Eracism

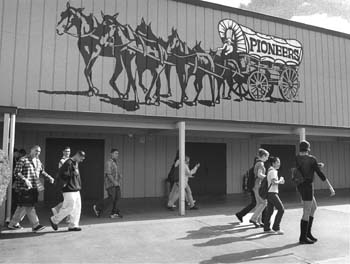

Deriding on the Wall: Parents of African-American students at Cupertino High School say the administration has glossed over racial issues and ignored racial stereotypes in the school's student newspaper.

The appearance of racist graffiti at Cupertino High has some parents calling for action. But school administrators wish the problem would just go away quietly.

By J. Douglas Allen-Taylor

SHEILA CAMPBELL STANDS in the kitchen of her Cupertino home, figuring out what she is going to cook for dinner. She has just gotten in from work, and she is tired. The last thing she wants to deal with is problems with her child at school. "I wish I had never put my daughter in the Cupertino schools," she says with bitterness in her voice. "I moved here from Menlo Park because I thought she'd get a better education and because I thought the race situation here was better. I was right about the education. But on race? They're not right."

Campbell and a second black parent, Charlene Reed, are charging that administrators and teachers at Cupertino High are either ignoring or downplaying recent racist incidents at the prestigious school.

"They don't know how to deal with the problem of black students because there are so few of them there," Reed says. "And they don't want to ask for help from other districts, because then they wouldn't look so great." Cupertino is 3 percent African American, 56 percent white, 27 percent Asian and 12 percent Hispanic. According to Campbell, her daughter is the only black student in all but one of her classes.

Cupertino High is also one of the most highly rated schools in the state. This year's SAT scores put Cupertino in the top 25 percent in the state. Last year, its scores ranked 18th in the state.

The black parents' complaints were triggered by an incident late last year when anti-black and anti-Asian slurs were discovered scrawled in permanent marker on a chalkboard in a school bathroom. One of the writings called for the lynching of African Americans "from a Georgia peach tree"; another referred to "gooks." Another message read: "You nigger. Your beauty ain't shit."

Campbell reasons that this last message was aimed directly at her daughter, Tiffany, who had been recently elected Homecoming princess.

Campbell says school personnel have told her that this is the first time an African American has been selected for a beauty queen position at Cupertino High. Campbell's daughter is also a member of the school's basketball team and president of the Black Student Union.

A day after Reed's daughter, Virginia, informed the school's principal that there was something "very offensive" written in the bathroom, anti-white writings appeared on the chalkboard in answer to the original slurs.

The Campbells and the Reeds stress that they did not think the writings represented the feelings of most students at Cupertino High. Their complaint is with the school's principal, Barbara Nunes.

Both parents think the school should have responded more quickly and more decisively. Nunes, they say, allowed the graffiti to stay up for at least three school days and then refused to call a meeting of parents to discuss the incident.

"We should have gotten all the concerned parents together to see how deep this problem runs," Campbell says, "but Mrs. Nunes said it wasn't her policy to involve the parents. She said she didn't want the situation to escalate. It looks like she just wanted to cover the thing up and act like it didn't happen. She's not really treating this as a serious matter."

Sticks and Stones

NUNES SAYS THAT she was not aware of the specific nature of the slurs when Virginia talked to her on Dec. 1, but that she had the bathroom locked and the chalkboard painted over immediately when she was informed of the situation by Virginia's mother two days later. Nunes says the Santa Clara County Sheriff's Department was contacted, the staff was briefed, bulletins went out to students and parents, and an article was printed in The Prospector, the school newspaper, which included condemnation of the incident by students and school officials.

In the Dec. 12, 1997, Prospector article, however, the school's security officer, Neil Sackett, appeared to take the situation less than seriously. Sackett was quoted as saying the writings appeared "as if it were two friends goofing off, trying to stir things up."

Nunes calls the incident an "aberration," saying that "if they had continued, we would address the issue differently." Nunes says there are already a number of diversity-promoting programs in place, and there "really isn't much of a diversity problem" at Cupertino High to overcome. "We're very well blended," she says, adding that she wishes that "people wouldn't keep dragging this thing out."

