![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

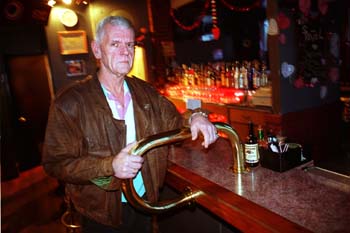

Photograph by George Sakkestad Weed Whacked: Foxtail co-owner Dennis Andrews says he was shocked to discover the nightclub's conditional-use permit had expired. He says the Redevelopment Agency had told him it was still valid. Sticker Shock Once upon a time, life was good at the Foxtail nightclub behind the San Jose Arena. Gay couples and drag queens partied together in peace--until they ticked off T.D. Mitchell. By Jim Rendon T.D. MITCHELL WALKS past a broken mattress in the front yard of a Julian Street house and stops at the wall of an adjacent building which forms the yard's edge. With the worn, pointed toe of his cowboy boot, the lean, 67-year-old Texan draws a line in the dirt. "That's the property line," Mitchell says, looking at the gap no wider than a yard between his line and the gray wall of the building. "The noise level here is supposed to be no more than 60 decibels [about the volume of normal conversation]. But when they play music, this wall here pounds like a drum," he says, spreading his palm against the building's smooth surface. In a tour of the property surrounding Foxtail, one of San Jose's few gay nightclubs, Mitchell points out the places where he says patrons park illegally, urinate and smoke, leaving behind cigarette butts--those places where he says the noise is the worst. Standing alongside his two-story ramshackle Victorian directly behind the club, Mitchell points to a hallway leading to the large fenced-in patio. "The sound is projected right down that hallway and into the house," Mitchell says. Mitchell, who owns the auto shop and salvage yard across the street, says he wants to move into the house behind the club with his wife, who has a blood-related illness, but can't because of the noise. Instead, he rents out the house. "I've never said anything derogatory about any individuals or patrons," he says. When he talks, he proceeds carefully, with the wariness of someone who has been burned. Since his dispute with the club began, he's been called homophobic. He's been called a racist. He's been laughed at and threatened. He's even had a restraining order filed against him. "All I've ever done is complain about behavior," he says in case he was not clear the first time around. "When patrons leave, they are boisterous. People are losing sleep." But Mitchell has gone farther than merely filing complaints. First, he began keeping notes on noise problems, illegally parked cars and loitering patrons. Then he came out at night with a video camera. Once clubgoers realized that Mitchell was videotaping them entering and leaving the bar, they were livid. "Two fellas wanted to go over there and break his knee caps," says Caryl Fulcher, one of the club's owners. Fulcher says that, in order to cool things off, she was forced to get a restraining order prohibiting Mitchell from videotaping near the bar. "We needed to protect him [Mitchell] before someone went over and killed him. We needed him to stop immediately." Mitchell says he was merely trying to document the digressions he saw in the neighborhood and maintains he was within his legal rights. "I'm from Texas," Mitchell says, almost sounding hurt. "Where I grew up, you treated people with manners." INSIDE THE Foxtail night club, co-owner Dennis Andrews apologizes for its appearance. "It looks a lot better at night," he says of the gray paint and the worn wood of the dance floor. But that is not really a problem. Because parking is almost nonexistent on the Foxtail's block-long industrial street behind the San Jose Arena, his patrons wait until after 10pm to show up. They park in the arena lot across the street once arena shows have let out. By the time they arrive, it's plenty dark. And they are not here to critique the decor. They go to Foxtail to have a few drinks, to dance to a DJ and to have a good time. When Andrews and Fulcher, his business partner, bought the club, then called Greg's Ballroom, it had become a problem. The previous owner had lost his entertainment permit, which allowed the club to feature bands and DJs. Dennis Korabiak, the downtown coordinator for San Jose's Redevelopment Agency, says that the club had a history of drug dealing, prostitution and other nuisance crimes. Fulcher and Andrews wanted to fix the place up and start over. The two spent $30,000 upgrading the sound system and the lights, repaving the back patio and sprucing up the place with the hopes of drawing in a large nightclub crowd of gay and straight men and women. And the formula worked. On a good Saturday night, with a DJ and dancing, the club draws a racially diverse crowd of more than a hundred people. Andrews and Fulcher can bring in $3,000. But neither owner has been able to take much of the money