![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

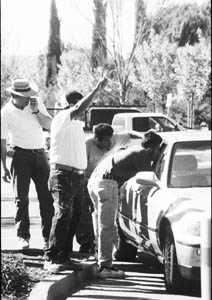

Photographs by Greg Roden Street Smarts: Verbal contracts are standard for day laborers; San Jose's St. Joseph Worker Center would rather the workers go through them to solicit jobs. Streets of Dreams Bush's immigration reform proposal offers undocumented Mexican workers a three-year reprieve. What does this actually mean for the day laborers standing at the corner? By James Espinoza TWO DAYS after Christmas, a group of eager bodies congregated at the corner of Bascom and Downing in San Jose--home to Kelly-Moore paints. These do-it-yourself stores act as magnets for undocumented streets of dreams, since customers who can't quite do-it-themselves are often seeking help at a frugal wage. The morning began like countless others, with a little storytelling to pass the time until a boss in a van or truck picked them up. Sometimes, the stories serve as lessons to newly arrived workers about the dangers of street corner life, like the one about the young man who was solicited outside a Home Depot, only to learn the job involved sexual acts. Other stories reveal the history of these workers' native countries. Fredes, a Salvadoran refugee who fought in his country's gruesome civil war since the age of 14, occasionally entertains the others by reliving the horrific sights and sounds of machine gun fire and bloody corpses. The glazed look in his eyes is a discreet sign he is still looking for an escape from those ammo-smoked Salvadoran jungles. But perhaps it is Ricardo's story that captures a more common experience--an attempt to flee the grasps of poverty and social immobility in Mexico. Back in 1999 in his hometown of Pachuca, Ricardo held a stable job as a steel worker at a Mexican factory. Although this job allowed him to feed some pesos to his starving savings account, the work was dangerous. Ricardo saw workers lose fingers and even an arm. "The company didn't care. Our machines were old and needed to be fixed. They would just stick any piece of metal in the machine and send you back to work," Ricardo recalled. Finally, after a close call of his own, the 22-year-old father of two quit the factory and bought an old taxi as a self-employment venture. His taxi scheme, however, was red-lighted--literally--because of a busted tail light. The endless cost of repairs, along with licenses and fees, which Ricardo describes as "part of the Mexican government's corruption," left him with empty pockets and a receptive ear for rumors about the opportunities found up north. But having grown up without knowing his father, Ricardo feared repeating history by leaving his own children behind, even if it would only be until he could save enough money for their passage. Feeling he had no alternative, Ricardo sold his taxi and obtained an illegal one-way ticket to the United States. With the guidance of a coyote, he crossed the border by walking across the deserts of Sonora and Arizona. Once across, he crammed into a motor home with 53 other immigrants on a less-than-luxury cruise from Arizona to Los Angeles. Unfortunately, the motor home was being tailed by the border patrol. "When we saw that Immigration was right behind us, everybody started yelling for the driver to stop, but the driver panicked. He said this was his first time doing something like this. He freaked out." The rookie smuggler pumped the accelerator, sending the large vehicle into a tailspin. Like marbles in a shaken jar, the frightened passengers slammed into the sides of the motor home and each other. Suddenly, the desperate driver popped his door open and jumped out, abandoning the motor home on its collision path with a gas pipe at a gas station. Luckily, the pipe had just been emptied. "As soon as the motor home crashed, some of us rushed to the door and opened it. We were going to make a run for it. I mean we had already come this far. But as soon as we opened the door, there were about 20 immigration officers with guns pointed right at us." Ricardo and the others were deported, but after a few weeks he managed to cross the deserts again. This time, he successfully reached the Bay Area, where he was ready to stand on a street corner seeking work as a day laborer--a jornalero.

