![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

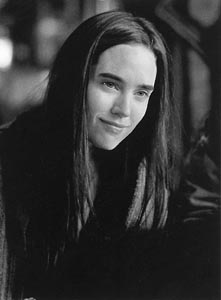

Remembrance of Lovers Past: Jennifer Connelly comes back to haunt Billy Crudup in 'Waking the Dead.'

Remembrance of Lovers Past: Jennifer Connelly comes back to haunt Billy Crudup in 'Waking the Dead.'

The Sixties Sense 'Waking the Dead' tells an unusual political ghost story ONE OF THE strangest films of the year, Waking the Dead is a romance in which the fear of selling out--a keen agony in baby boomers--takes on a supernatural, ghostly tinge. Those Old Enough to Remember get struck in the tear ducts immediately by the Joni Mitchell tune "A Case of You," which plays over the titles. The story is divided equally in time between the early '70s and 1982. In Minneapolis in 1974, a young girl, Sarah Williams (Jennifer Connelly), and two Chilean dissidents are blown up by a car bomb. The martyrdom of Sarah changes the life of her lover, Fielding Pierce (Billy Crudup); after she's gone, he becomes the politician he always wanted to be. In 1982, Fielding allows himself to be groomed by mentors from the Chicago machine. The governor of Illinois offers him a congressional district, thanks to a special election occasioned by the dropping out of the previous congressman (Ed Harris), who has been caught in a sex scandal. The sudden race to office precipitates a crisis. Just out of the edge of his eye, Fielding begins to see the seemingly long-dead Sarah. (You could call this movie The Sixties Sense.) Has some conspiracy kept her hidden? Or is there a more ghostly reason for her reappearance? As we puzzle out the mystery, the story of Sarah and Fielding's tangled romance is replayed. Fielding was a Coast Guard officer with an eye on political office; Sarah was a Catholic activist who dedicated herself to helping refugees from the political coup in Chile and was killed in the midst of this mission. Her reappearance nearly 10 years after she was presumed dead obsesses Fielding. During one tormenting phone call, he tries to ward Sarah off with a half-choked "I don't think you'd like me now." Hasn't everyone fantasized answering a phone call from their old selves or a dead lover in exactly those words? TAKEN UNCRITICALLY, Waking the Dead is low-key and chilling. Director Keith Gordon, late of Mother Night, weaves a mood of unrecoverable loss and sorrow. His scenes of Chicago and New York were filmed in Montreal during the full gloom of winter. (As in The Sixth Sense, the chill of old stones and lowering skies makes the supernatural possible.) Unfortunately, the scenes of conflict between Fielding and his family are as morally black-and-white as TV dramaturgy. There's a moment of bad imitation Arthur Miller in the scene in which Fielding's ne'er-do-well brother, Danny (Paul Hipp), informs his sibling, "If you're closing the door on me, you're closing the door on yourself." (Try that line on your brother next Thanksgiving.) The old-time political bosses who manipulate our hero all but blow cigar smoke into his sensitive face. The two Chileans, whom Fielding meets at a church supper, are supercilious and self-righteous. Just as bad, we only get one little glimpse of Sandra Oh, demonstrating her uncanny knack for accents, as a Korean indentured massage-parlor girl whom brother Danny is rescuing. At one point, Sarah describes herself as Fielding's "Jiminy Cricket," his conscience. Hal Holbrook, as the most benign of the people pushing Fielding into office, describes himself as Gepetto. At times, Crudup, a strikingly handsome but immature actor, seems too close to playing the little wooden boy. A congressman isn't a senator or a president, after all. There are many recorded cases of members of Congress keeping their own personalities after they've been elected. And I don't know if I followed the film's argument that it would be progressive to have a pure-hearted, reluctant Hamlet-boy as a congressman. What you really want in the office, as Gen. Patton could have said, is not necessarily someone who feels your pain, but someone who can make the other side feel its pain. The problems in Waking the Dead are right there in the novel by Scott Spencer, who also penned the fervent romance Endless Love. For contractual reasons, Robert Dillon is credited as the scriptwriter, though Gordon claims in the press notes that he never even read Dillon's script. Reading the outline of the romance, you can see that Spencer missed his best bet. If Sarah had been a radical left-wing bomber wanted by the FBI, there'd be better motivation for her hiding from her beloved. Spencer also didn't even use some of the good old-fashioned reasons for hide-and-seek melodrama (hideous disfigurement, for example). Gordon isn't old enough to have endured the self-inflicted baby-boomer agony about selling out, but he's reproduced those tensions startlingly well. The fear of selling out seems to be a lesser ethical dilemma to today's young. Conditioned by irony, twentysomethings have the confidence that they can subvert, viruslike, any system that absorbs them. So I doubt if the political angst of Waking the Dead is for them. Centrists don't feel these left-wing pangs. Neither would right-wingers, obviously. Where Waking the Dead is at its best and most haunting is in its most basic form: as a romance. I found it tremendously evocative, from the snow to the Joni Mitchell tune. The lissome Connelly's searching face, straight hair and attractive chipped incisor tooth evoke the image of the unadorned beauties of the early '70s. Their boldness and intensity threatened to turn the world upside down--what's satisfying is that they did it, for the most part. Connelly works a hypnotic trick, making the demands of a strong conscience not nagging but alluring and bittersweet. Spencer's Sarah in the novel was just a politicized version of the Ali McGraw character in Love Story, but Connelly makes her tangible and haunting. Waking the Dead is often dramatically suspect--and politically naïve. But Connelly, who's never been better, wakes Waking the Dead, bringing it to life.

Waking the Dead (R; 105 min.), directed by Keith Gordon, written by Gordon and Robert Dillon, based on the novel by Scott Spencer, photographed by Tom Richmond and starring Jennifer Connelly, Billy Crudup and Hal Holbrook, opens Friday at Camera 3 in San Jose. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the March 23-29, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.