![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Custom Custody

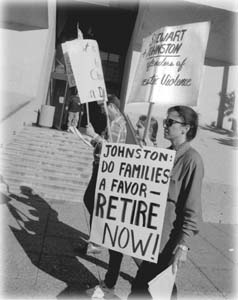

Mother, Mother: Picketing moms say they've been given short shrift by Judge James Stewart and his chosen experts and lost custody of their children as a result. Photo by Christopher Gardner

Some losing parents in Santa Clara County Family Court say there's an anti-mom bias creeping into the rulings of long-sitting Judge James Stewart. Is it payback time for dads or a case of overzealous pendulum pushing? You be the judge. By Michael Learmonth INSIDE THE SANTA Clara County Family Court, the best and worst human impulses are laid bare as judges alternately perform marriages and preside over the worst 30 percent of divorces--the emotional train wrecks so grisly they could not be resolved out of court. In these divorces, people who may have once been in love sometimes show they will do anything to hurt one another, even if it means using the children to do it. So volatile is the climate that Family Court was the first in the county to have metal detectors installed at the door. From these contested divorces, victors rarely emerge. But one group of women believe they have been so wronged by the system that they carry neon signs in front of the family courthouse, sometimes twice a week. They are demonstrating against a judge they say is biased against women and all too quick to take custody away from a mother on the basis of the diagnoses of a few court-appointed psychologists. "I've never had a parking ticket, and I lost custody of my daughter," says Kathy Justi, taking a break from the picket line of 10 women and a few men in front of the courthouse at Park and Almaden in downtown San Jose. "They've already taken mine and Kathy's children," chimes in Maria Duncan. "There's not much more they can do. We are not going to back down." The judge who has inspired protest is James W. Stewart, who at nine years on the bench is by far the most experienced jurist in Family Court. The protesters are asking that Judge Stewart be removed from his post and that the system in which court-appointed psychologists testify in child custody hearings, particularly in cases where molestation has been alleged, be reformed. "They have their First Amendment rights," says Stewart, who called pickets at Family Court routine. "Two months ago we had pickets from a men's group claiming we're biased against fathers. The system is not necessarily fair to parents. Indeed, there is no obligation to the parents besides due process." BUT AN INCREASINGLY vocal group of protesters and attorneys believe due process is not what mothers are getting in Judge Stewart's courtroom. Labeled as "histrionic," "paranoid" or "passive-aggressive" by psychologists in Judge Stewart's court, Maria Duncan of Los Gatos, Kathleen Justi of Fresno and Margorie Mardis of Santa Cruz all lost primary custody of their children. They blame Judge Stewart for relying on the testimony of two psychologists, Terry Johnston and Michael Jones, who performed evaluations on the women. " 'Histrionics.' This is how we are labeled to diminish our credibility," says Duncan. "It happens to women time and time again." "In my view there are a given number of people that do not want to go through a period of self-reflection and change," says Judge Stewart of the protesters carrying signs bearing his name. "It is so much easier to blame the system--much easier and very human." But the use of court-appointed psychological experts to make evaluations and testify in court is widespread and controversial. Judges in Family Court rarely challenge the professional opinion of a court-appointed psycho-expert. Even the evaluators themselves admit the responsibility is daunting. "They do have a lot of power," says Michael Jones, the psychologist who examined Justi. "They are only appointed after quite a few attempts are made to settle the case." Because the opinion of experts carries so much weight in court, judges are under competing pressures. They must be familiar enough with the reputations of the evaluators to trust their judgment. At the same time, they are obligated to use as many evaluators as possible to assure that one or two don't wield undue influence. On this point, Judge Stewart has his critics. "There is a tight-knit group of court-appointed experts who are primarily psychologists, ... the use of which is highly controversial," says Patrick Standifer, the San Jose attorney who represented Justi. "They make it to the court so often that the court is over-relying, leaving custody decisions to this handful of experts." "He has his favorite experts, and whatever they say goes," adds San Jose attorney Anthony Boskovich. "If he [Stewart] is guilty of that, then in fact all judges are guilty," Jones says. "They would like to have as big a group as possible, but there are so many professionals who don't want to do this kind of work because it is so adversarial." "It's an awful lot of authority to give someone," says Stewart. "We're expanding our group of experts." JUDGE STEWART and family law attorney Robin Yeamans graduated seven years apart from Stanford Law School. Their how-to books on divorce sit side by side in the reference section of the city library. Their rivalry in family court is legendary. "He drove me out of his courtroom," says Yeamans, who believes Stewart resents her strong advocacy for female clients. "It's not personal. I can go in front of Attila the Hun and say 'Thank you, your Honor.' But it's not fair to the client." But beyond the name-calling and hyperbole so common in Family Court, Yeamans argues that Judge Stewart is trying to cause a pendulum swing toward fathers' rights in his courtroom. She says he relies too heavily on the conclusions of a select group of psychologists who share his view and find "characterological