![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

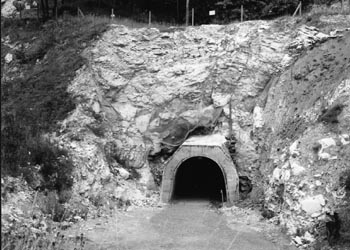

The entrance to Birkenau concentration camp as it looks today. Cents of Outrage Visiting the death camp at Dora with his father, a reporter wonders why it took 50 years for the corporate and national beneficiaries of the Holocaust to even try paying the Jews back By Jim Rendon

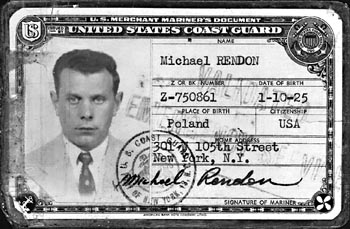

Then for the first time we became aware that our language lacks words to express this offense, the demolition of a man. In a moment, with almost prophetic intuition, the reality was revealed to us: we had reached the bottom. It is not possible to sink lower than this; no human condition is more miserable than this, nor could it conceivably be so. Nothing belongs to us anymore; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak they will not listen to us, and if they listen they will not understand. They will even take away our name: and if we want to keep it, we will have to find ourselves the strength to do so, to manage somehow so that behind the name something of us, of us as we were, still remains. --Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz MY FATHER STANDS BACK a few feet from the chain-link fence, not leaning or hooking his fingers through it as I do to get a better look. From where he stands, the fence forms a thin mesh over the view: a green hillside, chalky-white boulders framing a large concrete tunnel that disappears into the blackness beneath the mountain. He is quiet and uncomfortable, as he's been since we arrived here. And now, faced with this inconspicuous opening in the earth, he shifts his weight on his feet and starts to turn away, walking with an unusual timidity. This tunnel is the entryway to a vast underground factory, a portal through which he passed daily half a century ago. My 75-year-old father beat unimaginable odds surviving here between the summer of 1944 and the spring of 1945. This is Mittelbau-Dora, a former Nazi concentration camp 130 miles southwest of Berlin. Beginning in 1943, 60,000 Jews like my father, and slave laborers from as far away as Greece, Iran and America, were brought to this place to work. Nearly half of them died here. Through this tunnel entrance, beneath the mountain in front of us, slave laborers expanded an old calcium sulfate mine and built an underground factory. When it was complete, parallel tunnels 40 feet wide and 28 feet high stretched for nearly a mile. Connecting them, like the ties of railroad track, were 46 factory chambers, each 150 yards long. My father was 19 when he arrived here from Buchenwald in the spring of 1944. Like thousands of others, he began working in this factory. Slave laborers spent 12 hours per day underground, building V2 rockets, the world's first ballistic missiles, a treasured Nazi secret weapon used to bombard London and designed to win the war. "Nobody could believe what was going on inside that tunnel," says my father, Michael Rendon. "Inside was like hell. I don't think hell was like this. People were falling like flies. There was no air. The dampness ... ," his voice trails off. Between October 1943 and March 1944, 11,000 laborers excavated the mines. Living inside the tunnels, the laborers only saw the light of day during the weekly roll call. In addition to blasting, they used little more than primitive tools, even their bare hands, to hollow out the old mine. The average inmate died within six months. Many were crushed beneath boulders in the mine, or beaten; most were simply worked to death. Once the factory was complete, slave laborers were moved to barracks outside the tunnel. Workers like my father knew that they were building important weapons for the Germans, and they risked their lives to sabotage the rockets. Prisoners faked welds, left out parts, loosened screws and urinated on the wiring, my father says. When the Germans took the rockets to Poland for testing, most of them malfunctioned in mid-flight. Of the 6,000 V2 rockets produced at Dora, only 447 were actually launched toward London. When word of the sabotage got back to the camp, the brutality and the death toll rose. For the slightest infraction, people were shot, beaten to death or hung from cranes over the factory floor, slowly strangling while people worked beneath them. "Whoever thought about it, they knew they were going to kill people like flies in that place," my father says through a Polish accent that is still thick after decades in America. "The Germans [who ran the camps and lived nearby] were playing with their little kitties, and they had their little dogs. They took better care of them than the people. They were playing music, and nothing bothers them that people are being slaughtered out here. They went about their business, you know. The thing that really burns me up is that it came so natural to kill another human being like that. To squash them like a beetle," he says, pausing for a breath. "The guy wouldn't even do that for you," he says, remembering his captors. Mercy was unheard of. According to accounts of survivors, by the end of the war so many people were dying here so quickly that the crematorium could not burn all the bodies. Piles of corpses were scattered throughout the camp. In the days before American troops arrived, the Germans shot hundreds, maybe thousands in the hopes of covering up what had happened here. Liberating soldiers found 5,000 corpses when they entered the camp on the morning of April 11, 1945, and only 1,000 survivors. German soldiers herded more than a thousand prisoners away from Dora, marching them westward for three days. In a small town, they barricaded those who survived the march in a barn and set it ablaze, killing nearly all of them. "It was incredible to us that people had been systematically starved, beaten, with no medical assistance and food; these people were in just a horrible situation," says Ragene Ferris, a medic with the 104th Infantry division, which walked into the camp on the morning of April 11, 1945. The battle-hardened troops were shocked by what they saw here. "We took 700 people to the doctor, their stomachs just about gone, and 300 of them died," Ferris says.

