![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

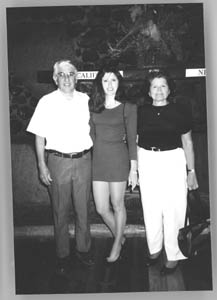

Hometown Girl: Forty-two-year-old Jeanine Harms, missing since July 2001, was raised in Campbell, graduated from Prospect High School and attended San Jose State University. Whatever Happened to Jeanine Harms? Missing for 18 months amid signs of foul play, Los Gatos resident Jeanine Harms is almost certainly dead. How small-town police work and scant evidence have stalled a high-profile investigation--and possibly let her killer walk free. By Loren Stein SOMETHING was wrong, Janice Burnham knew in her bones, in the panic rising in her chest. She had left message after message all weekend long for her friend Jeanine Sanchez Harms--at her home, on her cell phone--and she hadn't heard a word. This wasn't like her closest friend of 27 years; Jeanine would call her back no matter what. That following Monday, July 30, 2001, Burnham tried calling Jeanine at work, at Amdahl in Sunnyvale, but no one answered her work phone either. She then called a co-worker of Harms' at Amdahl, where Harms' had worked for 12 years, most recently as a purchasing manager. It was somewhere between 11 and 11:30am. "Is Jeanine at work today?" Burnham asked Marsha Sanguinetti, who said, "No. We're kind of concerned about her. It's not like her not to show up and not tell anyone." Burnham said, "I gotta go," and began to cry. Burnham, who quickly dissolved into hysteria, knew that Harms would never have skipped work. Harms, who loved her job, was responsible and dependable. Burnham called Chigiy Binell, Harms' friend and the owner of the duplex on Chirco Drive in Los Gatos where Harms rented a quiet, small, attached cottage. Like Burnham, Binell said she had not seen Harms since Friday, three days before. Binell called the police. Burnham called Harms' parents, Jess and Georgette Sanchez. By noon, the cluster of family and friends, including the police and Harms' brother Wayne, arrived at the cottage. Harms' car, a black 2000 Ford Mustang with silver racing stripes, was parked in the driveway. When the police opened the front door, the cottage was empty and immaculately clean, recalls Burnham, one of the few people let inside. There were no signs of a struggle, no blood and no trace of Harms. The bed had not been slept in. The clothes Harms had worn Friday night--a knee-length, short-sleeved, light-blue flowered cotton dress and black high-heeled sandals--were nowhere to be found. Her purse, car keys and cell phone were missing. Two credit cards remained on the kitchen counter. An unwashed shot glass sat in the sink. But it was the other missing items that especially troubled everyone at the scene. Gone was Harms' prized Oriental rug, which lay before her small sofa. Gone were two sofa cushions. And gone was the sofa slipcover. "It was chilling," says Burnham, who let out a scream at the sight. "I couldn't imagine any other reason for those items to be missing other than to be used in foul play." Lawyered Up Jeanine Harms, a charismatic, quick-witted 42-year-old raised on the valley's west side, has been missing for 18 months. Harms' disappearance is the South Bay's highest-profile missing-persons case. Despite a lengthy investigation by the Los Gatos-Monte Sereno Police Department, remains officially unsolved. Her body has not yet been found; none of the missing items has been located; and despite a flurry of police activity around two men who spent time with her on the last night she was seen alive, no one has been arrested. In what could mark a turning point in the case, the investigation has been referred to the Santa Clara County district attorney's office, which is expected to decide any day whether the case should go forward or be dropped for lack of evidence. Harms disappeared under mysterious and confounding circumstances that all but shout foul play, but finding the direct evidence irrefutably linking a suspect, or suspects, to her likely murder has proved elusive. Friends and family believe that someone out there almost certainly knows more than they're telling the police. For these people, who have done everything within their power to find Harms and prod the police into more action, the ordeal has been hell on earth, a cruel and unrelenting nightmare. "It's been unimaginably devastating," says Burnham, a friend since high school. A single mother and a senior software engineer at a local high-tech company, Burnham, 43, has been a driving force in the search for Harms. "It's still hard to believe," she says. "I've had a lot of time to let it sink in, but there are still moments [when] I think, this can't be happening." She adds, "So many times, our hopes have come up [that] something will happen, [that] they'll make an arrest. Our hopes never turn out." Jess Sanchez, Harms' 76-year-old father, holds his wife's hand in the living room of the Campbell home where their daughter grew up and says, "Think of the worst possible thing that can happen to you, the very worst, and that's what it's like. It stays with you." The police, who waited six months to classify Harms' disappearance as a homicide, focused on two local men, both of whom were seen with Harms the night she disappeared. The first was 39-year-old William Alex Wilson III, owner of Wilson's Jewel Bakery in Santa Clara and progeny of a prominent and politically connected Santa Clara family. (His