![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Cosmetic Damage

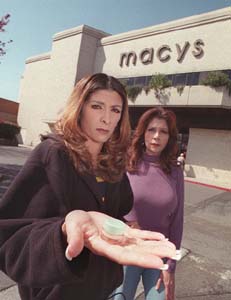

Free Sample: Sisters Irma Carasco (left) and Isabel Avila say they paid a high emotional price when Macy's guards accused them of stealing and paraded them through a local mall.

Free Sample: Sisters Irma Carasco (left) and Isabel Avila say they paid a high emotional price when Macy's guards accused them of stealing and paraded them through a local mall.Christopher Gardner

Falsely accused of shoplifting by Macy's guards, two Mexican-American sisters struggle to recover their dignity and their dreams By Traci Hukill IRMA CARASCO'S FAMILY says she doesn't talk much and never has, even as a little kid with seven big brothers and sisters picking on her. With a feather-slight frame, skin pale beneath a layer of makeup and eyes lined carefully in black, Carasco looks fragile, more like a teenager than the 30-year-old she is. She sits folded up in the corner of a couch in her lawyer's office, letting her sister do most of the talking. Isabel Avila, the elder by four years, takes the lead as naturally as water runs its course. She's protective of her little sister, who she says has "been through a lot." It was Avila who sputtered protestations at the Macy's security guards when they accused Carasco of shoplifting a sample of eye cream six months ago. She was the one who called the store manager when they got home that night and demanded an explanation. And it was her idea to contact her brother's friend, attorney Patrick McMahon. The sisters are suing Macy's for damages in excess of $10,000 for defamation, infliction of emotional distress, false imprisonment and negligent supervision. But the details of the lawsuit interest them far less than the humiliation they endured. What might look to an outsider like a bad but understandable mistake has left these two women angry, wounded and cynical. The damage to their confidence and belief in the American party line about racial equality can't be quantified. Chestnut-haired and calm but energetic, Isable Avila takes over again, describing the events of that occurred on Oct. 1 animatedly and in great detail. "It was a Thursday night. I'd gotten some money for my birthday the night before," she recalls. "It was the first time my sisters had ever given me a surprise party at my house. It's a big deal, you know? So we had taken the kids to catechism and I thought, 'Here's my chance to go out and spend my money!' " With an hour and a half to shop before picking up Avila's two kids and a neighbor girl at Holy Family Church in San Jose, the sisters made a beeline for the cosmetics department at Macy's in Oakridge Mall, where Carasco spent $30 on makeup by Estée Lauder. Avila purchased the Holy Trinity of Clinique skin care products--soap, toner and moisturizer--but had to wait a long time because the saleswoman was helping someone else. Later the apologetic clerk dropped a couple of free samples in Avila's bag, and the sisters headed for the next cosmetics counter, Lancôme. While they waited again at the Lancôme counter, Avila rummaged through her bag and handed the quarter-sized sample of "all about eyes" eye cream to her sister. Carasco walked over to a display, read a brochure about the product and slipped the little jar into her purse. As they browsed through the junior department a few minutes later, Carasco noticed a man watching her. "You know how you feel kind of funny when someone watches you?" she says. "I just kept that face in my mind. It didn't dawn on me who it was until much later." Macy's Parade AFTER EXHAUSTING the cosmetics possibilities at Macy's, the sisters headed for Victoria's Secret and then to Trade Secret, a beauty supply store. When they came out, two men and a woman dressed in plain clothes, including the one Carasco had noticed earlier, were waiting on a bench outside the store. Carasco and Avila estimate 20 minutes had passed since they'd left Macy's. It was almost time to go pick up the kids. One of the men approached Carasco. She thinks it's no accident that he was Latino. "We think they had him approach us because he was Hispanic," she says. "They just want to cover themselves. "He said, 'We saw you shoplifting,' " she continues. "I said, 'Shoplift what?' He goes, 'The cream.' I started laughing. I showed him, 'Is this what you're talking about?' He said, 'Yeah.' I go, 'They gave this to my sister. It says right here Not for Resale.' "And then they still didn't want to believe us." At that point in the incident, Carasco stopped talking and Avila sounded off, insisting on their innocence, telling them she needed to go get her kids and generally raising hell. "Being a bigmouth," she now calls it. Despite her vociferous complaints, the three security guards marched the two back to Macy's, past the Jewelry Palace kiosk with its ropes of 10k "real gold" chains looped over felt, past Leed's, past the Cellular One kiosk, where bored salespeople turned to look at them. It was a new kind of Macy's parade. They were escorted to the Clinique counter, where the saleswoman confirmed that the "all about eyes" jar was indeed a gift. The security guards, unfazed by this piece of information, escorted the two women to the security office via an outside entrance. The moment they stepped outside the store, Avila says, indignation turned to terror. "Because then it hit me: I don't know who these people are," she recalls. "Anybody could have said they were Macy's security." At first she refused to go, but finally she complied. Once in the security office, the man Carasco had noticed first told her to empty her purse. "I just dumped it out and that was it," Carasco says. "They just looked at each other. They were shocked. He thought I had more in my purse." "That's when I said, 'Now what?' " Avila chimes in. "I said, 'You see, I told you guys you had to be positively positive.' I was angry that they paraded us like a bunch of criminals. I mean, being seen by a lot of people--you might not know those people, but inside your mind you're thinking they're gonna know you when you come back. In their eyes, we're convicted, you know?" Race Matters THE ENTIRE ORDEAL lasted no more than 20 minutes, but