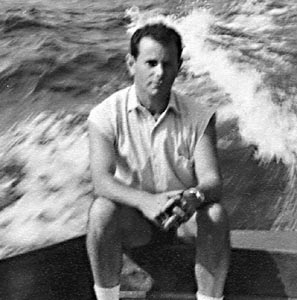

Blood Money MY FATHER AND I walk across Dora's gravel-covered square, the size of a football field, where he stood for hours each day enduring the Germans' roll call. Usually a talkative, outgoing person, he has crawled inside of himself here. Even when we visited Birkinau, a subcamp of Auschwitz, he explained to me how he had been shoved out of the boxcar and lined up with the healthy men, avoiding the gas chamber by chance. We searched the camp grounds until we found the remnants of the building that he lived in. But here, whatever words he can muster will not rise to the surface. He just looks. Inside his coat pocket, his fists are tight balls. My father has lived with the memories of this place for decades. But he does not want sympathy. Though he tells parts of his story to anyone who asks, he has never gone out of his way to talk about it. After all, he survived. His father and stepmother and brother did not. The aunts who raised him in Krakow after his mother died have never been seen again. Of an extended family of nearly a hundred, only a few cousins survived the war, most of whom escaped before the Germans invaded Poland. There are many who suffered more, many who suffered worse fates, and he does not want to take away from their stories. But as a survivor, his story is important. And now he and the hundreds of thousands like him are the subject of lawsuits, international negotiations and billion-dollar settlements meant to atone in some way for these horrors. At Dora and other camps, he labored not only for the German government, but also for many German corporations. According to Red Cross sources, Ilfeld and AEG used slave labor at Dora, but scholars are just now beginning to research corporate involvement in many camps. Today, lawyers and politicians are demanding some accountability from the private businesses that profited from the Holocaust. My father is now one of the hundreds of thousands eligible for settlement money from Swiss banks, German companies and soon insurance companies, too. Like many survivors, he believes that these companies should pay something to the victims. And he is outraged that it has taken half a century for these corporations to admit their guilt and offer some compensation. But he is clear that no matter what sum of money he receives, it will never atone for what he experienced. "It will not wipe the slate clean," he says. To some, the effort to seek reparations is a surreal arrangement in which the destruction of a people is being placed in the balance with money. Money is the language of Western culture and is undoubtedly the language of business, but should it be the language in which we settle up for the worst destruction of humanity in the 20th century? How much is one year of suffering worth, compared with two? How much is a dead father or mother, a stolen home, a decimated culture worth? Does this legitimize the practice of slave labor by putting a price on it, or does it finally make someone accountable? And why has it taken 50 years for all of this to come to a head? Denials and Resistance AFTER HE ESCAPED from Dora, my father left Europe. Eventually, he joined the U.S. Merchant Marine. For more than eight years, he floated in the limbo of the world's oceans, trying to find himself again, to get past what had happened to him. "Nobody cared [about what had happened to me in the camps]," he told me one night on our trip to Poland and Germany. "I didn't tell anybody. If you tell somebody, they don't believe you anyhow. I never told anybody. I mean, how do you explain this to people?" Many survivors waited decades to talk about what had happened. Primo Levi, who wrote one of the early personal accounts of life in the concentration camps, did not publish Survival in Auschwitz until 1958. "After the war, people hardly wanted to talk about it. We wanted to rebuild our lives. We wanted to be Americans. We wanted families," says William Lowenberg, a survivor and a San Francisco real-estate developer who served as the vice chairman for the National Holocaust Museum. "I, for one, can tell you that in the early years after the war, I never discussed it. I lost my entire family. One thing we needed--we needed a family again." Now