Hidden Faces Every year, an estimated 500,000 undocumented immigrants cross the Mexico/United States border, according to a May 2002 report from the Washington, D.C.-based Migration Policy Institute. The flow of immigrants has refused to decline, despite increased federal spending on border enforcement from $740 million in 1993 to $3.8 billion in 2003. According to a 2002 study from the Cato Institute, the average stay for migrants from Mexico before the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act was 2.6 years; by 1998, the average stay had risen to 6.6 years. The study credits this increase in large part to increased border security, stating, "A U.S. border policy aimed at reducing illegal immigration has perversely encouraged undocumented migrants to stay." The study suggests instituting a circular labor flow, as opposed to permanent migration. This is exactly the idea President Bush has picked up on in his proposed immigration reform. Bush first pitched his reform ideas in a Jan. 7 speech, in which--in a rare effort toward the compassionate part of his self-described compassionate conservatism--he talked about a broken system in which many employers are "turning to the illegal labor market" to fill jobs many Americans are unwilling to take, resulting in "millions of hard-working men and women condemned to fear and insecurity in a massive, undocumented economy." Massive, indeed. It is estimated that in 2000, undocumented immigrants from Mexico alone contributed $220 billion to the U.S. Gross Domestic Product. The Pew Hispanic Center estimates that, in 2001, undocumented workers comprised 58 percent of the workforce in agriculture, 23.8 percent in private household services, 16.6 percent in business services, 9.1 percent in restaurants and 6.4 percent in construction. Furthermore, the taxes paid by undocumented workers--and most do indeed pay taxes, often using fabricated Social Security numbers--"account for a major portion" of the billions of dollars paid into the Social Security system, according to the Social Security Administration. This money can, of course, never be drawn upon by workers who are undocumented; as of July 2002, the Social Security Administration states, these payments totaled $374 billion. According to the Immigration Policy Center, "another frequently overlooked way in which immigrants--undocumented and otherwise--contribute to the U.S. economy is through their purchasing power as consumers." In 2001, the center states, foreign-born immigrants, 26 percent of whom are undocumented, included 5.7 million homeowners holding $1.2 trillion in home value and $876 billion in home equity. In order to bring these undocumented workers "out of the shadows of American life," as Bush stated so dramatically, his plan calls for immigrants, whether abroad or already in the country, to apply for a three-year permit to work in the United States. During the term of the permit, the laborer would participate in American society just like any legal resident--with worker rights, access to certain services and, most important, living without the fear of deportation. The worker would also be able to travel freely between his native country and the United States. Once the three-year permit expires, the worker can either apply for a renewal or return to his or her country. In order to encourage the latter, there would be incentives like tax-savings plans or access to retirement benefits. It isn't clear how Bush's proposal would affect the approximately 9.3 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States with their families--many of whom have already been living here, undocumented, for at least a decade. The Urban Institute estimates that these immigrants are parents to 3 million children who are U.S. citizens and 1.6 million more children who are undocumented. These undocumented families are workers essential to the U.S. economy. They are taxpayers. They are consumers. What would three years of sunlight mean to these shadowed families? Painted Into A Corner On this particular December morning, three years after his successful border crossing, Ricardo was among those standing on the corner of Bascom and Downing. Given the slow economy, he was especially thirsty for work. As a jornalero, one might go days without being solicited. There is nothing resembling job security in this market. Nonetheless, his hopes remained high. Around 7:30 in the morning, a double-cab truck pulled up to Ricardo and two fellow jornaleros, Fredes and Juan. Ricardo recalls that "although the man was Mexican, he only talked in English." "It's an interior job. About six or seven different colors," the potential boss in the truck stated. "How much you pay?" Ricardo, the jornaleros' designated representative, asked in his broken English. "Ten dollars an hour." Ricardo and the man in the truck haggled for a while. One of the attractive factors of day labor is the ability to negotiate the worth of work. In fact, a 1999 study based in Los Angeles by the Center for Comparative Immigration Studies concluded that "day labor work competes favorably, if not better, than other low-skill and immigrant concentrated occupations." The boss finally agreed to pay them at least $14 an hour--a bargain when compared to a traditional painter's wage and the ample experience Ricardo and gang