![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

A Fan's Film

Mark Moskowitz searches for a forgotten one-book wonder in 'Stone Reader'

By Richard von Busack

MARK MOSKOWITZ is the Michael Moore of the used-bookstore set. He is a meek, balding dad living in the leafiest part of Chester County, Pa. He works in the lucrative but hectic business of making TV ads for election campaigns (one client of his company was former San Jose Mayor Susan Hammer). Indeed, visually, Moskowitz's Stone Reader resembles a political commercial.

The film is actually a detective story, but it's set against happy-looking homes, setting suns, the broken hills of Colorado and anise swallowtails supping on wildflower nectar. (In one lepidopteric inside reference, when the death of the director's father is mentioned, we see a shot of another butterfly: a mourning cloak.) It is all fit to make you sigh, "Damn, what a pretty country we live in."

The imagery is prosperous and comfy, but who can blame the director for insufficient angst? He leads a rich life, and reading has made it all the richer. There's nothing smug or half-baked in Stone Reader, Moskowitz's wonderful documentary about his search for Dow Mossman, who published a first novel titled The Stones of Summer in 1972 and then dropped out of sight.

The Stones of Summer was well reviewed in The New York Times, but it didn't become a classic. It wasn't an easy read; it was published by a since-forgotten small press that didn't have money to flog the novel; and this tiny publishing house was shortly thereafter swallowed up by the conglomerate ITT, which had no interest in selling fiction.

But there are often interior reasons why an author doesn't go the distance. As the bitter critic Cyril Connolly wrote, "Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first call promising." From Connolly's summing up of the hazards of the writing life, Enemies of Promise (1936): "It is curious that while the brief flowering and quick extinction of modern talent is everywhere so apparent, yet little should have been written on the subject." It's an old question: "This age gives an author no time to mature his work," Alfred, Lord Tennyson complained about his era, 150 years ago.

Thus Stone Reader delivers more than just a search for one enigmatic writer. Moskowitz's film is a springboard for the study of what the director calls "one and done" novelists who had one great book to give the world: your Harper Lee, your Margaret Mitchell, your Ralph Ellison. Or those who went decades between publishing: Frederick Exley (A Fan's Notes), Frank Conroy (Stop-Time) and Henry Roth (Call It Sleep).

The common Hollywood image is of the successful novelist, a Stephen King swimming in royalty checks. In real life, someone could publish a novel he'd nearly destroyed himself over and reap what Mossman got: $7,000. In interviews in Stone Reader, we hear lamentations about the human cost of serious writing from luminaries of the lit world, almost all of whom draw a blank when the name "Mossman" is mentioned.

Sources include the distinguished editor Robert Gottlieb and the physically infirm but still magisterial critic Leslie Fiedler, who died recently. Moskowitz also interviews John Koshiwabara, a book-jacket designer whose claim to fame was coming up with the puppeteer image for Mario Puzo's The Godfather. But he, too, has no recollection of designing the jacket of Mossman's only novel.

Closing in on his quarry, Moskowitz stops in Pittsburgh to visits novelist and teacher Bruce Dobler, who recollects the Iowa University Writers Workshop in the 1970s, where he and Mossman honed their art: "It was the meanest place I've ever been, maybe except for the Maryland State Penitentiary." Moskowitz also tracks down professor William Cotter Murray, who gave his student Dobler a series of lashings he still smarts from 30 years later. Weirdly, Murray himself is as kindly an old Irish codger as you'd hope to encounter.

Between the interviews are moments of self-questioning. The most poignant is a spoken essay occasioned by the day Joseph Heller died, which leads the director to remember libraries and old paperback stores that started him on his country-crossing journeys.

This literary detective is a perfect host, never fulsome, never abrasive. It's immaterial whether Moskowitz's taste is correct, or whether Mossman is a lost genius or not. Stone Reader celebrates the communion between author and reader. It's a one-of-a-kind account of the failure and triumph of writers engaged in the hardest job in the world--except for every other line of work, that is.

This fascinating documentary closes with a bittersweet scene. Moskowitz's son extracts, from a cardboard box with a grinning Amazon.com logo, a shrink-wrapped copy of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. The way books are discovered, published and sold has changed, but the passion to read and be read never fails. And for the lucky few, there's the pleasure of meeting the author whose work meant so much to them. Moskowitz's difficult search is rewarded by Mossman's words of appreciation: "You're way past an ideal reader, I tell you what."

Re: Stone Reader

A PS to Mark Moskowitz's love letter to the out-of-print writer Dow Mossman

By Richard von Busack

I found the Jan. 21, 1888, issue of Harper's Bazar at the annual El Cerrito Friends of the Library sale, for 25 cents. Every year, I'm there, with a thermos of coffee and a bag of sinkers from the East Bay's greatest donutorama, Donut Time (corner of Moeser and San Pablo; you owe it to yourself). The freshness of the early hour, the cold morning sunlight of October and the tingling anticipation of the hunt--these are the same sensual pleasures men search for when they head up into the hills to shoot some deer.

And like buck hunting, Friends of the Library sales aren't for weaklings. Anyone who thinks book readers are evolved and gentle and polite ought to go to one of these events. There are genuine rough-housers on the premises, Jack. Those shtarkers give no quarter and expect none. They're in the used-book trade and think of you as someone snatching the food out of their mouths (even though these big fat buffaloes could afford to skip a meal).