father, a Santa Clara City Councilmember from 1963 to 1971, served as mayor from 1965 to 1966.) The second man--and according to a police department spokesperson the one being more closely scrutinized now--is 43-year-old Maurice Xavier Nasmeh, an architect with Sugimura Associates in Campbell and editor of the newsletter of the American Institute of Architects Santa Clara Valley Chapter. Both men were initially cooperative with the police, but that quickly stopped after they "lawyered up," says Los Gatos-Monte Sereno Police Department Capt. Alana Forrest. Neither has been arrested; both remain in the community and employed. In early January, the police handed over to the Santa Clara County district attorney's office the investigators' report, which fills three binders and contains more than 200 interviews. "We felt we had reached a point in the case where we'd done all the follow-up, all the forensic examination of the evidence and all the interviews we could do at this point," Forrest says. The materials are in the hands of Assistant District Attorney Karen Sinunu, recently handpicked by District Attorney George Kennedy to head up prosecutions for homicide, domestic violence and sexual assault. In an unusual move, Sinunu assigned three DAs to comb through the case one by one before comparing conclusions: Deputy District Attorneys Mike Gaffey, Ed Fernandez and herself. "I decided because of the complexity of the case to have experienced professionals review it in a serial fashion so they don't influence each other," says Sinunu, who will not comment further on the substance of the case. "That way you're more likely to pick out details by yourself." After the three confer, they will have four options: press charges, go to a grand jury, send the case to the police for more work or decide the case isn't prosecutable. Despite the fact that no new evidence has been uncovered, and no body has turned up, Forrest says, "We believe the decision to take the case to the DA was a good one because we have a pretty solid case, strong enough to potentially press charges or go to a grand jury." She adds, "We hope they'll see the circumstantial evidence we see." At this time, police won't confirm what the circumstantial evidence is, or specifically who it points to. If the circumstantial evidence is convincing, or if any new evidence turns up, the question on the minds of everybody connected to this case--family, friends, co-workers, police, private investigators, local politicians and lawyers--is, Who is going to be arrested? And how is it that this person (or persons) has been able to walk free for the past 18 months?

The Last Night On the Friday night, July 27, before she vanished, Harms had dinner with Janice Burnham at Bucca di Beppo in Campbell's Pruneyard Shopping Center. She was nervous and edgy, recalls Burnham, because she was about to meet William Alex Wilson III (who goes by Alex) at 7pm at the Rock Bottom Brewery, also in the Pruneyard. Harms had a couple of drinks and picked at her dinner. Harms was not, Burnham says, looking forward to her date with Wilson. Although good-looking, he was not her personality type and had been "obnoxious" to her in an earlier interaction. During dinner, Burnham recalls, Harms told her that Wilson's "whole personality really turned her off." Wilson declined to be interviewed for this article. The only way Harms knew Wilson, Burnham says, was from a chance meeting several weeks earlier. Harms had gone out after work for a glass of wine and met up with a group of people at a Los Gatos restaurant. When she tried to give her business card to someone else, Wilson plucked the card out of her hand, Harms told friends. He proceeded to call her repeatedly, Burnham says, to get her to agree to a date. At one point, she reluctantly set up a meeting with Wilson but then stood him up. Wilson, Burnham continues, called again, and Harms made up a story and told him she'd had a family emergency. Wilson pressed for another date; feeling guilty, she agreed to meet with him the Friday night before her disappearance, apparently hoping to give him the final brushoff. She asked Burnham and Loretta Meyer, another longtime friend, to go with her, but they both had other obligations. "She didn't want to be alone with the guy," Burnham says. Wilson arrived at the Rock Bottom a half-hour late. By that time, Harms, who enjoyed people and made friends easily, had begun socializing with a new, unfamiliar group of people that included Maurice Nasmeh and Savannah Brien, a colleague of Nasmeh's from work. Wilson joined the group. After drinking for a while at the Rock Bottom Brewery, the group, except for Brien, moved to Court's Lounge, a quarter-mile down Bascom Avenue in Campbell, for more socializing. At some point, a small argument erupted between Harms and another patron over music. After that, Harms apparently drove Wilson and Nasmeh back to the Rock Bottom Brewery to get their cars. Here the specifics of who went where and why become sketchy. Police won't share their theories or evidence, and the DA has opted not to comment pending the outcome of the investigation. Harms' friends and family and private investigators who've looked into the case are left to speculate about what happened next. One theory of friends is that Harms invited Wilson and Nasmeh to go back to her place, but that only Nasmeh showed up. What is known