were bringing to the table. As usual, no documents or contracts were signed. Spoken word is law. Ricardo and the other two jornaleros also agreed to use their own tools. This, and the conversation in the truck once the workers were headed to the job site, began to raise red flags for Ricardo that morning. The man who hired them gave his name as Jesse Rios and claimed to have a painting company. But when Ricardo asked him for a business card, Mr. Rios looked around his truck and said he must have left them in his other vehicle. The jornaleros also discovered the house they were going to paint was not in San Jose, but in Modesto, and that the house needed to be painted within three days. The men didn't complain. Work is work, and either way, Mr. Rios promised to drive them home at the end of the day. Once in Modesto, the jornaleros realized this was definitely not going to be a one-day affair. The house was huge. "One of those houses with extra rooms--a house for the rich," describes Ricardo. Still, the three-man crew diligently painted from morning to around 5pm without a break. "We were tired and hungry and even getting dizzy," Ricardo recollects. "With an empty stomach, I swear I was getting sick with the fumes of the paint." Finally the men were granted permission to eat. To their astonishment, Mr. Rios did not offer to pay for their food. For the most part, it is an unstated rule that bosses provide lunch for their streets of dreams. After eating, the three returned to the task at hand. They painted for a few more hours and were then informed they would not be driven back to San Jose. "Mr. Rios said he was too tired to drive us back. We're the ones painting, and he's the one who's tired." The three workers were taken to an empty house to spend the night, only to rise early the next morning to continue painting. By late that afternoon, it had become obvious they wouldn't finish. Mr. Rios, once again, announced that he would not drive them back to San Jose until the painting was complete. Ricardo and the others protested, but Mr. Rios soothed Ricardo with promises of more work and higher pay: "He told me that I was the best worker and that if we pulled this job off there were other jobs lined up. I was able to convince Fredes and Juan to stay when he promised to pay us overtime: Twenty dollars an hour for all the hours we worked past 6." They stayed and painted until 2 in the morning. Not exactly your typical workday.

Paying the Price All that was left the next day were the finishing touches, and the men were eager to get home. "Sometimes those little things seem to last forever," Ricardo says. "But we got done around 4. And not to be arrogant or anything, but the place looked real good." An hour into the drive back to San Jose, the men brought up the subject of compensation. Including overtime pay, they were each expecting $530 in cash. Cash is great for the many jornaleros without bank accounts and simply because these workers live day to day. Cash is likewise lucrative to the bosses for obvious reasons--taxes? What taxes? But instead of the $530, the men were handed another promise. "He told us that he couldn't pay us until the next day. He said he had the big check for the job, but that it was Sunday and the banks were closed. He couldn't cash the check to give us our money." Ricardo, Fredes and Juan reluctantly acknowledged the situation and arranged to meet Rios at the corner of Downing and Bascom at 9am the next day. Ricardo left the truck fairly confident. He had Rios's cell phone number, house number and license plate number. Ricardo knows you can never be too careful. In his wallet sit two business cards of other bosses who never paid him. "I don't know why I keep them," Ricardo says flipping one of the cards and carefully observing it, "but I do." Needless to say, Mr. Rios never showed up the next morning. "And that's not the worst part," Ricardo says with a sense of humor. "You try explaining to your wife--who even filed a missing person's report with the police--that the reason you were gone is because you've been working, and then when she asks you for the money, you don't have it. Now that's a hard one to get out of." Justice: The Real Border Mary Mendez, a program coordinator at the St. Joseph Worker Center in San Jose, a haven for streets of dreams, is not surprised by Ricardo's story. "I hear about these types of cases all the time," Mendez says. "It's a shame. It really is. That is why we try to get workers to solicit jobs in here. At least here they have a guarantee that they will get paid." Established in August of 1993, the center offers a food program, English classes, shower services and, most important, a registration system for the solicitation of work. Mendez advised Ricardo to file a complaint with the state Labor Commission. She also took it upon herself to call Mr. Rios. It has been her experience that sometimes, out of curiosity, bosses will respond to a call from the Worker Center. No such luck this time. Like Ricardo, she was only able to leave a message that has yet to receive a reply. On Jan. 12 of this year, about a week after he sent his paperwork, the state Labor Commission processed Ricardo's complaint--by saying that it was unable to process the complaint because Ricardo did not have Mr. Rios' business address. "I don't