Well, I outfought them, and I smote them root and branch, and I was the first one to get to this issue of Harper's Bazar (as it was spelled back then). In it, I found the following thumbsucker essay. Written by "T.W.H." and titled "To the Benevolent Reader," it soothed some of my own self-doubts about the futility of here-today-fishwrap-tomorrow newspaper writing. T.W.H. couldn't have known anyone would read it in 2003, but he had his humble hopes. The below is dedicated to my fellow journalists, then. And perhaps the essay reflects, in a small dim way, Moskowitz's noble quest for Dow Mossman.

Excerpts from "To the Benevolent Reader"

"Lectori Benevolo S." Thus, in the days when scholars still wrote in Latin, they were wont to inscribe the dedication. Not to the patron, as in the Grub Street days of English literature, but to the kind reader, was greeting given. Our newspapers are apt still to propitiate that kindly tribunal, especially at the beginning of the year ... [and] to review the past and to predict the future.

Everyone who commits himself to a weekly article feels doubtless some misgivings at the outset; he counts up the number of words in a column, the number of weeks in a year, and the amount soon becomes formidable. It is only when he reflects, as is the story of the Discontented Pendulum, that no matter how many weeks there are, one can live but a single week at a time--it is only then that he recovers courage. Then there is the doubt whether anybody will read what he sense forth, and just who will read it, if anybody. I remember that once when I was hesitating about an offer to write something for one of those subscription books which appeared profusely in those days from the latitude of Hartford, Connecticut1, a more experienced friend said, decisively, "Write it, by all means. Not a person whom you know will ever see it." Strengthened by this assurance of seclusion, I wrote as requested, and have no reason to doubt that my friend's prediction was fulfilled.

One who writes for the first time for a new periodical often has this same wonder in his mind, and perhaps presently finds, as in my case that he seems to have a vehicle of communication with all his friends and neighbors. Instead of the stimulus of seclusion--which is indeed something--he has the greater stimulus of publicity and finds his thoughts, such as they are, reflected from the most unexpected quarters. In a country like ours, so plastic [freeform] and so vivacious, any great weekly publication becomes simply a telephone, where the slightest world spoken becomes at once transmitted to a great many ears besides thought for which it was originally intended.

When the discovery was once made that ... there is an audience provided in advance by the energy of a publisher and editor, the sense of responsibility becomes very great, and with it the feeling that perhaps, even if what one writes is not very good or important, it may assume a certain merit through reaching some one who needs just that word ...

Now to have one reader each week is really a great thing when we consider how much some stray scrap in a newspaper, perhaps not in itself especially wise, has occasionally influenced our own lives. Nothing encouraged me more to undertake these papers than a remark of my friend Mr. James Parton, who told me that one part of his literary life of whose usefulness he felt absolutely certain was the series of papers that he contributed weekly during many years to the New York Ledger. He rarely heard from them again, he said--it seemed a good deal as if they had been written and thrown into the sea--yet it was on them that he relied to satisfy himself that he had been of some real and permanent use to somebody, in his long career as a writer.

The present writer has been more fortunate in this, at least, that he has heard again and yet again, chiefly through the medium of the post-office, from his public. That public has been from the beginning very free to express itself in the way of encouragement, correction, and when necessary, of reproof. Above all, it has opened such a magazine of suggestion as greatly to clear his path and supply him with material. Whenever he has been fortunate enough to hit the mark--and no writer always misses this--it has happened very often that his public itself has supplied the very arrows that hit it, like the eagle of old poetic tradition winging the shaft with its own feathers2. No doubt many of these suggestions from "the benevolent reader" have proved inapplicable or unavailing; but even in this case they did no harm, and it is certain that very often they gave him the greatest possible aid. After all, every form of literature implies two factors-he who writes and he who reads; and just as the stimulus of an audience often provides the best part of an orator's address, enabling to say to it what he could by no possibility have said to himself, so it is between the writer and his circle of readers. This is especially true for someone who writes with some regularity for the weekly press; and he soon learns to rely upon this response and to count upon his audience to supply, as it were, a part of their own reading.

Grant that the furnishing of such weekly installments is very much like the preparation of parched corn3, which must be eaten hot, or not at all, yet even parched corn has its use, and has been found to sustain life. One who writes in this way knows with some certainty that an early oblivion will await what he writers; and yet if some good is done in the interval, or even some pleasure given, of what importance is the rest? It is doubtless true that all literary work should not be like this; that one should occasionally do some piece of work, as Gail Hamilton suggested, on which might be inscribed: "For future ages only. No contemporaries need apply!"

But even then fate takes its revenge and has its own way with men's deeds. Men do not now read that Novum Organum in which Bacon tried to sum up the whole knowledge of his time, but they read his essays, which he described in his dedication as "grains of salt"; and while Johnson's own works lie unopened on the shelf, it is his gossiping biography by Boswell that is immortal. And by thus comparing small things with great, even the humblest newspaper essayist may derive his little consolation.

--T.W.H.

NOTES:

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

![]()

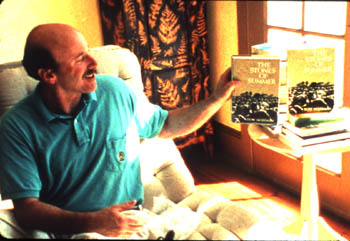

All Lit Up: Filmmaker and avid reader Mark Moskowitz shows off his rare copy of 'The Stones of Summer.'

Stone Reader (Unrated; 128 min.), a documentary by Mark Moskowitz, opens Friday at the Towne Theater in San Jose.

1. Door-to-door peddlers of the 1800s gathered enough money in advance to publish a book; Mark Twain's Roughing It was financed in this manner.

2. Anyone know the source of this image, of an eagle shot with an arrow for which he's furnished the feathers?

3. In this sense, think of it as popcorn.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the March 20-26, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.