home. Since buying the club in October 1998, most of their profits have gone to attorneys, planning consultants and increased security. Their new club has turned into a headache. "At closing time, four to eight cops would come into the building and put our customers up against the wall and pat them down," Fulcher says. "That happened three times, and always the fellow drove up on the sidewalk and shined his lights through the front door." Many patrons also used to park in the no-parking zones alongside the club. In the middle of the night in a largely industrial neighborhood, it did not seem to be a problem. But soon, even after midnight, police officers were showing up to issue parking tickets. Mitchell, who is not shy about his problems with the club, admits that he often called about the illegally parked cars. Mitchell also complained about the noise, drawing police to the club. Andrews was cited twice by police for noise violations. Rather than merely forcing Andrews to pay a fine, as is often done with noise violations, the city is seeking a misdemeanor conviction. If convicted, Andrews may face jail time. George Rios, assistant city attorney with San Jose, says his office is handling the case because Andrews is charged with a violation of the municipal code, not the penal code. Though he declined to talk specifically about Andrews' case, Rios says it is customary to file criminal charges when the police issue a criminal citation as they did here. But Lawrence Rosen, Andrews' attorney, who also represents Redwood City, is baffled by San Jose's approach. "To this day no one has been able to explain to us why the city is handling Andrews' case in this out-of-the-ordinary way," Rosen says. FRUSTRATED BY WHAT they saw as undue police attention, the owners and Rosen met with San Jose Police Chief Bill Lansdowne. After that, they say, officers backed off. But police, as it turned out, were the least of their problems. In order to run a nightclub in a San Jose redevelopment district like the area around the arena, club owners need two things: A conditional-use permit issued by the Redevelopment Agency, and an entertainment permit issued by the Police Department. Although obtaining a conditional-use permit can be a lengthy and arduous process, obtaining the Police Department's permit requires little more than proving the club has a valid Redevelopment Agency permit. Fulcher and Andrews say they bought the club with the understanding that it could operate as a nightclub. When informed by the police that the entertainment permit for the club had been revoked, they tried to renew it. In January 1999, Jason Burton at the Redevelopment Agency faxed Andrews a copy of the club's conditional-use permit. On the fax cover page, Burton wrote that the club had been issued a new permit in 1995. Andrews took that permit to the police station and received an entertainment permit. Case closed, they thought, until the police told them to unplug their DJ. Burton had been wrong. The club had been issued a conditional-use permit in 1992. Like all such permits, it was scheduled to expire five years later, in 1997. Because of complaints against the business when it was Greg's Ballroom, the permit was amended in 1995. Instead of faxing the original 1992 permit, Burton sent a copy of the 1995 amendment and nothing else, leaving the club owners and the police with the false impression that the permit had been granted in 1995 and was therefore valid through 2000. But in reality, the permit expired in 1997, a year before Andrews and Fulcher bought the club. Korabiak blames the Police Department, not his office, for the error. He says that the department should have checked back with the Redevelopment Agency for original paperwork before issuing the permit. Although the city relented and allowed Foxtail to continue operating temporarily, the two owners had to start over and apply for a new permit through the Redevelopment Agency. INSIDE THE GREASE-STAINED office in his auto repair shop, Mitchell flips through a red folder overflowing with papers. He pulls out one stapled group, smudging it with auto grease from his fingers as he flips through it. At the top it reads, "Citizens Log of Disorderly Activity." Mitchell explains that his home behind Foxtail was broken into many times. Every police report generated questions and inevitably increases in his insurance rates. He asked police how to stop the crime. Mitchell says officers advised him to start a neighborhood watch, to keep logs of disturbances and to get the illegally parked cars out of the neighborhood. Mitchell and a handful of other neighbors began writing down noise levels that they recorded using a decibel meter and noting any other activity. Then, Mitchell began videotaping. "The club owners called me a liar from the beginning," Mitchell