is that at some point, Nasmeh got into his green 1993 Jeep Cherokee and Harms into her Mustang, and they drove toward her cottage on Chirco Drive. It's unclear whether Wilson ever intended to join them, but he did not. Friends, however, believe that Harms thought he was coming. Why? Because, friends theorize, Harms, although sociable, would not have invited Nasmeh to come to her house alone. Physically, he was not the kind of man Harms would have been attracted to, they say. Harms was drawn to blond, muscular guys, like her former husband, Randy Harms, to whom she was married for five years. (They separated amicably more than a year earlier, and Harms is not considered a suspect.) Nasmeh is stocky, dark-haired and balding. On the way to her home, Nasmeh and Harms stopped at a Jiffy Market on Chirco Drive, a few doors from her home, to buy a six-pack of Heineken beer. The owner/manager of the store knew Harms and remembers them stopping by that night. According to Nasmeh, the two of them went to her house and drank the beer. He says she was half-asleep on the couch when he left, sometime after midnight. Missing Traces When she arrived distraught at Harms' house the following Monday, Burnham remembered that her friend had planned to meet with a man named Alex on Friday night, and that's all. She subsequently found his name and phone number noted on Harms' calendar at work. "The police said, 'Oh no, his family is influential; his father was mayor,'" Burnham recalls. When the police caught up with Wilson later that day, he told them that the last time he saw Harms, a green Jeep Cherokee, similar to the description of Nasmeh's vehicle, was following her home, according to police press releases. The police investigation initially focused on Wilson, according to sources, press reports and police press releases. The police quickly released his name and, according to their own press releases, went to his house with a search warrant. They impounded his car and conducted forensic tests, and obtained a DNA sample from Wilson. Private investigator Mike Yorks, a former police detective and sergeant with the Los Gatos-Monte Sereno Police Department, was hired by the family in September 2001 to see what he could turn up. He says he spoke with a neighbor of Wilson's who recounted that Wilson told her after Friday night, "That was the worst blind date of my life. She has loud, obnoxious friends. I had no one-on-one time with her. I didn't say goodbye to her. I went to my car and drove home." Burnham and Loretta Meyer confronted Wilson only a couple of months ago at his bakery to beg him for any help he could give them or the police. Wilson, who is reportedly furious at the way he has been treated by the police and depicted in news reports, refused. He was instantly defensive and ordered them to leave the bakery, Burnham says. He did tell them, however, that Nasmeh said to him something like, "If you're not interested [in Harms], can I go for it?" Wilson said he told Nasmeh, "Sure, I'm not interested," she says. He also told them he thought Nasmeh seemed like a "regular guy." But unbeknownst to Wilson and to Harms' friends, within days of her disappearance, police had made a discovery that had little to do with Alex: a fingerprint on the passenger door of Harms' car that belonged to Maurice Nasmeh. Despite more than 24 hours of news reports about Harms' disappearance, Nasmeh did not come forward when she was reported missing. And what's more, he was identified by police because his fingerprint was "in the county system," confirms Capt. Alana Forrest. San Jose private investigator Dave Meyer, Loretta Meyer's husband and a friend of Harms' since high school days, also spent several months investigating the case. (He was not hired by the family and was not paid.) He turned up two criminal court records from the Superior Court of Santa Clara County that show that case files on Maurice Nasmeh have "been purged due to age." For his part, Nasmeh told police that he did go to Harms' house that night at about 10pm. They bought and drank the beer, he says, and he left around 12:30 to 1am, leaving Harms safely half-asleep on her sofa. He reportedly told police that they did not have sex. When he left Harms, nothing was unusual, he said. A DNA sample was obtained from Nasmeh, and items were seized from his home and car, according to a police press release. (Unlike Wilson's, Nasmeh's name was not initially released.) But Burnham thinks Nasmeh's version of events doesn't quite add up. For one, Harms did not like beer. She preferred white wine and champagne, and even if she made an exception, she would not have wanted to mix her drinks. Also, not one trace of a beer bottle or cap turned up in Harms' home. Nasmeh reportedly told police that he took all the beer bottles home with him when he left in the middle of the night. Another detail that doesn't make sense to friend Burnham: the too-clean condition of the house. After rooming with Harms for long periods of time on two occasions (including right before she moved into the cottage), Burnham says, "I know her habits. There would have been CDs out, beer bottles; there would have been signs of two people socializing. But there was nothing." She adds that if Harms had cleaned up so thoroughly, she would have also washed the dirty shot glass remaining in the sink. She also doesn't believe that Harms would have