According to the regional director of the Anti-Defamation League, Nunes' reaction is typical. Public school officials are often "very reluctant to tackle the issues of hate speech because they don't want to appear to be a problem school," Barbara Bergen says. But, she adds, "it's important that school administrators address this issue. We know what words can do. In and of themselves, they can hurt. And they can lead to escalation and to violence."

Bergen, whose organization tracks hate crime and hate speech, says she is seeing a "disturbing trend" of a rise in hate speech among public school students in the area.

Nunes' failure to call a meeting of the parents would seem at odds with the way Fremont Union High School District officials think such matters should be handled.

"My first advice to principals in these situations is to listen, listen, listen," says Assistant Superintendent Mike Hawkes. "You've got to respond quickly. You've got to get students and parents in quickly. The district takes it seriously anytime these kinds of hate crimes come along."

But Hawkes does not directly criticize Nunes' actions. "Every site is different," he says. "You're dealing with different people and issues."

Charlene Reed, however, disputes Nunes' assertion that there have been no other racial problems at Cupertino High.

"A year ago, my daughter showed me an article on ebonics that was about to be published in the school newspaper," Reed says. "It was highly derogatory and biased against blacks. I went to the school and met with the journalism class and its teacher; I told them about my concerns and even gave them suggestions as to some positive things they could say about black language. They even videotaped the class session. But they went ahead and published the article anyway."

The article, "Ebonics ignites national debate," was published in the March 14, 1997, issue of The Prospector. Ebonics, it said, "has been heard for decades from highly educated blacks to uneducated students in American schools."

The article included a "sample" paragraph of ebonics, which read, in part: "Ebonics be a language dat da Oakland scoo district wants to teach to African-American students ta try an close da learnin gap between blacks and whites in da public scoo's."

In the same issue, in a section called "Delving Into Our Nation's Melting Pot," the paper included a drawing of several representatives of various cultures. Asians and Africans were depicted in stereotypical fashion, the Asian wearing a coolie hat, the African with a bone in his nose and a spear in his hand.

Nunes says she is "not necessarily pleased with some of the opinions" expressed in the ebonics article, but that there was nothing she could do about it. "It's a free-speech issue," she says.

According to Type

IN AN INTERVIEW, Nunes at first said that she could only legally censor a student article if it contained libelous material. But later she admitted that she would eliminate items in a student-written article that were "especially offensive," such as the inclusion of swear words. She says she saw nothing wrong with the drawing, saying that with characterizations "there's always somebody who won't like it."

Ironically, the anti-black charges against Cupertino High come in the midst of a two-year-old drive within the city of Cupertino to promote diversity.

For the past two years, the Public Dialogue Consortium (PDC) has been holding town hall meetings and focus group sessions throughout Cupertino. In those sessions, Cupertino citizens identified cultural and racial diversity as an area of special concern.

Three weeks ago, the PDC began sending De Anza College students into Cupertino High and nearby Monta Vista High to run meetings with students. Barnett Pearce, a consultant with the PDC, says that it is only coincidence that his organization's project at the school came shortly after the appearance of the racial slurs.

"We had always planned to branch out into other institutions in the Cupertino area, including the schools," he says. "Our goal is to create opportunities for the students to engage in a good kind of communication on issues the students are concerned with. We're working collaboratively with school officials to focus on the students' citizenship skills."

Pearce said he had heard about the racist graffiti "in passing," but says, "We don't want to blow the incident out of proportion, even though we take it seriously. If all we do is jump on that one incident, we get a distorted project. Instead, we want to get at the root of the problem."

Nearby Fremont High School has established an academic class called MOSAIC (Making Our Schools An Inclusive Community), whose goal is to bring about a unified student community by holding workshops and weekend retreats where the students openly discuss topics such as stereotypes, culture and race.

And as this winter's incident at Cupertino High illustrates, the classroom beats the bathroom as a forum for such discussions.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Christopher Gardner

From the March 12-18, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)