impediments" in the psychological profiles of the mothers, particularly those who allege abuses by the father. While unable to cite statistics from Stewart's court, Yeamans believes mothers too often lose custody of their children on Stewart's watch. Stewart returns calls promptly and seems unthreatened by the accusations being raised by Yeamans, other attorneys and the women on the courthouse steps. "My policy usually is not to appoint psychological testing unless there is something specific I need help with, such as a molestation charge," Stewart says. "We don't prove anything with certainty, but a personality profile can give more credibility to one side or the other." Mothers seem to lose most in Stewart's courtroom, Yeamans says, when an allegation of molestation is made against the father. In these cases, forensic psychology is sometimes the only tool to investigate the charge. "I know from 13 years' experience," Stewart says, "that charges of child molestation in the divorce context turn out to be unfounded about 50 percent of the time." In the eyes of Judge Stewart's court, Maria Duncan lost credibility after a psychological evaluation was performed during a contempt of court trial when she failed to make an exchange of her 6-year-old daughter with her ex-husband at a court-prescribed time. During the trial, Duncan alleged her daughter had been molested by an uncle during a visit with the father. Judge Stewart ordered Duncan to be examined by psychologist Terry Johnston to determine if she had any "characterological impairment to sharing the daughter." Johnston recommended that custody be given to the father, who lives in Castro Valley. In determining "the best interests of the child," Family Court first turns to a California law stating that "it is the policy of the state to encourage frequent and continuing contact with both parents." Kathleen Justi lost primary custody of her 7-year-old daughter after Michael Jones testified that she was a candidate for "parental alienation." As in Duncan's case, this was a determination that the mother may hinder future contact with the father. STANDIFER AND Yeamans see the atmosphere in Stewart's court as a subconscious effort to bring new influence to fathers in a system that has historically favored mothers. Indeed, Judge Stewart believes mothers get more than their fair shake with Family Court Services, the last stop before court in disputed custody cases. "In Family Court Services there are so many more women than men, it's embarrassing," he laments. Central to Standifer and Yeaman's theory is that Judge Stewart too often satisfies the "frequent and continuing contact with both parents" requirement of California law by awarding custody to the father, even in cases such as Justi's and Duncan's where the parental bonds seem strongest between the two mothers and their daughters. Justi and Duncan argue they pose no threat to the future relationship between their daughters and ex-husbands. The psychologists saw otherwise, and because they saw a threat, Judge Stewart's best remedy was to give primary custody to the father. "There is not enough emphasis on the parent/child relationship that is commonly the mother," Standifer argues. "It's turned into a parents' rights statement, whereby psychologists are critical of the mother's ability to share the child. Therefore, they remove custody and give it to the father. That's using the child to placate public policy." Sour grapes, says Susan Benett, the opposing attorney in Justi's case. "I find that Stewart is fair and objective. I find his reliance on experts fair and appropriate," Benett says. "It is my opinion that these allegations reflect the anger of unhappy litigants." True, Justi and Duncan are unhappy. "They messed with the wrong mom," says Justi, who vows that she's got the time and energy to continue to fight for change in Family Court. Already the women have formed a Santa Clara County chapter of the National Coalition for Family Justice, a research group that seeks to help people involved in the Family Court process. "They are dedicated," Standifer says. "I think there will be some reform locally in the court in response to their complaints." Reform could involve greater oversight of the system of court-appointed psychological experts that they say is unduly secretive and undemocratic. ON THE DOWNSTAIRS level of the Santa Clara County Family Court, the everyday roller coaster of emotions is almost palpable. Eager couples fill out marriage license forms at a window festooned with fuzzy red hearts, pink streamers and a hanging Cupid. One young couple rifle their pockets to scrape together the $73 license fee. A bulletin board outside the Family Court Clinic instructs the newly divorced to wait for help with child custody issues, visitation and spousal support. Most judges rotate out of family court every two to four years. Boskovich says it's a rare breed of judge and lawyer who can remain unaffected by the vitriol common in family court proceedings. A result of this, Stewart says, is that Family Court is always losing its most experienced judges--a problem because the law becomes increasingly complex. "To some extent, judges need to specialize," he says. "Family Court has always been a place to rotate out of. But what is most bothersome to me is that we have lost our last two capable women judges." But with experience comes familiarity with the people who come to court to do each other harm. Boskovich says this can take a toll on the most ethical jurists. "To sit there day after day and watch people who hate each other and will do anything to hurt each other even if they hurt the children," Boskovich comments, "if you're sitting on the bench and seeing this day in and day out, I think there comes a time when you lose perspective." [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.