the center of Mecca that Muslims believe Abraham built--confirms, by its very emptiness, the impossibility of conceptualizing the divine, the incapability of the finite to capture the infinite. Meanwhile, many of Imam Tahir's own confirmations came, like so many pilgrims before him, through the swarming masses of humanity surrounding him. "The greatest sight is the people." The imam shakes his head in disbelief of the memory. "What's more amazing is the different countries that people come from--Indonesia, Thailand, Bosnia. ... When you're walking between groups of people, it's like you're walking from one country to another in a matter of minutes." It's this social egalitarianism, this unity, that Muslims pride themselves on. It was, of course, an awed Malcolm X who wrote home about sitting sincerely with "fellow Muslims, whose eyes were the bluest of blue, whose hair was the blondest of blond and whose skin was the whitest of white." But while unity overwhelms in the sanctuary of Mecca, back in the United States, the second and final holiday season of the Islamic calendar has, again, brought with it a jurisprudential tiff that Muslims still can't seem to resolve. The celebration of Eid al-Adha, the holiday that honors Abraham being asked to sacrifice his son and then being restrained by God, falls during the hajj season, but Muslims are (still) having a nasty time figuring out exactly when it should be. For example, the downtown mosque, while Imam Tahir was away, celebrated Eid beginning on Wednesday, Feb. 12 (Imam Tahir's younger brother led the Eid prayers at the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds). On the other hand, the largest mosque in the South Bay, Santa Clara's Muslim Community Association, celebrated its Eid the day before, on Tuesday, Feb. 11. On a national level, the Muslim organization with the biggest clout, the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), also declared Eid to be on Feb. 11. On an international level, Saudi Arabia, where Imam Tahir was during Eid, announced it to be on the 11th, while most other predominantly Muslim countries declared the holiday to be on the 12th. Ask ordinary Muslims what this disagreement is all about, and they'll likely shrug it off not as a disagreement but as a "difference of opinion." Ask conspiracy theorists, and they might spout off something about Sheik George W. and the United States exerting political pressure to evacuate the pilgrims from the Middle East early to gain time in their plans for invading Iraq. From the Christian perspective, it's rather like not being able to come to a consensus on when Christmas should be (although, because of the accepted ambiguity of the Islamic lunar calendar, not exactly). But, perhaps more interesting than the problem itself are the spiritual implications inherent to the disagreement. Moon Matters The crux of the difficulty lies in the sighting of the new moon, which marks the beginning of the 12th Islamic lunar month, Dhul-Hijjah. To determine the beginnings of their months, Muslims have traditionally sighted the new crescent moon. Because the moon's orbit around the Earth is a little more than 29 days, Islamic months are either 29 or 30 days long. If there is doubt or no sighting because of cloudy or other atmospheric conditions, then it is agreed upon by Muslim scholars that the new month begin 30 days after the beginning of the previous month. Simply put, it is accepted by Muslim scholars that Eid al-Adha, instituted in the first year of the Islamic calendar, begins 10 days after the sighting of the new crescent moon of Dhul-Hijjah. The hajj, established in the sixth year; can be said to fall on the ninth day of Dhul-Hijjah, when the pilgrims are required to convene on 'Arafa. And while scholars say there is a conceivable legal argument to be made for relying on another community's moon sighting or announcement of Dhul-Hijjah, they also say that when distances are vast, as is the case with the United States and Saudi Arabia, the general consensus has been to rely on a local moon sighting. The disagreement in the United States occurs because ISNA, in the name of unity, took the jurisprudentially unusual step of relying on Saudi Arabia's announcement of Dhul-Hijjah and not on local moon sightings in North America, which it paradoxically relies on to determine the start and finish of the other Muslim holiday, Eid al-Fitr, that follows the holy month of Ramadan. What exasperates knowledgeable onlookers more is that ISNA has wavered back and forth on the issue: first, it followed Saudi's lead; in 2001, then-ISNA-President Muzammil Siddiqi conceded that ISNA had no legal support for its stance and reverted to traditionally accepted local moon sightings; and now, it's abruptly back with the Saudi announcement. Moon Man Enter the man of the moon, Khalid Shaukat. A consultant to ISNA, the Washington, D.C.