that so many survivors are dying, the youngest, like my father, who spent his teens in the camps, are now in their 70s, and there is a new immediacy to setting the record straight. And to obtaining some gesture of reparation before they die. Since 1960, my father has received meager payments from Germany. Through a fund called Wiedergutmachung (meaning, literally, making good again) he began receiving $150 per month. Payments increased over the years as the number of survivors fell, and it is now closer to $500 per month. But many survivors never even received that. Many missed the deadline to apply for the money. Thousands ended up in the Eastern bloc after the war and received nothing. The vast majority of forced laborers were not Jewish and therefore have never received compensation from the German government or anyone else. Those in Eastern Europe have lived in poverty for decades. And of course, 6 million Jews died in the camps. None of their heirs receive a penny. The attorneys and advocates who have worked to extract money from corporations since the war have met with denials and resistance. For decades, Jews were turned away at banks across Europe when they tried to recover funds deposited by family members before the war. When Lowenberg tried to recover funds from a Dutch bank that received all of his family's assets before the war, he was first stonewalled. Then, he was told that the account totaled $12. He was so disgusted, he let the matter drop. But in the past decade, two important circumstances changed: the Soviet Union collapsed, and 50 years rolled by on the calendar. Without these two events, there would be no slave-labor suits and no pending insurance settlements. And it is unlikely that the true history of Swiss complicity with the Germans would ever have hit the papers. After 50 years, many government secrecy acts expire, opening up vast caches of archives to scholars. The United States and Britain released reams of paper in 1996, allowing academics to enter a whole new cycle of scholarly foraging. That paper flow was augmented by the fall of the Soviet Union. After World War II, Europe was divided in half. Everything that fell to the communists was off limits to the West. But with Glasnost and Gorbachev, things began to change. Elan Steinberg, director of the World Jewish Congress, credits what he calls "the Schindler effect," among other things, for much of the headway that's been made. "The release of Schindler's List and the opening of the holocaust museum sensitized the general public and archivists. When we approached the government [with requests for information] there was an understanding and sympathy. That was not always the case," he says. That openness led the Clinton administration to respond to decades' worth of document requests from the World Jewish Congress and other Jewish organizations. More than a million documents related to Holocaust-era assets were released by the U.S. government in the 1990s. Ed Fagan, a New York attorney who gets considerable ink on this issue, says that he saw an article in The New York Times about survivors who were unable to retrieve funds from pre-war Swiss bank accounts (the Swiss banks required relatives of survivors to produce death certificates, something which the SS was not in the habit of handing out). He clipped the article and filed it for later. Fagan handled legal affairs for a number of survivors, and he says it was not long before a client who was a survivor approached him about their own problems getting money from a Swiss account. Fagan began gathering attorneys to help cover the millions of dollars of up-front costs it would take to fight the well-funded Swiss banks. In the end, 13 firms joined in on the suit. The list of plaintiffs, including my father, is 500,000 names long. Morris Ratner, a lead attorney in the Swiss-bank and slave-labor suits and a partner at the San Francisco firm Lieff, Cabraser, Heimann and Bernstein, says that in 1996, researchers at the U.S. Holocaust Museum who were looking through documents released by President Clinton found lists of Jewish account information that contradicted statements by the Swiss. "It was an issue that was settled long ago," he says. "But this new evidence opened it up again."