Avila was incensed. She demanded the guards' names and told them this would not have happened if she and her sister hadn't been Hispanic. When she got home she called Macy's, and the security manager called her back to apologize. He explained that the guards hadn't been sure they'd actually seen Carasco take the cream, that they'd reviewed the tape several times before deciding to take the women in. Several weeks later each sister received a $50 gift certificate. "I still have mine at home," Carasco says in disgust. "I'm not gonna use it." Patrick McMahon has been listening to his clients retell their story. An Irish immigrant, he came to the United States in 1960 with no money and scrambled to get through college and law school. Now he practices law in a lavish office beneath a picture of himself schmoozing with Muhammad Ali. He speaks up in a gravelly voice. "That Hispanic shoppers could be treated with such an outrageous lack of respect is what attracts me to this case," he says. "My clients made it clear that they'd taken nothing and offered to prove it, so why were they taken against their will? I suspect it has to do with a profile, because [the guards'] evidence was very inconclusive before even starting out. "I don't care whether you're Spanish, Irish, Chinese, Lebanese or Pekinese, the way they were treated cuts against the grain of any self- respecting person. And then for them to be offered a $50 gift certificate shows the price Macy's puts on their conduct. It's dehumanizing." It is Macy's policy not to comment on litigation. But public relations manager Merle Goldstone reads the following prepared statement over the telephone: "Industry statistics reflect that approximately 99 percent of all stops made by loss-prevention personnel result in a shoplifter being apprehended and stolen goods reclaimed. Under Macy's policies and procedures, suspicious behavior which may suggest unlawful activity--not race, national origin or other personal characteristics--is the basis for making a stop for suspected shoplifting." On March 11, the Irvine office of G. Michael Brown and Shireen Banki Rogers, attorneys for Macy's, issued a demurrer and motion to strike. The 21-page document lists in detail the reasons the charges against Macy's are invalid. Par for the course, says McMahon's office. "We will attempt to find out from discovery whether there is subtle stereotyping and subtle profiling or actual profiling," McMahon says. "To treat a shopper in that way, is that the Macy's way? If that happened to everyone, you wouldn't get many people coming back. So how do they pick who it happens to?" Assimilation Dreams AT THIS POINT, winning in court would be an academic victory for the two sisters. The real toll, they say, has been emotional. For one sister the Macy's experience has confirmed everything she always suspected about the way things really are, Benetton ads be damned. For the other sister it's been a crushing setback, an insinuation that her struggle up the ladder has all been for naught. Carasco's voice is hard when she talks about the effect it's had on her. "I try to forget it," she says. "I don't think discrimination is ever going to be over. I think it's always going to happen." She maintains that the Macy's debacle is somewhere near the bottom of her list of concerns. "I can't worry about this; I've got too much else going on right now," she says distractedly. But Avila is stung deeply. She has worked hard to make the grade since she was a schoolgirl. She was a straight-A student. She worked at Mervyn's and JCPenney in high school and gave the money to her Mexican immigrant parents to help out at home. Working in retail, she was trained not to judge people by their ethnicity, to give everyone equal respect and service. And after she married, she and her husband, Edward, bought a townhouse in a monochromatic middle-class neighborhood off Blossom Hill Road, the first Latino family to do so. And what she keeps learning is that playing by the rules does not guarantee anyone a place in the club. In junior high, she recalls, another boy got the Student of the Year award even though Avila's grades were higher. There are still some neighbors who won't speak to her and her husband or let their kids play with the Avila children. And in fancy stores, skin color and attire seem to matter more than anyone will admit. "I really try not to pay attention to that stuff," she says in a close approximation to offhandedness. "You either adjust and just look the other way, or otherwise it'll eat you up if you think about it all the time." But the humiliation of her Macy's experience has stayed with her. Never much of a shopper to begin with, she finds that now she avoids going to stores at all. "It's like now I have a paranoia," she explains, looking a little puzzled. "I had to force myself to go shopping at Christmas." After a second she adds, "I know I need to talk to someone about it." Seated on a couch in her living room, whose warm earth tones mirror the color scheme of millions of middle-class living rooms across America, Avila reflects on what it's like to feel split between two worlds. On the one hand, she remembers trips to her parents' hometown in Mexico, all eight kids jammed into the station wagon. She remembers her brothers and sisters feeling ashamed of their parents--her mother's pink curlers, her father's old-fashioned rigidity, their inability to learn English. On the other hand, she tells about a Christmas party where her husband's Mexican friends accused them of being "pochos" or traitors--too Americanized for their own good. And recently someone answered an ad in a Spanish newspaper for Avila's old couch and criticized her faltering Spanish. "My husband feels like I'm not Hispanic enough because I've drifted away from my culture," she says, "but I've had to. It's not that you give it up, you just don't think about it." "One day we'll find our spot in this world," she says. "Mexicans, you know, who have come here have their spot. Americans have their spot in this world. Mexican-Americans, we don't have a spot yet." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the March 25-31, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.