fallen asleep on the couch with a man she didn't know and wasn't interested in, who was still in her home. It is possible, Burnham speculates, that Harms' aggressor, whoever it is, did not mean to seriously hurt her, but she fell and hit her head, killing her. The rug, the couch pillows and the couch slipcover could have been used to wrap and dispose of her body, or perhaps they were taken from the cottage because they contained evidence of an attack. "We've gone over this a thousand times, all the different scenarios," says Harms' father, Jess Sanchez, speculating about a worst case scenario. "What in the world would have happened to have led another person or persons to commit a violent act? A moment of rejection, a fit of violent anger? Was it an accident or just plain rage from the other individual?" When contacted, Nasmeh would not comment on the case and referred all questions to his attorney. Nasmeh's attorney, John Hinkle, a high-powered San Jose criminal lawyer with a background as a San Jose police officer, also would not comment on the ongoing investigation "It's a tragic situation for the family," was all he would say. Private investigator Meyer says he turned up some puzzling inconsistencies. When she saw a flier with Nasmeh's photo on it, a female bartender at Court's Lounge told Meyer that she did not recognize Nasmeh as one of the men in the group at the bar that Friday night, Meyer says. Another female bar patron also says she didn't recall seeing Nasmeh at the bar after being shown his photo, and says that she saw Harms there when she left after 11:30pm, which is much later than when the group reportedly left the bar. Investigators, a source close to the investigation says, would also like to know what, if anything, Maurice's brother Ray Nasmeh knows. Ray Nasmeh, a former real estate agent with Coldwell Banker in Saratoga, was recently found guilty of hit and run in Santa Clara County Superior Court for a road-rage incident with a motorcyclist. According to Deputy District Attorney Erin West who was the prosecutor, Ray Nasmeh is also a registered sex offender (he was convicted of indecent exposure) and has been convicted of spousal abuse, vandalism and resisting arrest. She said he has threatened to injure several people in the district attorney's office, including District Attorney George Kennedy, Sheriff Laurie Smith and West, and that there are presently more than 20 restraining orders filed against him.

Critical Mistakes The first 24-to-72-hour window of any missing-persons investigation is always the most crucial in solving the case, say investigators. Despite rare success stories such as the safe recovery last week of 15-year-old Elizabeth Smart of Salt Lake City, Utah, the longer the case drags on, the colder the trail usually gets. Jeanine Harms was not reported missing until three days after she disappeared; the time lag and the fact that there were no obvious clues or evidence that could lead to a quick arrest have made the case especially difficult for police. "It's been very frustrating," says Los Gatos Police investigator Steve Walpole, who's worked the Harms case since she was first reported missing. While they certainly took many of the right steps, some close observers argue that under the leadership of former Chief of Police Larry Todd, the Los Gatos-Monte Sereno Police Department made critical mistakes in how it pursued Harms' case. (Todd, who has since retired, was not available for comment.) According to private investigator Meyer, who showed up at Harms' cottage not long after the family, the initial response of the police--despite the missing house items--was that Harms was probably kicking around someplace and would show up at any moment. He says that it took too long for the police to take the situation as seriously as they needed to. Although they were telling people Harms was almost certainly a victim of violence, they did not officially label the investigation a homicide case until many months later. Also, police did not properly secure the crime scene, they note. Meyer says that he watched as more than a dozen police walked through the house, over the grounds and up and down the street--not including family members and friends. "The least number of people involved in a crime scene investigation is best," says a source knowledgeable with police procedures. "You're only supposed to have essential personnel in and out of the crime scene until the investigation is complete. If they weren't doing that, they weren't following their own protocol." Meyer believes that the police also took too long to bring search dogs to Harms' cottage, waiting until a day or two later to do so. "I just believe that whatever scent or evidence was present got corrupted, if not obliterated, by all that activity," he says. Friends and family members also believe that the police focused too exclusively on Alex Wilson for the first week or two of their investigation, which could have allowed the perpetrator to make a clean getaway. What's more, they argue that the police brought in outside help too late in the investigation. (Three months after Harms went missing, they reportedly had only one homicide detective, who was new to the job, working the case full time.) It took six months for Chief Todd to agree to allow help from two experienced homicide detectives from the San Jose Police Department. And it was also