![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

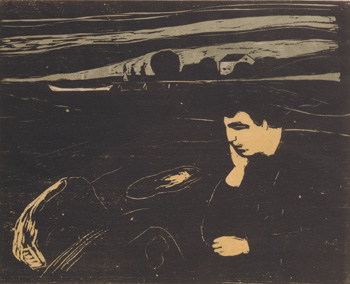

The Munch Museum/The Munch-Ellingsen Group/BONO 2006 Shore Leave: Edvard Munch's 1902 color woodcut 'Melancholy (Evening)' exemplifies the artist's gloomy outlook on life. Screaming A show of Munch prints at Stanford opens a window into the Norwegian artist's troubled soul By Michael S. Gant ONE WINTER weekend, I found myself trapped in a Tahoe cabin waiting for the snow to relent enough so we could go outside and ski. After hours of card games and Scrabble, I was reduced to staring at the knotty-pine walls, which were beginning to close in at an alarming rate. Apparently, other claustrophobes had resorted to the same desperate ploy. In a cramped alcove, I could see the handiwork of an art lover who had abandoned all hope. The walls were plastered with a jumble of pages ripped from magazines and books. The images, all by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863�1944), flowed with lurid colors applied in frenetic whorls, like liquid poison swirling down a drain. Most troubling of all was the repeated image of Munch's most famous work, The Scream (1893). In a landscape of livid reds and bruised blues, a bald figure whose head is shaped more like an alien's than a man's advances toward us on a walkway that slams across the picture plane in a stabbing diagonal. His hands are clasped to his skull-like features, his mouth open in a rictus of universal pain. As Munch wrote, "I felt the great scream through all Nature." This image (Munch reworked it several times in various media), produced just before the 20th century, remains iconic because it seems to anticipate—to warn us about—the horror of wars, massacres and genocides to come. It loses none of its impact as a black-and-white lithograph from 1895, which can be seen in "Desire, Anxiety and Loss," a show of Munch's prints running through June at Stanford's Cantor Arts Center. Even years of kitschy repros on inflatable dolls, coffee cups and T-shirts have not diminished its raw power. In hindsight, The Scream appears eerily prescient, but Munch's despair was as much personal as it was historical. As detailed in Sue Prideaux's fascinating new biography, Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream (Yale University Press; $35), the artist, who grew up in Christiana (now Oslo), Norway, tasted tragedy early and often: his mother died at home when he was barely a boy; one of his sisters passed when he was a teenager; another sister went insane. It didn't help that Munch's stern, religious father freely dispensed beatings to the surviving siblings and then reminded them that "Mama saw them from heaven—and grieved." No wonder then that so many of the prints at the show bear fraught titles like Melancholy, Separation, The Sick Child and Two Human Beings, the Lonely Ones. The most biographical print, Death in the Sickroom, a small lithograph from 1896, depicts the family's funereal curse. Munch's sister Sophie, turned away from us, sits dying in a rocking chair, attended to by Munch's father and aunt. A brother abandons the spare room (evoked with a few sketchy perspective lines). In the center, disconnected and disconsolate, sit the other family members. Tellingly, Munch pictures himself as a blank-faced outline. Munch ran with a fast crowd of bohemians that included the crazed playwright Strindberg and an anarchist provocateur named Hans Jaeger, who boasted that he could drive young writers to suicide. Free love was the rage, and Munch indulged freely, much to his regret, in several disastrous affairs. His first lover, Millie Tallow, was an accomplished adulteress. He was later pursued by a woman named Tulle Larsen, who was "like a leeched fastened on his identity." As Prideful writes, "The foundations were laid for the sexual act to be associated with melancholy, remorse, fear and even death." The push-pull between desire and fear of female power shows in many of Munch's prints. Consolation (1894) is a scarifying small drypoint of a naked woman, kneeling, facing forward, her arms covering her chest and face, while her naked lover draws his arm around her—there is little ease in the anguished gesture. In Kiss IV, a roughly incised woodcut, a man and a woman embrace so thoroughly that their faces seem to merge into one. Munch always pulled away from his lovers, no matter how intensely absorbing the initial passion. Hence a great ambience in his images of women. The two-pronged title Madonna (Woman Making Love) encapsulates Munch's vacillation. A voluptuous woman, seen from the waist up, lies back in ecstasy, her eyes closed, her hair a nimbus of sinuous curves. In a fit of post-coital angst, Munch gives the portrait a rust-red border full of swimming sperm and a tiny huddled fetus, looking like a homunculus in vitro. Most memorable is Vampire II, a maleficent Pietà in which a woman leans over a man who has buried his head against her chest and presses her lips against his neck, her long golden-red tresses splayed out over his shoulders. As first, we think she might be comforting him, but then (urged on by the title), we see her as Munch saw her: as a vampire sucking the man dry, the strands of her golden-red hair flowing over him like rivulets of blood. Despite increasingly frequent and debilitating attacks of despair, Munch remained restless (moving to Berlin and Paris) and creative in the 1890s and early 1900s: "Fleeing the fate of blood and heaven, he trailed his canvases and his painting equipment ... across Europe ... prowling the interchangeable night streets, engaging with their interchangeable whores; setting up exhibitions, taking them down again, creating success, which he never valued." When the inevitable breakdown came, Munch entered a sanitarium where he was diagnosed with a form of dementia brought on by alcohol poisoning. Munch recovered, although he was by his own admission not seeking a true cure. As he wrote: "My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art." Munch was always unsparing in his self-examination, in both his art and his diaries (which are as impressive as his paintings and prints). He sought, with brush and pen, to "write his life." The impulse can be seen in the first print in the show, 'Self-Portrait With Skeleton Arm (1895). Munch's disembodied head stares straight at the viewer, floating in a dense, inky space. Across the bottom of the lithograph is a severed bony forearm and hand, as if the artist had turned an X-ray machine on his body and his soul.

Desire, Anxiety and Loss: The Prints of Edvard Munch runs through June 25 at the Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Edvard Munch: Behind 'The Scream' by Sue Prideaux; Yale University Press; 391 pages; $35 cloth.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the March 29-April 4, 2006 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2006 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.