![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

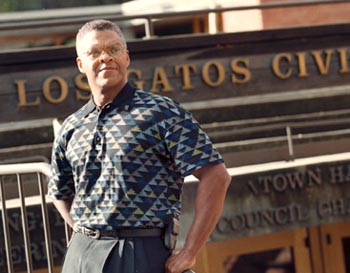

Photograph by George Sakkestad Businessman Tommy Fulcher: 'The first thing I taught [my sons] is that you're always respectful to cops. ... [F]ollow their instructions. Don't make sudden moves.' Color Separations Actor Danny Glover's experience in unsuccessfully trying to hail a cab in New York is not unique. Even for African Americans who have 'made it' in Silicon Valley, vestiges of racism remain, in ways many perpetrators don't even realize. By J. Douglas Allen-Taylor A FEW WEEKS AGO, I was in line at a popular South Bay electronics store. A distinguished-looking African American man was at one of the counters with a woman I presumed was his wife, buying several computer accessories. The man was bald and very dark, looked to be in his 50s, was dressed casually and talked as if he'd had a good deal of education. When this customer handed the clerk a credit card, the clerk asked him for a picture identification. The customer said nothing at first, but after the transaction was over and the clerk was putting the sales items in a bag, he asked the clerk, "Why did you ask me for identification?" The clerk looked up and gave a small smile and said, "It's store policy, sir." The customer looked puzzled. There was a white customer at the next counter, and the African American man turned and asked him if he'd made his purchase with a credit card. When the white customer said "yes," the black man asked him if he'd been asked to show a picture I.D. The white customer shook his head. The African American man turned back to the clerk and asked, "Why didn't he get asked for I.D.?" The clerk's smile got a bit smaller. "I don't know, sir. I just know what they tell me to do." I told a friend about the incident, a white reporter whose opinion I value, and he told me he thought I was overblowing it. "How do you know the other clerk wasn't supposed to get I.D., and he just screwed up?" But he'd missed the point, hadn't he? The point was, almost every living African American has been the victim of racism and discrimination or has heard the tales from close friends or relatives. And so we never know whether a breech in "store policy" is merely an oversight or has some deeper meaning. We all have our stories. I once got stopped by a police officer late at night in the airport parking lot in Charleston, S.C., while I was lifting a battery out of a car. He made me drop the battery, pushed me up against the hood and had me spread, patted me down for weapons. When he was satisfied that I was clean, he asked me what I was doing. "Trying to take my battery down to the gas station and get it charged," I told him. "I just flew in from Atlanta, and my car wouldn't start." After a check of my papers showed that, indeed, I was the owner of the car, he didn't miss a beat. "Well, if someone was out here boosting your battery," he said, "you'd be glad I stopped them." To this day, I suppose, he probably doesn't understand why this got me more pissed than the original shakedown. When I was growing up in the East Bay in the 1950s, San Leandro was known as a town unfriendly to blacks. Child or adult, it didn't matter. Police, store clerks, restaurant waitresses all let it be known in subtle and less-than-subtle ways that our presence was not desired. I remember riding up East 14th Street on a bicycle with some friends, being stopped in downtown San Leandro by a police officer and asked, "What are you boys doing here?" He made it plain that he was not pleased with our presence, and we turned around and rode back to the Oakland border. Such incidents never leave your mind, no matter how deep you try to bury them, no matter how much you try to structure your life as if they did not exist. It is the brooding, lingering residue of slavery, the system that taught African Americans to doubt our self worth, to think that we are less deserving than white people. A hundred and thirty-five years after Emancipation is not long enough to erase 300 years of social conditioning. And so, when a white customer goes into a restaurant and fails to get served, he generally just chalks that up to sorry service. Faced with the same situation, a black patron always wonders, "Is it because I'm black?" The question nags and never goes away. Celebrity status is no buffer. Actor Danny Glover, one of the most recognizable people in America, found himself publicly embarrassed late last year when he and his daughter could not get a taxi to stop for them in midtown Manhattan. The cab drivers apparently did not want to pick up a large black man. Some years ago, Hall of Fame baseball star Joe Morgan was arrested at the Los Angeles airport because he fit the profile of a drug dealer. The profile? A black drug dealer who had been arrested earlier told police that his accomplice "looks like me."