-based scientist and computational astronomer is well known for his work in helping establish prayer direction for mosques and making lunar calendars and prayer schedules and, of course, for his moon sightings. Shaukat also keeps up a website, www.moonsighting.com, that collects moon-sighting reports from all over the planet. Shaukat, who says he was not consulted by ISNA in its most recent decision to follow the Saudi announcement of Dhul-Hijjah, has been tracking official Saudi lunar calendar announcements for the last several years and has his own theory about why the Saudi lunar calendar differs from the moon sightings of the rest of the world. If it's true, ISNA could be in even more jurisprudential murkiness. The Saudis, Shaukat believes, have a precalculated lunar calendar that's based on the actual new moon, as opposed to the sightable new moon. When the actual new moon occurs, both the orbits of the Earth around the sun and the moon around the Earth correspond, and the sun, the moon and the Earth line up together. Because no light from the sun falling on the moon can reach the Earth, the actual new moon, which can occur at any hour of the day, is invisible, making things rather difficult for traditional Muslim moon sighters. And so Muslims still base their calendar on the crescent moon. Despite the scientific inaccuracy of a calendar based on a sightable moon (compared to the Gregorian calendar. or even one based on a computationally determined actual new-moon calendar), Muslims say there's a hikma, or wisdom, in their calendar--a wisdom that the Utne Reader implicitly recognized two months ago with a cover feature that was essentially about human enslavement by artificially structured time. Relying on the moon, Muslims further contend, allows everybody to relate to time--from Balochi nomads to Western-educated professionals. Not everybody can relate to computation-dependent concepts of time. Shaukat's theory continues that when the 29th day of the month arrives, for formality's sake (or under religious pressure), the Saudis are willing to accept any moon-sighting report to confirm their precalculated calendar. Because the actual new moon is invisible, they never see the moon on that day, but sometimes they mistake another object in the sky for the moon, and the authorities call the month on the 29th day. If not, the month is called the next day. "Their calendar is accurate--with minor modifications--if you consider the actual new moon as the beginning of the month," Shaukat says. For this year's Eid al-Adha, Shaukat's website reported that on Feb. 1, the day of the Saudi announcement of Dhul-Hijjah and the day that ISNA based its Eid on, the moon was 14 hours old and not visible on any continent in the world (only some Polynesian islands had the astronomical ability to sight the moon). On Feb. 2, moon-sighting reports came in from countries from Pakistan to the United States (a span that includes Saudi Arabia), making Eid, according to Shaukat's understanding, 10 days later, on Feb. 12. Before this year's Eid and hajj, one Muslim scholar remarked that if you really want to find Muslims who know their deen (religion) then go to 'Arafa the day after the rest of the pilgrims leave--the most learned ones will have stolen back to 'Arafa to fulfill their requirement of being there on the ninth day of Dhul-Hijjah. By an Eyelash San Jose resident Youssef Ismail's eyes sparkle when he talks about the crescent moon. "Sometimes it's as thin as an eyelash," he says excitedly, extending a forefinger with an eyelash resting on top. A mechanical engineer at Stanford and a nature photographer, Ismail--mid-30s, slender and spry, with a full beard and a face that shines beneath it--has been looking for the new crescent every month for the past 11 years. His search started as a graduate student at Stanford, when the Muslim Student Association was, typically, arguing about when the month of fasting, Ramadan, should end. "Finally, I asked a question," he recalls. "'Does anybody ever go out and look for the new moon?' Everybody looked at each other and said, 'No.' Then I said, 'What are you arguing about then?'" And so, the divine hikma that Ismail discovered 11 years ago remains unseen by champions of both sides of the debate: that there are spiritual implications in dismissing the ambiguity of traditional knowledge, the understanding that you have to actually sight the moon, to connect to the heavens. In a sense, what has gone unnoticed is the mere fact that delegating moon sighting to higher authorities has symbolically wrenched away the Muslim's right to be part of creation. Ismail, satisfied with his own certainty in sighting the moon, steers clear of the ISNA-Saudi debate. For him, it's not an issue; his own certainty is the issue. "I think that connection [with creation] is a very important aspect that Muslims are missing today," Ismail says. "[To not sight the moon] is removing us from creation. Now, whether that's right or not, I don't know. But God tells us in the Qur'an to reflect on his signs. You can't do that if you're not going out and actually becoming part of creation. We are part of creation, but through our science and technology we have alienated ourselves from what creation is."

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the March 6-12, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.