get it," says Mary. "A lot of times workers don't even get their boss's names. Ricardo had a phone number and a license plate." Attempts to reach Mr. Rios revealed that his cell phone number was disconnected. This author was, however, able to get in touch with the owner of the Modesto home that Ricardo, Fredes and Juan painted those three days of December. The owner declined to make any comment. Ricardo is not giving up. He tells me that it is not so much about the money anymore. He simply wants to know if any justice can be done when situations like this occur. But assistance is not readily available for workers like Ricardo. After all, he's undocumented and this undocumented status appears to take precedence over his rights. Labor Pains President Bush's proposed three-year worker permit is part of the long tradition of America's attempts to come to terms with immigration. The American market thrives on cheap labor but has absolutely no idea how to make sense of the inevitable social backlash produced by this reality. As Ricardo puts it, "Being the most powerful country in the world, fighting expensive wars in faraway places, how is it that the United States can't control its border? Come on, it's ridiculous. They can stop 'illegal' immigration if they really wanted to, but they just don't want to. What business wants is cheap labor." According to Bush, his plan does bring a certain level of control. But for a day laborer like Ricardo, the plan is far from sweet. One stipulation of the proposed policy is that the applying worker must obtain the sponsorship of an employer who is required to show that the job in question is not wanted by an American citizen. For streets of dreams, who commonly go through as many employers in a span of three weeks as an average American does in a lifetime, this requirement may just be insurmountable. Regardless of this obstacle, Ricardo says, "I would definitely apply. I would apply if it meant the possibility of stable work. That's what us jornaleros ultimately want, consistent work." But when asked if he would return to Mexico after the three years, without taking a breath he responds, "No. How could I return? My kids have been going to school here. My family's life is here now." Herein lies the biggest shortcoming of Bush's plan. It assumes the estimated 9.3 million undocumented people already living in the United States are here as a band-aid for their economic situation in their native countries. The reality seems to be that they are here for a cure. Like the immigrants of America's past, they are here to build a foundation of generational progress. It does not matter what incentive is given to the worker to return. Actually, to some in the Latino community, this whole idea of a temporary worker program brings up unpleasant memories of organized oppression. Beginning in the 1940s, in response to the labor shortage caused by World War II, the United States--in cahoots with the Mexican government--implemented a temporary-worker policy that became known as the Bracero Program. Mexican workers were contracted for certain periods of time and promised certain labor protection and benefits. The plan didn't exactly follow this blueprint. All types of labor abuses occurred: wages were lowered, the braceros were forced to live in crowded living quarters often with no restroom access, and they were even fumigated while working in the fields. The Bracero Program, which even the U.S. Department of Labor officer in charge of the program described as "legalized slavery," finally ended in 1964. José Sandoval, a local community activist who has fought for the rights of the braceros with the Voluntarios de la Comunidad organization, explains, "In many of the bracero contracts that were signed, 10 percent of wages were withheld by bosses to be put in savings accounts, but that money is yet to be seen." The braceros have now resorted to the courts to get their money. This has been a long and difficult process since no agency wants to take full responsibility for the money. Wells Fargo, the bank involved in this ordeal, claims the money was handed over to the Bank of Mexico, and the Mexican government all but admits it has lost the money to corrupt officials. The United States, for its part, says the situation is out of its hands. "Nonsense," Sandoval refutes. "Mexico and the United States need to take responsibility for contracts they signed. In the bracero contracts, the United States clearly states it would protect the workers from exploitation and follow through with the whole program." On Jan. 28, 2003, after years of hearings, the San Francisco courts finally allowed the braceros to sue the United States government. They are currently awaiting a court date. Meanwhile, as the debate over immigration policy will likely heat up in anticipation of an election year, one thing is for certain: undocumented workers like Ricardo will wake up tomorrow morning and stand on the corner of streets like Bascom and Downing. "No matter what," Ricardo says, "things are better here than in many of our native countries. That's what it comes down to." And therefore, in cities and towns throughout the world, many more will be lured to join him.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the April 7-14, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.