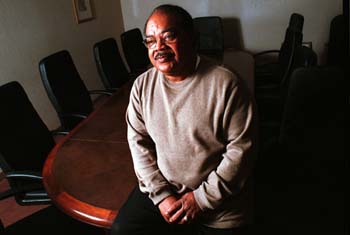

Los Gatos Councilman Jan Hutchins: 'I've tried all my life to transcend what I believe are the stupidities of our racial differences.' Some African Americans deal with the problem by attempting to ignore it and not letting it intrude on their lives. "I've tried all my life to transcend what I believe are the stupidities of our racial differences," says Los Gatos City Councilman Jan Hutchins. At various times, he has served as mayor of Los Gatos and as a highly visible anchorman on several Bay Area television stations. "My friend and I were talking about how I had the perfect, bucolic, small-town childhood back in Ohio. And he said, 'But it was a really racist town and people gave you a really hard time, and the girls wouldn't date you just because you were black.' And I went, 'Yeah, but I liked it. It was OK to me. Just because they're stupid, I can't do anything about that.' And so I miss a lot of what other people might see. I'm not looking for trouble. I look for people to like me and to get along with me, and so that's kind of what I find and see. And, in fact, my so-called celebrity has benefited me in many situations. I know it has." Asked if he thought that people might be stereotyping him by race and, because he's the type of person he is, he might be overlooking them, Hutchins replied, "Totally. Totally." He's totally right. A Metro staffer describes an incident some three years ago at the Los Gatos Coffee Roasting Company, which is owned by Hutchins' wife. The Metro employee was seated inside at a table next to a white couple, when they observed Hutchins through the window talking to someone outside the restaurant. The woman inside scratched her head and said to her male friend, "Who is that fellow? I've seen him somewhere before?" Her companion replied, in the best Amos-and-Andy accent he could muster, "Oh, you don't know who that be? That be Chaka Khan." Other African Americans find themselves confronted with the problem even when they are not going out of their way to look for it. Ward Connerly is by no means a race crusader. The Sacramento businessman and University of California trustee is best known for his active sponsorship and support of Proposition 209, the controversial state initiative that banned affirmative action in public hiring and education. Connerly talks a little angrily about an incident in Washington, D.C., last year similar to Glover's. He came out of a movie a little after midnight and stood in line at a traffic circle to try to get a cab. "Most of the people in line were black, and a lot of them were families," Connerly says. "I had on a suit, tie, and dressed as I normally am. I noticed that the cabs were circling and some of them were not stopping, they'd simply go around the circle and come back again. They weren't passing up families. They weren't passing up individuals who were white. But they were passing up individual black males. I honestly do not wear race as an antenna. I'm not one of those who is constantly seeing things. And so I really wasn't very sensitive to race being a factor at all. So I just stood there patiently and finally worked my way to the front, and I was at the front of the line and a cab drove up. I got to the front of the line, cab pulls up to let somebody out, I walk over, put my hand on the back door to get in, he pulls away. So I backed up quickly, and then the next cab pulls around, and the guy stopped and I got in. I said, 'What the hell's going on here, with cabs pulling up and then pulling away?' This was a guy who was a black man from Ethiopia or from someplace, and he said, 'It's your color.' And I said, 'What do you mean, it's my color? They're black.' Meaning the cab drivers. He said, 'Yeah, but they're afraid.' And that was a rude awakening for me. I'd heard about this problem a little bit, but I'd never faced it personally." A year after the incident took place, Connerly is still upset by it. "The impression that I am somehow a criminal because of the color of my skin is not one that I am content to allow anyone to embrace," he says, "no matter what the statistics might suggest." But Connerly also says that the history of anti-black feeling in this country can cause an African American to see racial discrimination even in instances where none exists. "I was at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco a couple of years ago to serve as the master of ceremonies of the California Building Industry Hall of Fame," he says. "As I was getting off the elevator, two elderly white guys walked up and one of them says, 'Are you the man with the keys to open the room?' And I walked down the aisle a little bit more and that bothered me. So I doubled back and I asked the guy, 'What made you think I would be the one to have the keys to open the room?' He said, 'Well, sir, you were dressed in a blue blazer and gray slacks, and you didn't have any bags, so I just assumed that you were an employee of the hotel.' And I apologized and we shook hands. But instantly, instantly, my thought was that they were presuming that I couldn't possibly be a guest of that hotel because of my skin color. In that instance, I was the one who was looking for something that I later came to believe didn't exist. I was looking for it. I honestly think that there is a little bit of both that goes on. That some people, when you've been conditioned all your life to believe that there is racism and discrimination there, I think there is the tendency to suspect it sometimes when it may not exist. But that isn't to say that it isn't valid, that it doesn't happen, because it does." But Connerly feels that it is better to call attention to perceived discrimination, even if it is mistaken. "Whenever stereotyping and discrimination are there, it's not good for anybody, and somebody ought to call attention to it. In this instance, we're better off as a nation for there to be an overreaction to this kind of problem than for us to remain silent when the incidents are fewer than we think." Metro spoke with eight successful South Bay African Americans about their experience with discrimination and racial stereotyping in the valley. Their replies may be startling to many people who think that money, fame, power or education is enough to enable African Americans to transcend the old shackles of race in our communities.