Corporate Complicity IN 1948, Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, the owner of Krupp, a German steel and weapons manufacturing company, was convicted of employing slave labor. He was stripped of all his belongings and was sentenced to 12 years in prison. A handful of other German business leaders at companies most associated with the Nazis, like IG Farben (a joint creation of Bayer of aspirin fame, BASF, manufacturer of blank tapes and Hoechest) and Flick were also convicted and sentenced to what today would seem like moderate prison terms. Three years later, they were all released, and most of their assets were returned to them. Though John McCloy, the U.S. high commissioner for Germany responsible for the release, denied it, many think that these people were released to help Germany reclaim its economic stability. As the country on the border with Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe, it was vitally important to America's Cold War chess game that Germany develop and maintain a strong economy. "As long as a capitalist system was pitted against a communist system, a lot of Western Europeans and Americans were uneasy with pursuing corporations. They thought it would play into the hands of communists," says Jonathan Weisen, a professor of history at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, who is at work on a book about how German corporations coped with their complicity in World War II. One attorney, Benjamin Ferencz, worked for decades to force some restitution for slave and forced laborers. After years of unflagging work, Ferencz managed to obtain small settlements from a few German corporations. My father received $1,100 for the work he did for IG Farben while he was at a sub-camp of Auschwitz early in the war. He still has a scar on his finger from a deep cut he received while working as a pipe fitter. He stole bandages and iodine to treat the wound and splinted it with a stick. Germany and the West lived in such fear of Communism that suits by survivors were deferred by law. A treaty signed not long after the end of WWII deferred all Holocaust-related lawsuits against German corporations until after the country had reached a point of economic stability. Not until 1991, two years after the Berlin wall came down, and 52 years after German tanks rolled into Poland, did a subsequent treaty declare Germany economically fit and open the door for lawsuits by people like my father who suffered while toiling to create vast corporate wealth. Butting Heads IN APRIL OF 1994, executives of America's seven largest tobacco companies stood before Congress and swore that nicotine was not addictive. Four years later, executives from those same companies were back in Washington, this time admitting what everyone has known for decades: that nicotine is addictive, that smoking causes cancer. By the end of that year, the major tobacco companies agreed to pay out $206 billion to 48 states. Holocaust survivors may owe more to this chain of events than anything else for the settlements that are now on the way. Eli Rosenbaum, a lead prosecutor of Nazi war criminals with the Justice Department and author of Betrayal: The Untold Story of the Kurt Waldheim Investigation and Cover-Up, sees an unmistakable connection between the tobacco and Holocaust suits. "In the 1990s, tobacco lawsuits settled, and lo and behold, some of the states had hired private firms and promised them a percentage of the recovery," he says. "These cases settled for more than $200 billion. For the first time in history, class-action lawyers were becoming billionaires. I think this emboldened lawyers on the Holocaust suits." Once stories about slave labor and Swiss banks began hitting the papers, Rosenbaum says, his phone began ringing. "They suddenly saw that they could sue someone for the Holocaust. Lawyers started calling me saying, unabashedly, 'How do I get a piece of this?' " In addition to the vast settlement talks was something almost unprecedented in the history of public relations: a complete reversal of strategy in just a few short years. This shift had a profound effect on corporate public relations, Weisen says. "Corporations are finding out that the stubborn public-relations strategy that says whatever you do, do not confess guilt or wrongdoing, is not working. The public is too smart for that. They are gambling that it does not hurt to be more open. It's a trend that you see in multiple contexts. There is a cynical aspect to it as well. You can say they are still thinking about the bottom line and how best to protect it." And as a result of these and other factors, the German corporations came to the table far more quickly than the Swiss. They offered up a settlement far larger than the Swiss, though much smaller than anyone had hoped. "All of this is part of a trend toward increasing use of the legal system in areas no one imagined it could be used," says Rosenbaum, who is supportive of getting more money to survivors. "In 1964, the surgeon general said that smoking caused cancer. But it wasn't until the 1990s that anyone dared to go after them [tobacco companies]. It was decades before anyone thought to sue gun manufacturers and hold them liable for the crimes committed with their weapons. If you'd suggested that ten years ago, you would have been laughed out of the country."

