The Rabbis

Lithuanian-born Rabbi Iser Freund still worries about Jewish survival at the age of 101.

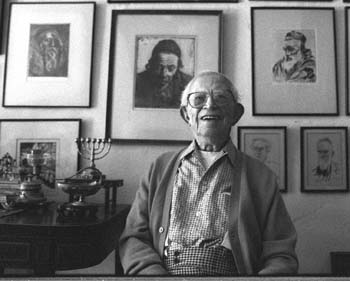

Rabbi Gitin:

Rabbi Joe Gitin, 91, wears navy slacks pulled above his waist and a tucked-in button-down shirt. A white handkerchief peers from his breast pocket, with a perfect crease beneath the flap. His wife, Rosalie, sits girlishly, throwing in compliments about her husband and successfully usurping the entire conversation at times. Rosalie's favorite topic this afternoon is her years as a religious teacher at Emanu-El.

"I would teach the children, God gave us a mind to think and a heart to love and he gave us this beautiful world, and it was up to us to make it stay beautiful," she gleams.

Gitin snaps the conversation back by pointing to a portrait of a young woman hanging on the mantle above Rosalie's head. "Who do you think that is?" Gitin twinkles.

"Rosalie?" I guess.

"That's right," he laughs. She laughs too, and looks over her shoulder at the painting of her in her 20s.

Rosalie won't reveal her age.

"A woman never tells," she says definitively.

Rabbi Joe Gitin has been loved and adored by his congregation for 26 years and counting. While I was researching this series of articles, nearly every person I spoke with mentioned Rabbi Gitin, "that wonderful man."

Now retired, the rabbi still gets called upon to visit the sick, perform a marriage or attend a social engagement. During his time as rabbi, the temple grew from 150 members in 1950 to over 1,000 in 1976.

"Whenever I spoke, I always emphasized the essence of Judaism, which is to be good. I taught that if you want to show your love to God, there's only one way to do it: Love your fellow man. That was the essence of my teaching, and that is the essence also of Judaism."

Rosalie looks on at her husband proudly. "He was honored by the mayor, you know." She points to a framed certificate next to the couch.

Rabbi Freund:

Rabbi Iser Freund wears a navy, patchwork blanket across his lap, not for any religious purposes, but because he is an old, old man of 101 years. His thinning white hair is a little wild today, standing on end in certain spots. A glass of cola with a thin, bent straw sits nearby. As I take a seat, the rabbi takes hold of my hand and does not let go for a few minutes.

"He likes to hold hands," his nurse says.

Iser Freund was born and raised in Lithuania until age 11, when he and his mother, sister and brother landed at Ellis Island. The Freunds left Lithuania in a hurry when it was clear that the eldest boys would be forced to join the Army.

Once in America, the family moved to Cincinnati, where Freund and his siblings spent one year in immigrant school, learning the English language. Although the family had been orthodox in the old country, their Judaism gradually reformed in America. Iser and his brother both went on to be rabbis. Freund graduated from Cincinnati's Hebrew Union College in 1916. He arrived in San Jose just before World War II, in 1939. Before he even had a chance to completely set up his new office at Bickur Cholim, a fire consumed the temple.

"The fire started in the yard in a garbage can and went through the wall all the way to the front of the building. I don't know how it started. Maybe a janitor smoked," Freund said. "Across the street there was a stadium where some Jewish people worked, and they ran over and took the torah out."

Fifty-eight years later, the story of Kurt Opper rescuing the torah has become legend at Temple Emanu-El.

When the war ended, Freund and congregation members began efforts to rebuild a temple. When the structure was complete, Freund changed its name from Bickur Cholim [visiting the sick] to Temple Emanu-El [God is with us].

"What does a temple have to do with visiting the sick?" Freund asks, raising his voice slightly. "Visiting the sick is a good organization for men and women, women particularly. But a temple does much more than that."

Today Freund doesn't go to temple anymore. It's all he can do to make it from the chair to his bed every day. But like any good rabbi should, he still worries about the Jews. His biggest worry, the centenarian says, is interfaith marriages and assimilation.

"Intermarriage is a big problem for the rabbi," he says. "In most cases it's a Christian man marrying a Jewish girl. In most cases they eventually became Christian. Whenever someone in the congregation visited me, I would talk with them about that problem and try to get their daughter to stay Jewish.

"Too much intermarriage," he concludes. "A rabbi worries."

By Cecily Barnes

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Christopher Gardner

A 91-year-old rabbi who still makes house calls

Centenarian worries about interfaith marriages

From the March 12-18, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)