![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

City of Masks

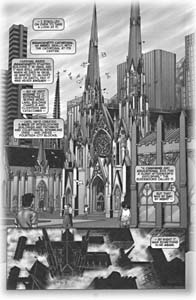

Church of Chills: In Kurt Busiek's imaginary metropolis of superheroes, the evil Confessor takes up residence in a Gaudiesque cathedral--"never finished, never consecrated, fallen into disrepair."

The skies of Kurt Busiek's Astro City are overrun with caped crusaders AS CAN BE seen in the new issue of Astro City (Homage Comics; $2.95), a sense of place can be quickly established with just a few details. Astro City, the superhero-ridden metropolis that Kurt Busiek chronicles in the continuing series, comes complete with neighborhoods, landmarks and city secrets. (One tantalizing mystery: a statue of a warrior captioned "To Our Eternal Shame"). Busiek is one of the more vivid writers of superhero comics today. Even in a hackneyed genre, he avoids writing himself into a corner of his imaginary city of the present (which might be, except or a few details, Vancouver, British Columbia). By keeping everything low-key, Busiek makes his premise of a town famed for its plethora of flying costumed men and women relatively believable. His heroes are drawn in the template of the familiar figures from DC and Marvel: a Superman-like Samaritan and a character called Rex who has bricked skin like Ben "The Thing" Grimm of The Fantastic Four. And as in the Marvel comics of the 1960s, the populace is used to seeing superheroes; it's a matter of comment when they show up, but it's not usually a matter of awe. The crowded skies promise Busiek more freedom than the average comic-book creator enjoys, and it's easy to see some of the threads Busiek might take. Astra, the daughter lost in the shuffle of the First Family (a mutant superhero group modeled on the Fantastic Four) in Astro City #1, comes into her own in the second issue. I suspect she's probably going to become friends with the two little girls from the first episode, who have just relocated from Massachusetts. Their father is used to the idea of superheroes, anyway, having bumped into a few of the breed in Boston ("I saw the Silversmith a couple times. I saw the Brahmin once, too, out in Saugus").

An Astro City fan page.

ISSUE #4 is so much like a gay coming-out story that it's practically The Rubyfruit Jungle. Kinney, a small-town boy alone in the world, comes to Astro City. He's heard of a bar called Bruiser's where superheroes go, and he gets a job there as a busboy. A kindly bartender tips him off that he's too good for the rough trade. If he wants to meet a better breed of superheroes, he should apply to work at Butler's, a private club where the clientele is well dressed and well behaved. At Butler's, Kinney finds what he's looking for, a respected patron, an older man to initiate him into all of the rites of superherohood. I felt like I was reading a 1950s novel about gay life by James Purdy or Truman Capote; the story seemed to be taking place between the lines. No doubt this response comes from having lived too long in the part of the country where an all-male bar means but one thing. The most recent issue, Astro City #5, continues the story of Kinney with a different theme. Kinney's new identity is Altar Boy (lapsed Catholics will be sniggering now, I know), apprenticed to the successful vigilante he met at Butler's, the Confessor. This hooded character looks like the priest whose confessional booth you'd avoid if you didn't want to end up being given a penance of 1,000 Hail Marys. The Confessor makes his headquarters in a Gaudiesque cathedral that's swallowed up 14 city blocks--"never finished, never consecrated, fallen into disrepair." Most of Busiek's heroes are modeled heavily on other comic characters, and for broodiness and goth appeal, this Confesser is obviously meant to be the Batman of Astro City. Cult murders are being committed on the edge of town, and a proselytizing group of evangelistic Christian superheroes called the Crossbreed--referred to by the impious as "Jesus freaks"--have just arrived on the scene. All of which points to a brewing theological struggle in future issues. It should make for diverting reading in the short run. Busiek's challenge in the long run, having set up the plot, is to reconcile the two halves of the city: the sparkling good neighborhoods and the bad parts of town around the cathedral and Bruiser's bar. Vigilantes don't have much work to occupy them in well-run burgs, and the better pulp takes place in cities where everything is on the fritz. Busiek and his studio have so far been good in setting up a sense of place in Astro City. Is it too much to hope for that Busiek will write about how, as in real life, the splendor of one half of the city contributes to the squalor of the other? [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.