Gary Heit

ONE TIME I WAS walking along at the hospital, I've got my lab coat on, the usual hospital scrubs, white coat and scrubs. The only people around here who wear white coats and scrubs are the doctors and the residents. Housekeeping has a very different kind of uniform. I'm walking along and hear this voice that says, "Excuse me." And I turn around, and there's this elderly Caucasian woman in her bed, and she goes, "Could you empty the trash?" I thought about it, and part of me was going, "Yeah, right," but I thought maybe she's confused, so I went and emptied her trash. I'm not above that. And later one of the nurses went in and asked her, "Why was the neurosurgeon emptying your trash?" Another time, I was walking up the stairwell at Stanford Medical Center, and I had on a scrub cap, my lab coats, stethoscope, booties on. Clearly, I was a surgeon on my way to the OR. There was a maintenance guy, a white maintenance guy, and he was changing the fluorescent light in the stairwell, and he looks at me, and as far as I can tell he was perfectly serious, and he says, "Oh, I'll be done here in a bit; you can clean up after." A couple of times a year, I'll walk into a room and introduce myself and say, "I'm Gary Heit, I'm the attending physician," and someone will go, "When is the doctor going to be here?" Or, I'll be there and be introduced as the attending physician, yet they'll turn to a white senior resident to talk to them. It's subtle stuff, but I'm learning to roll with it.

Superior Court Judge Ladoris Cordell: 'It got to the point where I just dreaded to go make inquiries for homes. It was awful, just awful. That was a shock to me because I was in Palo Alto.'

LaDoris Cordell

I DON'T OFTEN GO TO department stores, and that is in large part because it wasn't that many years ago when I would go to department stores and was followed, and it was obvious, and I got sick of it. So, yes, that's part of my life. When I was looking for a home to buy in Palo Alto, this was about 10 years ago, I became very frustrated because the racism was just so blatant. I remember one instance I went to a home where a "For Sale" sign was up and the person who answered the door was either a manager and/or a tenant there, and I was told, immediately, that there was nothing available. And, of course, I checked, and it actually was available, and I went right back and confronted her. During that same period, I went to one house where I was followed by the Realtor. She followed me everywhere, upstairs and downstairs. It was an open house, and there were a lot of other people there. The Realtor inquired what I was doing there and told me that this house was not for rent, it was for sale. The assumption was that I could not have been interested in buying a house. It got to the point where I just dreaded to go make inquiries for homes. It was awful, just awful. That was a shock to me because I was in Palo Alto, and I'm thinking, "This is a somewhat enlightened city."

Steve Pinkston

LAST YEAR MY WIFE AND I were down at a car dealership looking at some Volvos. We already owned a Volvo. Two of the salesmen there were bickering over who was going to be serving us. This was not because they were anxious to serve us. They've got a rotating ball which signals who's in line to serve the next customer. These guys were just arguing, "No, it's not my turn. It's your turn." They went back and forth. Finally, I just blew up. I said, "Look, are you prejudging me because I'm a black man, and you guys don't want to serve me? What's the deal here?" And then they quickly became apologetic. But I knew what was going on. I felt there was a prejudgment that here's a black man, he's not going to buy anything, so why waste their time? I've bought from this dealership before, but never again. Several years ago, a white student was behind Bellarmine shooting a paint pellet gun at some concrete pillars near the Caltrain line. A Caltrain worker on the train saw the student and called ahead to the San Jose police. The SJPD officer didn't get the location correct and went to the wrong stop. There were about 30 students waiting there to catch the train. Most were white, with a few Asians and one African American. The police officer made only one student get face down on the ground. Only one student was searched. Only one student was brought to the dean's office at Bellarmine. I was the dean of students at the time. The officer called my office before he brought the student over, and over the phone he told me, "Dean Pinkston, I have a student I want to bring to your office. He doesn't reflect the color of a typical Bellarmine student." Oh, what a shocked expression the officer had on his face when he came into my office. I later asked the other students who'd been at the train stop why the African American student was the only one to be searched. Not a single student gave a reason other than his color. This African American student went on to receive honors at Bellarmine and earned a degree from Gonzaga University.