close to a year before crime analysts from the Department of Justice developed a suspect profile. Chief of Police Scott Seaman, who took command of the Los Gatos department after Todd's retirement in July 2002, publicly announced that solving the Harms case would be one of his first priorities. He asked Deputy DA Mike Gaffey and DA investigator Mike Schembri to assist in October. "They didn't have the confidence to work the case because they didn't have the right, experienced personnel," says one observer, who adds that it took too long to follow up on various leads. "I don't think it was that complicated a case. Even if they never find Jeanine Harms, the police didn't take the right approach or have experienced people on the case in the beginning." Adds Meyer, "I don't believe the department is incompetent, and I believe they wanted to solve this crime in the worst way. But they don't get a lot of major crime in Los Gatos--it's a very affluent area, and it's a small force." Frustrated by the investigation's lack of progress after the first few months, Harms' family contacted several local politicians to ask for help in getting more police resources and personnel assigned to the case. They contacted U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, DA George Kennedy, former Campbell Mayor Jeannette Watson and state Assemblywoman Rebecca Cohn. They also reached out to Los Gatos City Councilmember Sandra Decker to see if she could help them get police to search the landfill nearest Harms' home with heavy equipment. (Harms' father says he believes this has still not yet been done.) The Los Gatos police did take the case seriously right away and handled the crime scene properly, responds Capt. Forrest, who also noted the 72-hour time lapse before they were alerted that Harms was missing. They focused on Wilson and Nasmeh at first because both were with Harms that night, she says. "As the investigation progressed, and we talked to more people, we realized we should be focusing more on Maurice," she says. Although she will not comment on former Chief of Police Todd, Forrest adds, "We felt we had the capacity and resources to handle this case. Later on, with a shift in leadership here--and sometimes different perspectives and viewpoints and resources to draw upon--we wanted to create more opportunities to look at the case in a different light." Going It Alone Larry Todd came to the Los Gatos Police Department with a history of refusing outside help. In 1989, while an officer with the West Covina Police Department, Todd was found liable, along with then-Police Chief Craig Meacham and the city, for its handling of the 1981 kidnapping case of a 10-year-old boy who was later killed by kidnappers after a ransom drop went awry. A jury awarded the boy's father $5.74 million because, among other things, the police failed to bring in the FBI for the ransom drop. The boy, Ronald Tolleson Jr., was found killed a week later in a garage two doors from his home. (Todd was the watch commander on duty when the boy's father called in his son's disappearance.) Todd was not a micromanager; he expected his staff to handle the department, says one source. "He didn't allow anyone to help when the [Harms] investigation was young, when he should have. ... He does not like being told what to do." (Todd also served as president of the California Police Chiefs Association.) After Mike Yorks was hired by Harms' family to gather more evidence, he says he contacted Todd to suggest ways they could collaborate. The response, given through another officer, was, "If you interfere with our investigation, you'll be arrested," Yorks recalls. The Sanchezes say that Todd neglected to communicate with them during the investigation. He would not return their phone calls and did not meet with them, they say. (He also may have been angry when the family asked local officials to pressure the department.) "What really got me was the perception that Chief Todd was too busy to be bothered with Mr. and Mrs. Sanchez," says Meyer. "They couldn't get an audience with the chief." "We didn't get the feeling when Todd was chief of police that the case had as high a priority as it should have," says Jess Sanchez. "We never saw his hand, his leadership. He didn't call us, saying, 'This is how the case is progressing.' ... never got from the chief--from the very top--assurances that everything was being done. In our case, it's like he never existed." That all changed when Chief of Police Scott Seaman took over eight months ago. Seaman, a former captain with the San Jose Police Department, is said to be fresh and energetic, educated, well-rounded and in touch with the community. He gave Harms' case top billing and redoubled the department's efforts, putting on four full-time detectives to go back over the case. And he has stayed in much closer contact with the family, the Sanchezes say, including attending a candlelight vigil on the anniversary of Harms' disappearance. "He's very proactive," says Meyer. "When he came on, he said to the press, "We're going to solve this case; it's a priority for the department,' and I believe he's lived up to his commitment." "This is a very important case to the Los Gatos-Monte Sereno Police Department, and every member of this department shares in the hope that we can determine what happened to Jeanine," says Seaman. "I look forward to the opportunity