says. "I wanted to put everything on video so they could not call me a liar anymore." By videotaping, Mitchell crossed a line with many patrons. "Parking in front of the club and taping patrons as they go in and out at least indicates to me he is not sensitive to the issues of the gay community," Rosen says. "There are people who are not out who will avoid a place if they know they are being photographed." Even Robert Frost, a sound consultant that the club owners hired to take noise readings around the club, commented on Mitchell. In a 1:30am sound-log entry, Frost writes, "Note: To my right, an older gentleman, gray hair and mustache with a dark cap was videotaping the leaving patrons. I thought he was some kind of 'peeping Tom.' " Patrons got angry and eventually put up a sign on the patio fence facing Mitchell's salvage yard. On it was a line drawing of a balding head with two eyes peeping over the fence top. It read, "Old Coot, Get a Life." The restraining order against Mitchell prohibits him from videotaping within 300 feet of the club. But, the restraining order only helped for a short while. Andrews says other neighbors have recently begun taping patrons again, setting off a whole new round of resentment. MANY INVOLVED with the club's fight to get a new permit dismiss Mitchell as a crank, but if he is, he is a crank who has suddenly gained a lot of power. Because Foxtail was without a conditional-use permit, the owners had to go the Redevelopment Agency and begin that process from scratch. And it was a surprisingly uphill battle. The club's previous owner had created much animosity with the neighbors, police and planning officials. The owners and their consultant, Sandra Escobar, a former redevelopment staffer, say that the club is completely different than it was under its previous owner. Club owners have met with neighbors and tried to address their concerns. They built a sound wall and redirected speakers to try to keep sound from traveling down the hall and onto the patio. They now have five security guards that keep patrons from lingering on the sidewalk and in the arena parking lot after closing time. And they take their own sound readings nightly with a decibel meter that is kept behind the bar. If the noise is too loud, the DJ is told to turn down the music. Andrews says they are willing to do more, including soundproofing the back wall, if their permit is approved. But they are waiting, fearful of investing the money and then being turned down. Despite these improvements, the redevelopment staff on Jan. 25 recommended denying the permit. Cited in the staff report are numerous complaints the agency has received about noise and complaints in meetings about parking and loitering. Many of these were generated by Mitchell, who circulated a petition to neighbors noting their opposition to the club. The club owners are furious that Mitchell has any say in the issue at all. Although he owns property behind the club and across the street, they note that his business closes at 5pm, when the club opens. Because he rents out the house behind the club and does not live in the area, the noise can not really be a legitimate problem for him, they say. As proof of the dramatic changes they've made with the club, Andrews and Fulcher point to a new ally, the San Jose Police Department. "Foxtail has done a good job complying with our requests and in being responsible business owners," says Lt. Jack Farmer with the vice squad. "They have been diligent in ensuring there are no problems." At a recent Planning Commission meeting, vice squad representatives voiced their support for the club, noting that police calls had diminished significantly in the past six months. The Planning Commission voted unanimously to approve the permit, despite the Redevelopment Agency's objection. But when the Redevelopment Agency came back with the conditions for operations, the club owners were sorely disappointed. They will now be forced to close at midnight on two of their busiest nights, Sunday and Wednesday. Andrews says that he is uncertain whether they will be able to continue to operate the club under these conditions. Escobar is skeptical that much can be done. When there is a compromise like this on a permit, she says, it is very hard to get any additional changes. "They've split the baby, but the baby may die," she says. If they cannot manage to work out some change, Andrews says, he may have to sell the club. But he says he would take great pleasure in finding a new owner, if pushed to that. "If we do have to sell, I'd really like to get even," he says, looking over at Mitchell's house at the end of his patio. "I'd like to sell it to the Hell's Angels." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the March 9-15, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.