SJCC Professor Merylee Shelton: 'Many of the white faculty members [at Sunnyvale High School in the '70s] would get up when I came into the faculty lounge and would not eat with me.'

Merylee Shelton

SOME YEARS AGO, I took a job as speech drama instructor at Sunnyvale High School in the Fremont Union High School District. This was in the '70s. Sunnyvale High no longer exists. It was a situation where I think the district was trying to establish some diversity among faculty at Sunnyvale. From what I understood, there was one Latin instructor who was black, and there were no other black staff members. They had hired a black young lady as the drama instructor at the beginning of the academic year. The faculty and students gave her such a rough time that, from what I understand, she had a mental breakdown, and so just after the Thanksgiving break, I came on. A high school drama instructor is usually required to do one major production during the course of the year in conjunction with the music and athletic departments. The music department wouldn't participate. And when I actually did have one meeting with the athletic department, I came late, and when I arrived the coach said, "Aren't you an Aunt Jemima?" And I said, "Excuse me, I don't understand what you're talking about." And he said, "Aunt Jemima's slow, and you're really slow." And I said, "If this is supposed to be funny, it's extremely not funny and I assume you're apologizing." And he didn't. Many of the white faculty members would get up when I came into the faculty lounge and would not eat with me. But that only was an experience that lasted for a couple of weeks, maybe. At some early point in time, I realized that it was not a good idea to go to the faculty lounge. It got worse. When I would do a drama production, I'd have students build sets and then I'd go home, and during the weekends and at night, someone with keys would come in and destroy the sets. I'm not saying it was faculty, but it had to be staff.

San Jose Councilwoman Alice Woody: ' You go shopping. You go into a retail establishment to shop, you are followed. ... Other people can walk in a store, browse, etc., but they're not followed around.'

Alice Woody

THESE TYPES OF THINGS happen on a daily basis. You go shopping. You go into a retail establishment to shop, you are followed. And my thing is, other people can walk in a store, browse, etc., but they're not followed around the way African Americans are. I've had numerous incidents of being followed in stores, in San Jose. The only thing that's different these days is that people aren't as blatant as they used to be. It's just subtle. When you go into a store, either they're following you around or you want help and you can't get it. But you let somebody else walk in after you, and they are very friendly and can go up and try and help that person. I was talking to one of my assistants about incidents where you go into a store and you've got to get change back, and you stick your hand out to get the change, and they put it on the counter. I have four children. They're grown and pretty much out of here. My children sense when someone is treating them differently, because they make comments, like, "Well, I guess sometime we'll get waited on." They are impacted by it. I think one of the reasons why my three daughters live on the East Coast and not here is that they say, "I'd prefer somebody just letting me know right off that I'm not welcome, instead of coming here and you think you are and you're not." It's had an impact. The fact that our children are made to feel inferior, so you're battling constantly to make sure they understand that they are important, that they're no less because they're African American. As a parent, you're constantly reinforcing their worthiness. Here recently, I was getting on the elevator here at City Hall, and there were people, and there was another councilperson, and there was me, and it was like this other councilperson, they were making room for her and doing this that and the other, and this person had to turn around and say, "This is Councilmember Woody." And at that point you could see the change in the body language. Until that person had said that, I was at the back of this crowd and they were trying to move and do things for the white councilperson.