to help the family reach an appropriate closure to this tragedy." Spark of Her Family Jeanine Harms, gone for a year and a half, remains deeply loved and alive in the minds of her family and a large circle of friends. As the youngest child of three, "She was the spark of the family," says her mother, who has moved all of her clothes, personal items and furniture back into their family home. (Her brother Dwayne sleeps in her bed.) As described by her friends and family, she was vivacious, intelligent, kindhearted, generous and exceptionally funny. She regularly attended a Methodist Church. A sleek 5-foot-5 and 110 pounds, she was an avid physical fitness buff and a flashy dresser. Meyer remembers the first day he spotted her at Campbell's Prospect High School, when she was a freshman. She was wearing a white miniskirt with red hearts and red shoes. "She was an absolutely drop-dead gorgeous woman," he says. (She later attended San Jose State University.) Her friends say that she had her personal struggles, which were manifested in occasionally drinking too much and partying. She was doing fine after her marriage ended, they say, but she was lonely and, after a recent breakup with a boyfriend, was hoping to meet the right guy. She had her contradictions, they say. "She was an interesting person; she was so safety conscious," says Janice Burnham. "I always laughed at the deadbolts in her bedroom, the crowbar on the door. If she were alone, she'd be terrified and put out newspapers on the floor to hear them crackling [if someone broke in]. But on the other hand, she would invite a virtual stranger into her home. ... She didn't like being alone; she wanted to have people there." Harms was very trusting, say her friends, and never expected the worst in others. She had a hard time saying no; she didn't want to let other people down. "We're all complex creatures, human, and live day to day as best we can," says Loretta Meyer, who has been grief-stricken since Harms disappeared. "I pray we find her." Some people worried that Harms' friendliness and openness could be misinterpreted. She was not promiscuous, they say, but she was beautiful, and men would gravitate toward her, and she would spend time with them. In Dave Meyer's opinion, she let her guard down more after her marriage ended. He also remembers warning her to be more careful. But he hastens to add, "Regardless of her behavior or risk taking, she didn't deserve to die or be killed by some freak." Her family has somehow made it through the darkest of days. Jess and Georgette Sanchez, while devastated, have consistently shown grace and class throughout their crisis, say friends and family. "I've been surprised by how resolute they've been," says their son Craig Sanchez. (Sanchez was in town visiting his family from Olney, Md., when Harms' was reported missing.) "Of course, they want to try to get justice and search for justice, but they're not consumed with vengeance. This hasn't changed them from being kind and loving people to people consumed with hatred. They're very strong in ways I hadn't realized." They've also done everything within their power to alert the community that their daughter is missing and to ask for help in finding her. Headed up in large part by Craig Sanchez, and with the assistance of friends and volunteers, they've been on America's Most Wanted, plastered the region with billboards and distributed fliers and videos of Harms. They've pressed the media to keep the spotlight on the case by agreeing to be interviewed for numerous TV news shows and newspaper articles. They created an informal foundation to raise money, set up a website (findjeanine.com) and collaborated with missing-persons groups. They've held dinners and vigils, offered reward money (as did Amdahl, now called Fujitsu), worked the political system, kept after the police and consulted psychics. "One thing we've became keenly aware of is how many other parents there are that have lost a loved one, a child, a daughter, a son--either missing or murdered," says Georgette Sanchez. "One hundred and fifty thousand people are missing every year in California. Think of all the families that are in pain." What do they hope for now? "We're almost--not 100 percent, not quite--come to the point where we have to accept that Jeanine is dead," says Jess Sanchez. "We would like to know what happened to her. How did she die? Did she suffer? And where are her remains?" "And we want the law to take care of the one who did this to her," finishes Georgette Sanchez. "We're all very anxious to see what the DA is going to come out with," says Craig Sanchez. "The worse nightmare is if the DA throws up their hands and says we have nothing. If they say that, what would really help us is someone coming forward with some new piece of evidence." He adds, "We want to find out what happened to Jeanine, who's involved--and have the person face justice and be punished. But it's also a double-edged sword. When that happens, we will have to relive a lot of unpleasant things and that will be very painful--to sit through the whole legal process. You'd like to put it behind you, but you can never put it behind you. Even if we go to trial and someone is convicted and punished, it's not like it ends for us."

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the March 20-26, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.