Swiss Stalling DESPITE all the lawyers, and all the publicity, no one has received a dime from the Swiss- bank or slave-labor suits. Like many survivors, my father has been on the phone with paralegals, filled out forms, dredged up his own personal history to explain the series of camps he was at, starting with Auschwitz in 1941 and ending in Dora. He has fished in his childhood memory for the names of family members who did business abroad who may have had Swiss accounts. But how much about family finance could a 14-year-old boy know anyway? Settlements and the resulting payments are an understandably messy process. But they are made a little messier by their quasi-legal nature. These are not judgments reached by a jury verdict. None of the cases went that far, and some say that they really did not have the legal merit to survive in a courtroom. Instead, these are settlements pushed by attorneys, backed by broad scholarly work and a looming moral imperative and ultimately forced by American political and financial muscle. When the Swiss began stonewalling on their lawsuits, New York City Comptroller Alan Hebessy drew together a group of 900 state and local financial officers. They threatened gross divestment of state and local pension funds, a move that could cost billions. The banks' ultimate $1.25 billion settlement was meager in comparison. When talks got bogged down, U.S. Sen. Alfonse D'Amato, then chairman of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, held congressional hearings and inserted himself into the process, making the story a regular feature on the news, turning the lawsuit into an intergovernmental issue. The Swiss finally gave in and began a long and important process of re-evaluating their own role in WWII. What they found was radically different from the neutral image the country had maintained for decades. But once again, the Swiss are stalling the process, Ratner says. Payments once expected by March of this year will be delayed for months, maybe longer. Ratner says the Swiss are unwilling to make account information available to the court, something that he says is necessary to assess individual claims and to determine how the settlement will be divided. Ratner is hopeful that survivors and their heirs will begin receiving checks as soon as this summer. The slave-labor suits have been settled by an agreement with the German government, but are also on hold. The parties are awaiting German legislation authorizing disbursement and additional negotiations between plaintiffs' attorneys and the German government. The sum again is comparatively small, $5.4 billion for nearly 1.5 million slave and forced laborers, most of whom live in the former Soviet Union, most of whom are not Jewish and have never received a penny for their suffering. Divided evenly, that is less than $4,000 apiece.