Tommy Fulcher

I HAVE THREE SONS. My oldest is about 32, my middle is about 28, and my youngest son is 17. I was kind of raised on the streets, so I learned how to function on the street, especially with dealing with official power. As soon as my sons reached the age where they had to start going outside, even if it was just walking to the store, I started educating them on what they had to do to survive on the street. The first thing I taught them is that you're always respectful to cops. Even if they are assholes, even if they're treating you like an asshole, pretend that you don't notice it, continue to say "Yes, sir," "No, sir," and follow their instructions. Don't make sudden moves. My sons have run into the same kinds of things that all of us run into--i.e., if they go shopping at any kind of store, a department store, they get followed around by the store detectives. That always bothers them. And there's nothing I can say that will make them feel better, because there's nothing I can say that can make me feel better. They still follow me around. There are a lot of fair-minded white people who honestly did not believe that racism was so entrenched as it is, and they will say, "I'm not like that, and most of my friends aren't like that." Well, they only know what their friends told them. They don't know how they really are.

Margalynne Armstrong

LAST YEAR, when I was looking at houses in Palo Alto, there was an open house and the Realtor was running out of the fliers about the house, and so when I was looking at it, essentially I was told that I should not take a flier because I couldn't be serious about being interested in this house. In fact, I already had a house in Palo Alto and probably would have qualified in terms of trading up. I wasn't alone at the house; there were some white people there as well. When the Realtor left the room, someone said something about how weird it was, telling me that. It's not a huge thing in the world, but it's one of those things where you can't help but think that someone is making judgments without any information other than your race. There's also the kind of situation of "driving while black." You hear a million stories about that, mainly in Palo Alto. It's not just driving while black, it's driving while black and not driving a late model car. If you've got a car that's a couple of years old, you never get stopped. But when I first moved to Palo Alto, I was living in a very nice part of town, renting, and I made a left turn (I call this "making a left turn into a white neighborhood"), and I got pulled over by a cop. I had my registration and everything and showed I lived about three blocks away from where I was going and after the cop looks at all this he says, "Well, it looked like you went through the light and it had already turned yellow, and this is my first day back from vacation, so I'm not giving anyone a ticket." I know someone who used to be a cop, and he told me, "If you ever get stopped, just keep your hands on the steering wheel because they can see that, and they're comfortable. That's really reassuring to them." So I sat with my hands on the steering wheel after I handed him the stuff, and I just kind of waited this out, and I was allowed to go because I could prove I belonged there, but the presumption was that I didn't.

Denise Johnson

I REMEMBER going to Disneyland with my son when he was 6 years old. Here's a little boy wandering around a store, and I let him walk around to see whatever he was looking at, and I remember this security guard following him around. I remember saying, "Give me a break. He's a child. What are you doing following him around?" I told him I was going to call his supervisor because it was making my kid afraid. This type of stuff happens over and over again. I know it shouldn't. But it does. I had a recent incident where I was followed from my home in Redwood City by a police officer in an unmarked car. I left the house about seven in the morning with my son, and I thought, "Gosh, it looks like this guy is following me." And I thought maybe I was just being paranoid or something. But then when I made a U-turn to drop off my son the car became a police car. They put the little dome on. And a Palo Alto police officer got out, and he had a SWAT team insignia on. He said that I had "x" number of dollars in parking tickets and they had to impound my car. Now I did have some tickets because there's no parking around Stanford, so you're going to get some tickets. But he quoted a number that was far more than I could imagine what I owed. But he didn't listen to that. So he followed me to the hospital because I had a patient on the operating table at 7:30, and then I gave him the keys to my car, because I had no choice. By this time, I'm pretty shaken because I'm thinking, why would they follow me from my house? We subsequently found out that they just hadn't registered all of the checks that I had paid. When we tried to find out if they'd ever done that before, they said, "Oh, well, we picked up one other person." But we did some more investigating and found out that they'd never picked up anyone else like that. It was this whole thing of staking out and watching your house. They claim that they didn't know who I was, but the whole thing was kind of weird. You wonder. How did I feel about it? It doesn't just slide off. I was very angry. And I was frightened. My late husband and I lived in a pretty fancy home in Redwood City. People would always think that he was the housekeeper, or that I was the housekeeper. Like a salesperson or a maintenance person who was coming to do your window curtains, or something like that. I think it's so common to most African Americans' experience, I don't even think about it any more. They see somebody in a very substantial environment and they think that you can't own it, so they say, "Can I speak to Mr. or Mrs. Johnson?" And you are Mr. or Mrs. Johnson. At Stanford, sometimes patients used to think I was a nurse or a medical student or something. That was 10 years ago. Now that I'm older, they think that I'm a resident. But you can't be a full-fledged doctor. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the March 9-15, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.