![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Still the Greatest

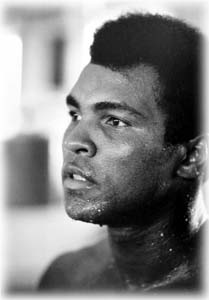

Champion Forever: Muhammad Ali in training for his 1974 championship bout against George Foreman. Photo by Howard Bingham

'When We Were Kings' revives memories of Ali By Allen Barra

THE MOST spectacular sporting event of all time took place in Kinshasa, Zaire, in 1974, when Muhammad Ali KO'd George Foreman. Does that sound like overhype? Consider: Muhammad Ali was the most famous human being on the planet; at one time in the 1970s, The Guinness Book of World Records announced that he had passed up Lincoln, Jesus Christ and Napoleon (in that order) as the most written-about person who ever lived; millions around the world jammed into theaters to watch him regain the heavyweight title from Foreman. Even that kind of attention, however, is fleeting. When young rap singers would drop by the office of music and film producer David Sonenberg and see video images of Ali on the screen, they'd ask, "Who's that?" Filling in that historical gap is why Sonenberg wanted to make When We Were Kings, a documentary about the famous bout: "We've got to explain to this generation, and the next, just who Muhammad Ali was and what he did." When We Were Kings, directed by Leon Gast from his original footage and featuring commentators Norman Mailer, George Plimpton and Spike Lee, is the story of how the Ali-Foreman fight was put together, how it nearly fell apart and, finally, how Ali pulled off one of the biggest upsets in boxing history. In 1974, Muhammad Ali was 32 years old and already a legend. A gold medalist in the 1960 Olympics in Rome, he turned pro in 1961 and, after just three years and 19 pro fights, shocked the boxing world by beating the seemingly invincible Sonny Liston to win the heavyweight title. He was just 22 and on top of the world, but being on top wasn't enough--he wanted to turn it upside down. A day after his triumph, he announced to the world that under the guidance of Malcolm X, he was discarding his "slave name," Cassius Clay, and was converting to Islam; he would henceforth be known as Muhammad Ali. After disposing of the best heavyweights, Ali ran into a roadblock when he refused induction into the U.S. Army. It was bad enough that he had allied himself with Black Muslims at a time when America's inner cities were torn by racial strife, but white America wasn't prepared for a sports hero to proclaim opposition to the draft and the Vietnam War in 1967. Ali was stripped of his title by the simple refusal of state athletic commissions to issue him a license to box. In 1970, finally able to obtain fight licenses, Ali came out of retirement and eventually confronted another unbeaten former Olympic gold medal champion, Joe Frazier. He lost, and Sports Illustrated proclaimed it "The End of the Ali Legend." If it didn't seem that way after the loss to Frazier, it certainly seemed that way when an awesome newcomer, George Foreman, battered Frazier senseless in just two rounds in 1973. How could Ali, over 30 and past his peak, prevail against the man who had crushed the only man ever to beat Ali? How good was George Foreman in 1974? "Think of it this way," says Gast, who sat in the third row the night Ali made history in Zaire. "Foreman had pulverized the two best heavyweights around, Joe Frazier and Ken Norton. Most of us who were rooting for Ali didn't just think he'd lose--we were afraid for his life. Foreman was simply too big and strong." THAT WAS the backdrop when an ex-con and former street hustler named Don King put up an unprecedented $5 million for each fighter if they'd meet in Zaire, where a smiling but unbenevolent dictator, President Mobutu Sese Seko, was willing to make all sorts of concessions in order to show off his shiny new capital to the Western press. King made a daring play: He guaranteed both Ali and Foreman money he didn't have. The backing came only after he signed them. That's when Gast entered the picture. An independent filmmaker, he had been contracted by a London-based firm called International Film and Records to do a film on a music festival, a sort of Afro-American Woodstock, that would take place before the fight. Gast wound up with nearly 450 hours of footage of the events surrounding the fight--not just the music but also the comings and goings of the fighters, the international press and the celebrities who flew in for the festivities. Much of the footage, particularly shots of Ali ingratiating himself with the natives and Foreman stepping off a plane accompanied by German shepherds, helps fill in the historical background of the fight. "Ali was loved by the Zaireans," Gast says, "because they felt he was fighting for them. When they saw Foreman arrive with German shepherds, which is what the Belgian police used to use against them, that was it. The phrase, 'Ali, Boomaye!' 'Ali, Kill him!' was everywhere." In the actual fight, Ali pulled off perhaps his greatest victory ever by outfoxing as well as outfighting Foreman. In the eighth round, he rebounded off the ropes with a spectacular three-punch combination which sent Foreman to the canvas and made Ali only the second man in history ever to regain the heavyweight championship. Gast had one of the greatest fights in boxing history on film as well as all the historical background that made it a world event. What he didn't have was his money. When he couldn't reach International Film and Records on the phone in London, he hired a solicitor. It took a year to track down the firm. After a court battle, Gast was awarded the footage as compensation, but that victory turned out to be just the first hurdle. "More than 400 hours of film to go through," he moans in memory of the experience, "with no sound synched to it, and no backing." Every few years, it seemed as if a backer might appear, but nothing ever materialized. The reason became clearer as the years went by: "There was too much Ali out there," Sonenberg says. "He was too popular to be hip. He had to be away from the scene for a while 'til people could put him in proper perspective." Gast feels that "it was the Mike Tyson era that made people truly appreciate Ali. With Tyson it was the opposite of the way people reacted to Ali. We loved Tyson at first and then came to realize that there was nothing there, that he stood for nothing. As the years went by, Ali stood for more and more." One of the things that helped Gast and Sonenberg get backing was Taylor Hackford's involvement in the project as editor. Hackford, a big fan of boxing in general and Ali in particular, has had a successful career directing documentary as well as feature films, including his well-received Chuck Berry film, Hail, Hail, Rock 'n' Roll. In 1995, Hackford watched day after day of Gast's original film and began collaborating with him on an edit. Hackford also conducted interviews with Lee, Mailer and Plimpton, all intended to put Ali and his legend in perspective. The Mailer and Plimpton segments in particular give When We Were Kings a special resonance, since they were probably the two most prominent journalists to cover the fight; in fact, Hackford acknowledges that Mailer's book The Fight was a major source of background material. "It was great to have them both," Hackford says, "because they have such wonderfully contrasting styles. George is the eternal sporting man, while Norman looks like an ex-pug. I mean that as a compliment, by the way." Hackford calls the finished product "a time capsule that takes you back to a key moment in black consciousness in the '70s." Gast hopes it will be a film with multigenerational appeal. "What we want to show the younger audiences," Gast says, "is what these two guys--Muhammad Ali the icon and George Foreman the jovial talk-show guest--were like when they were at their peak, fighting for the kingship of the world."

When We Were Kings (PG; 90 min.), a documentary by Leon Gast. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.