Sum Disagreement WHILE THE FINANCIAL negotiations continue, there are those who question the whole lawyerly endeavor of suing for monetary compensation for something as hideous as what happened to Jews and others in the camps during the Nazi era. How does one pay for wiping a people off the map of Europe? "The last few years, all you hear about are Jews and their money, Jews and their bank accounts," says Abe Foxman, a survivor and national director of the Anti-Defamation League. "I don't know how many Jews had bank accounts or art, but this skews the whole truth about the Holocaust: Jews died because they were Jews, not because they had money in bank accounts. The debate, the argument, skews the basic facts. People who grew up in the last 35 years who don't know much about the Holocaust will begin to believe it is all about money." But that may reflect more of a problem with education than anything else. And it is, in fact, similar to the argument that Helmut Kohl used to defer additional German payments for decades. Rabbi Andrew Baker, director of European affairs for the American Jewish Committee, says that for decades Kohl refused to look at corporate payments because he argued it would create a dangerous backlash against Jews. But Baker says that Kohl was wrong. Since the settlements were announced, he has not seen any perceptible increase in German anti-Semitism. No one involved pretends that any amount of money can compensate for what happened. "There will always be an arbitrary nature to any kind of monetary figure," says David Perry, director of the ethics program at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. "One could do something like imagine what individuals might have made in regular employment in which they were enslaved and think about a reasonable kind of monetary equivalent to that. But you can't really put a price on enslavement itself and those kinds of humiliation and degradation." But these settlements do not even go that far. Given the number of plaintiffs, and the relatively small settlements, it is unlikely that any one person will receive more than $10,000. Many will receive only a few thousand dollars. It's a sum that represents little more than the leverage which could be practically exerted on a few dozen multinational corporations. It has little to do with the atrocities these companies committed. "We would always like to have gotten more," says Ratner, who worked on both cases. "In both instances, I believe the sums are reasonable in light of the fact that most of the evidence has been destroyed. Most of the victims could not prove their claims because the evidence has been destroyed. In light of other risks in delays associated with litigation, the amount that has been put up, while it does not in any way represent complete justice, it is a reasonable sum and represents a rough measure of justice. There is no way to put a final number on real suffering on the elimination of European Jewry. No amount of money we come up with could. That was not the goal." Even if we accept that some amount of money is appropriate, the sums that are likely to be doled out here fall far short of what others in similar situations have been awarded. In 1995, the German government paid roughly $200,000 each to 11 American survivors of concentration camps. In 1997, Argentina announced its intent to create a fund to compensate relatives of those disappeared during its military reign of terror. Each family will be entitled to $220,000. And the Japanese interred in camps in America during WWII were paid $20,000 each by the U.S. government.

Punitive Pittance BUT ONE THING these lawsuits have done is get the attention of companies that for decades have denied any role in this century's largest genocide. Class-action lawyers, many of whom, like Ratner's firm, took on these cases pro bono, were able to do something that decades of complaints and scholarly research has not. And that may be because they are speaking the corporate language: money, very large sums of money. Nothing gets the attention of a corporation like the phrase "punitive damages." And, regardless of the cases' legal merit, the thought of having to fight a lawsuit in which the Holocaust would be on trial in front of a jury I'm sure did not sit well with anyone's board of directors. By speaking with money, attorneys managed to open a dialogue, one that has finally forced some admission of complicity. As more and more archives are opened, the truth about how much corporations profited from the murder of millions will make its way to the public. And the fact these companies had to pay something will not change what they did. Most of those involved in the suits say this experience may cause a business to think twice before heading down that road. "That is the one positive message," Foxman says. "There are consequences for your actions. There is accountability." My father maintains a practical attitude about the settlements. He has taken the money in the past because, well, what first-generation immigrant learning how to live with unimaginable trauma could not use extra money for himself or his family? No one has ever claimed that Germany was less guilty because it paid money to survivors and to Israel, more than $60 billion over the past 55 years. IG Farben and Volkswagen will not be any less guilty for giving away a pittance. "A few thousand dollars will not change the way I feel about it," my father says. That is not something that money can do. He doesn't expect much from these suits, and he is skeptical that the small sums of money will ever get to him anyway. If they do, he has no plans for how to spend it. In doing this article, I found out that, for years, he had saved the money he got from Germany each month, uncertain of how to spend it. How do you spend money that comes as a result of genocide, that grows over time to represent the people and the places, the whole world that was destroyed? What is the correct way to honor that loss with anything money can buy? Perhaps the best way is to move on, to see it as money to help with the everyday little things. Now that he's retired, he uses the checks to help cover his living expenses. Because, after all, it is just money. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the March 23-29, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

Rest and Recuperation: Rendon escaped from the Dora concentration camp and was treated by the U.S. Army 20th Field Hospital. In the bottom left corner his weight is charted. He weighed 46 kilograms (101 pounds) when he entered the hospital.

Rest and Recuperation: Rendon escaped from the Dora concentration camp and was treated by the U.S. Army 20th Field Hospital. In the bottom left corner his weight is charted. He weighed 46 kilograms (101 pounds) when he entered the hospital.